Jesus of Nazareth lived in a time of political turmoil. Between the lines of the Gospels, which are our main source of information about him, this comes through loud and clear. But it is never brought to the surface. The last thing that the writers of the Gospels wanted was to drag in politics. They wanted to extract Jesus from his real historical situation and put across a universal message, which could apply to anybody. Above all, they did not want to tie Jesus in with the fate of the Jewish people who, at the time of writing, had just been crushed by the Roman legions after a bitter resistance war.

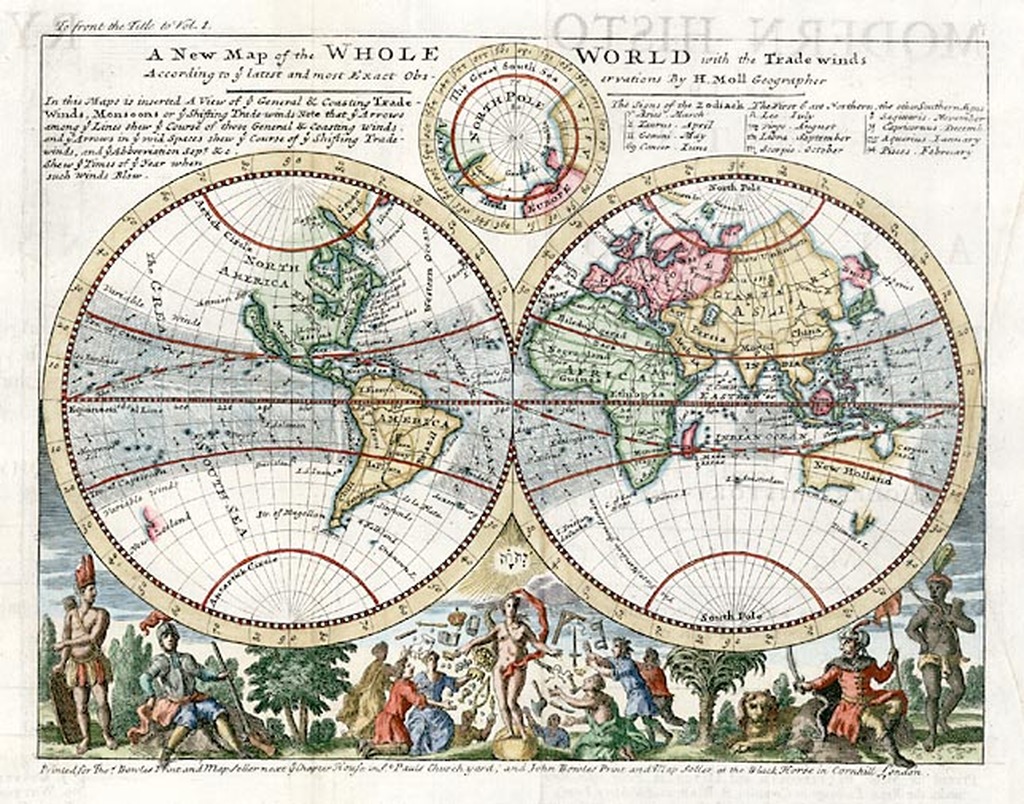

However, the actual situation in which Jesus lived is plain enough. In 63 BC Palestine was conquered by a Roman army, led by Pompey, and made part of the Roman province of Syria. Pompey, accompanied by his military staff, strode into the Holy of Holies of the Jerusalem Temple, which had been defended by its priests after the reigning king had opened the gates of the city to the invaders. From that moment on, until the final showdown 133 years later in 70 AD, the history of Palestine is mainly a history of Jewish resistance to Roman rule. It was a hopeless resistance which took place during a time which fundamentally was one of Roman expansion. Jesus of Nazareth lived right in the middle of this period and, despite his well-known attachment to the other-worldly, he could hardly have been blind to what was going on.

Palestine’s strategic role

The situation was not an easy one for the Romans. Palestine – Judea, as the Jewish part of it was called – was one of a chain of small states, stretching from Armenia down to Egypt, which formed a buffer zone between Rome and the Parthian Empire to the east, based in Persia. Palestine was a crucial link in the chain because it bordered Egypt, granary of Rome. Parthia was the second major power of the region and it was never conquered by Rome. Indeed, it several times inflicted defeats on the Roman legions, routed them and captured the eagles which were their battle standards. So Palestine was a sensitive area. A Jewish uprising could count on Parthian support. Indeed, in 40 BC, only about twenty years after Pompey’s invasion and not very long before the birth of Jesus, this was exactly what happened. The Roman puppet regime was overthrown and a new king installed, with Parthian support. The Parthians, moreover, unlike the Romans, took care not to desecrate the Temple. Their position was more or less like that of the Indians in Bangladesh, a foreign power aiding a national movement for its own purposes.

The Romans reacted quickly. They ditched the old lot of puppets and brought in a new candidate, Herod, who was about 30 at the time. Herod’s father had been the strong man, main pro-Roman in the old regime. Herod himself had been military governor of Galilee, the northern part of Palestine. When the Parthians came in he managed to escape to Egypt and eventually got to Rome. There he was crowned king of Judea. With full Roman backing he returned, taking Jerusalem with the help of the legions in 37 BC, and promptly executed the rebel leaders. The anti-Roman king, Antigonus, was crucified, the first of tens of thousands who were to be executed in this way by the Romans or their puppets. Once on the throne, Herod stuck to it until his death in 4 BC.

It is not certain exactly when