A pair of novels from Pier Paolo Pasolini, recently reissued by New York Review Books, display the aesthetic and intellectual range of the Italian writer and filmmaker. The first, his debut, Boys Alive, published in 1955, is a fizzing chemical reaction, its postwar hustler vignettes suffused with speed, lust and disaster. The second, his final work in prose, Theorem (1968), is a chilly, enigmatic parable about a visitor who seduces each member of a bourgeois family and thereby transforms or destroys them. (It began as a poem and was later made into a film of the same name.) Between these two approaches we find tradition distilled and then discarded, moving from gritty Italian neo-realism toward the abstraction of the then-ascendant nouveau roman. Pasolini built upon his literary inheritance before utterly razing it such that neither nostalgia nor mythology could gain a footing. Reading the novels back-to-back is like a cold plunge after a scalding bath.

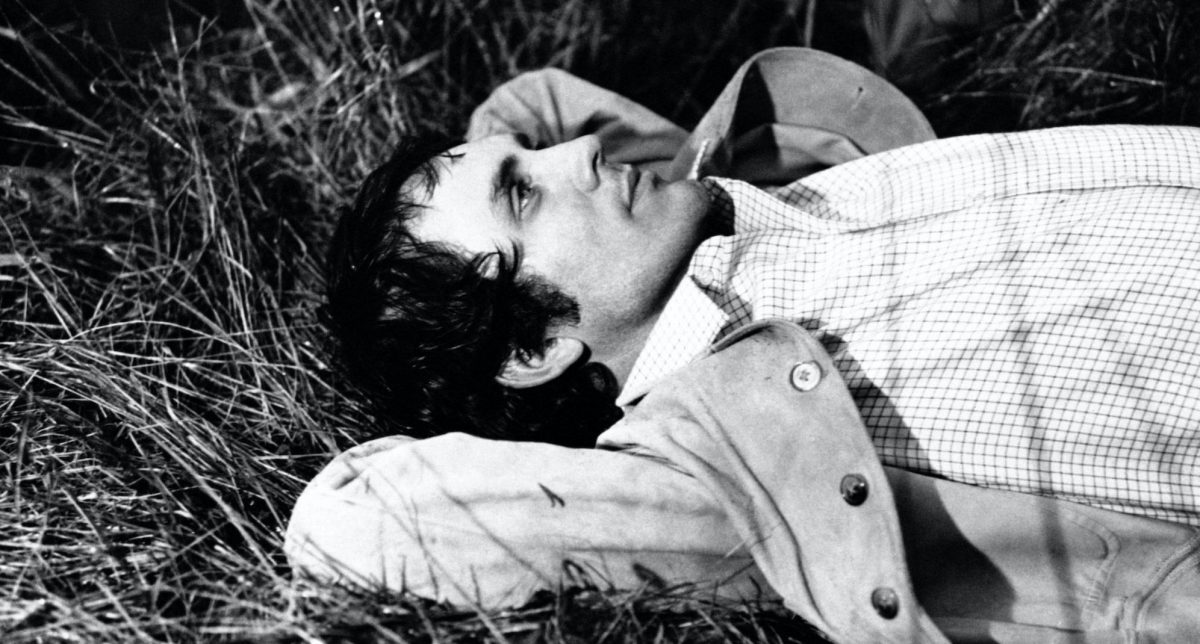

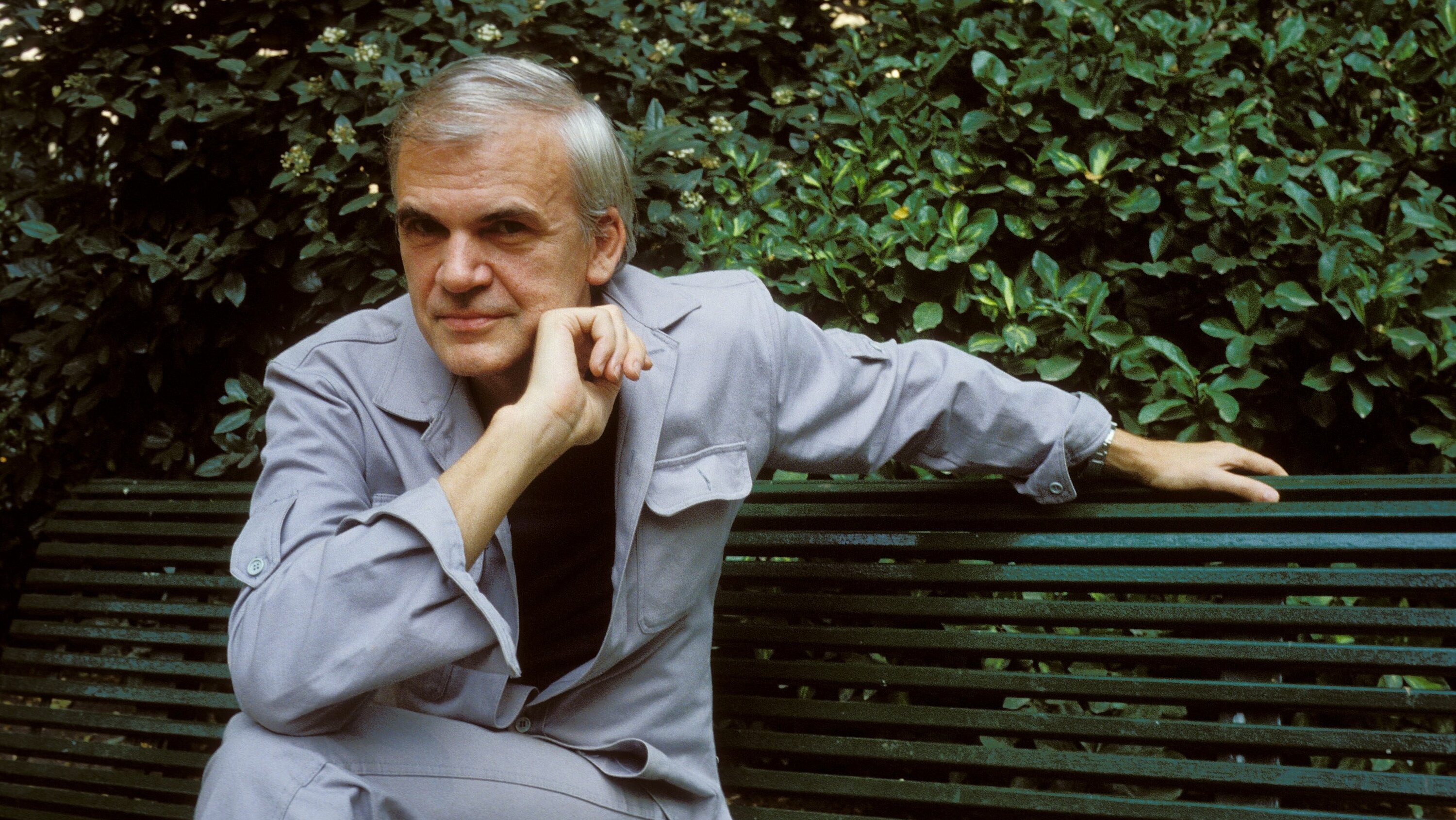

Pasolini was an urban aesthete, conflicted Catholic Marxist, peasant mythologizer and inveterate lech. He was born in Bologna, in 1922, to a Fascist army officer and a schoolteacher. His father’s military postings and sometime imprisonment for gambling debts compelled the family to move frequently. He attended the University of Bologna, writing a thesis on the nineteenth-century poet Giovanni Pascoli. It was there he began to speak openly about his homosexuality. (He was said to have fallen in love with one of the war-ravaged pupils he and his mother taught free of charge.) A series of disasters precipitated his fateful move to Rome. His brother, a partisan, was murdered by rivals in 1945. His father came home from the war in a state of alcoholic paranoia. Then, in 1949, Pasolini was caught with a group of underage boys performing an undisclosed sexual act. The local anti-Communist authorities put him on trial; narrowly avoiding indecency charges, he was nonetheless expelled from the Communist Party and fired from his teaching position. In January, 1950, he and his mother abandoned his father and set out for Rome.

The city was a sea change, a whirl of pleasure, squalor and art. Pasolini’s fall from respectability compelled a reckoning: ‘Like it or not, I was tarred with the brush of Rimbaud . . . or even Oscar Wilde.’ He sought the desperate freedom of disrepute and found it in Rome’s poverty-stricken underclass, particularly in the beautiful, violent young men who furnished him with the material for his early poems and fictions. He stayed afloat via odd jobs: teaching, literary journalism, bit parts in movies. He would later work as a screenwriter for Soldati and Fellini, and go on to direct a variety of disruptive, legacy-defining works including Accatone (1961), Mamma Roma (1962) and Medea (1969). He was murdered, in Ostia, in 1975, likely by a right-wing criminal organization.

Boys Alive remains his best-known novel. It is plotless, headlong, horny, vascular and often unbearably sad. It follows Riccetto and his friends – all the boys have diminutives or nicknames: Trouble, Cheese, Woodpecker and so on – over the course of five years as they pillage, cruise, fight, strut, gamble and narrowly avoid incarceration. Pasolini is unerring in his dramatic instincts. He seeks heat, battle, humiliation, thrilling reversals of fortune. The boys are either skint or flush with ill-gotten spoils. Money is forever being lost and found, then spent recklessly on indulgences. Financial windfalls – from lifting scrap metal, robbing friends and enemies, or sex work – are splurged on fashionable shoes or enormous bar tabs. Riccetto believes ‘cash is the source of all pleasure and all happiness in this filthy world’. It is above all a means of style, to be used solely in service of what the boys call ‘real life’.

What is this ‘real life’ they speak of? Everything pleasurable, everything wanton, everything unpredictable, incongruous and free. It is competition, fashion, swimming, sex, food, drink and indolence. ‘God, I like having fun!’ Cacciota says. The words constitute the group’s personal code, a philosophy with which they reimagine the meagreness of their circumstances. To experience boredom is to have failed ‘real life’. It is to be found wanting, to lose one’s nerve, or else to work a day job, to achieve a shabby respectability. To be short of cash is to lack the shrewdness necessary for living. It is a kind of total defeat. If the alternative to ennui is death, the boys will unfailingly choose the latter. (Many boys die in the novel: illnesses; drownings; car crashes; suicides.)

Weather and youth are the novel’s twin forces of aggression. There is no season but summer and one practically squints while reading, assaulted by page after page of heat and glinting metal. Asphalt yards ‘crackle with flame’, the Colosseum stands ‘burning like a furnace’; ‘rank heat’ rises from a river; bodies sweat under ‘the full blaze of the sun’. It’s nearly impossible to imagine Pasolini’s Rome in winter, so complete is his delirious, fiery dream. The sun is his engine. Its presence suffuses the novel, forever offering up a plausible, heat-addled motive for petty crime or a disorienting backdrop for flashy exhibitionism. It drives the boys, sweating, heedless, into their next misadventure.

The novel’s episodic structure – built loosely around criminal activity, family life, the procurement of prostitutes, group swims at the river, and plenty of shooting the shit – eludes a totalizing narrative. Scenes never outstay their welcome. A climax approaches, your heart lurches or breaks, and then you’re whisked to the next calamity a month or a year hence. It is in these pungent transitions that Pasolini betrays his obsession with cinema, in the way he weds his lyricism to setting, his prose like a camera eye, ever ready for the close up or tracking shot. Translator Tim Parks renders a lean, athletic prose that oscillates between beauty and brutality. Its wattage can’t be overstated. All is kinetic possibility, open-ended, chaotic, alive. No resolution, no hope, only action, action, action.

*

In 1968, Pasolini shot his film, Theorem, in Lombardy. Before it hit screens, he’d published a novel of the same name. Despite some equivocation by contemporary critics, he was quick to dispel any suggestion that the novel was mere film treatment. As translator Stuart Hood notes in his introduction, Pasolini said it was ‘as if the book had been painted with one hand while with the other he was working on a fresco – the film.’ The pleasures and challenges of each work are interrelated, a kind of correspondence. To set one against the other is to ignore this complementary formalism, the way each foregrounds the spiritual corruption and erotic ennui of the bourgeoise.

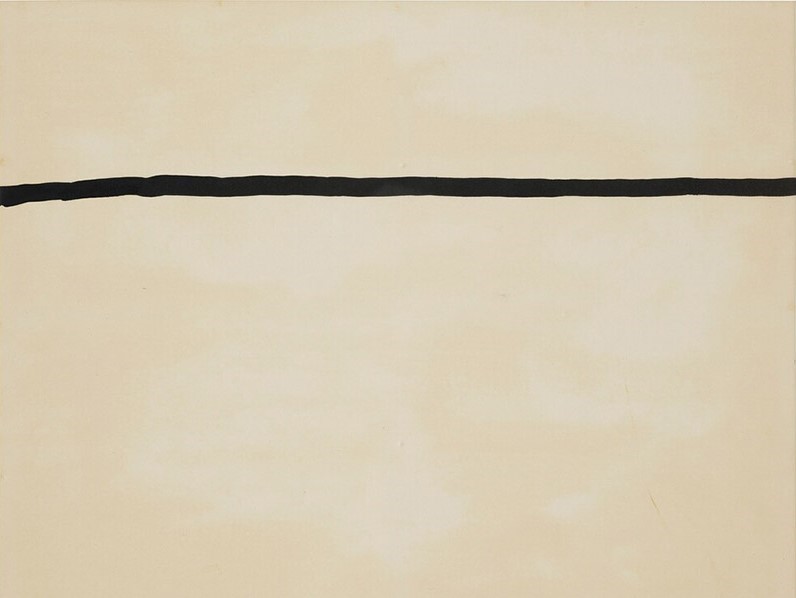

Theorem is a beguiling work of calculated estrangement. Pasolini forecloses any attempt to locate the narrative, geographically or historically. ‘As the reader will already have noticed,’ we are told, ‘this, rather than being a story, is what in the sciences is called “a report”: so it is full of information; therefore, technically, its shape rather being that of “a message”, is that of “a code”.’ Events unfold by way of meticulous description, a kind of poetic data that pins the novel’s subjects like insects beneath glass. What results is an allegory disguised as a memorandum.

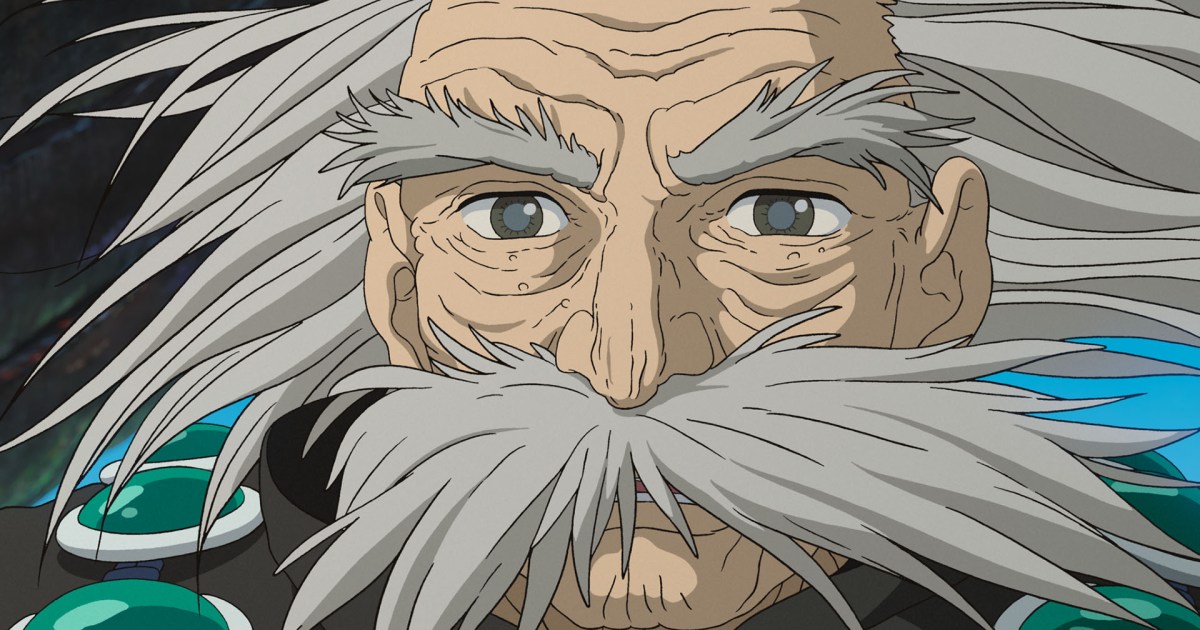

The novel immediately establishes an aura of boredom, drift and atrophy. The family of a well-to-do Milanese businessman endures aimless walks, chaste kisses, drowsy reading, and the ringing of midday bells. This soporific mood is shattered when a beautiful, enigmatic young man invites himself to stay at their suburban mansion. Each member of the family – Paolo, the father; Lucia, the mother; Pietro, the son; Odetta, the daughter; Emilia, the maid – is gradually overcome by the youth. He beds them all, one by one, tenderly, as if the family ‘awoke in him merely a kind of loving compassion, precisely of delicate maternal caring’. His magnetism is effortless, his flesh somehow consoling. He remains an inscrutable presence throughout, a figure of almost biblical ambivalence.

His eventual withdrawal destroys the family: ‘The guest . . . seems to have divided them from each other, leaving each one alone with the pain of loss and a no less painful sense of waiting.’ Each fruitlessly seeks some purpose or diversion to staunch the wound of his abandonment: Emilia leaves her post to float surreally above her village; Odetta becomes catatonic and is admitted to a clinic; Lucia cruises for boys half her age; Pietro becomes an artist, pissing on his work in disgust; Paolo strips at a train station and walks the platforms as if in a dream. Between these descriptive chapters there are lengthy prose poems, ostensibly narrated by a member of the family. Their weighty musings (with titles like ‘Identification of Incest with Reality’ and ‘Loss of Existence’) offer bursts of transgressive interiority. These modal shifts continue through to the novel’s conclusion, ending with a reporter’s staccato questioning of the workers outside Paolo’s factory, a strangely detached examination deploying the ‘kind of language used in daily cultural commerce’. (‘Would the transformation of man into a petty-bourgeois be total?’) This alloy of myth, portent, social commentary and dream was as far as Pasolini could take the novel. From this point on, he would focus solely on filmmaking.

What proof the novel takes aim at – what theorem is being explored – tantalizes in its nearness. It remains an ambiguity swirling beneath the frozen crust of the novel’s surface, luring the reader into a strange, almost empirical participation in the presented facts. Everything trembles with restrained volatility as the family is awoken to itself, its hungers, its failings, the abysses of desire that suddenly open amidst so much ease and comfort. Pasolini is at his best here, a poet of ruinous Eros, of the calamities we welcome and fear, each of us ‘a famished animal writhing in silence’.

Read on: Jessica Boyall, ‘Militant Visions’, NLR–Sidecar.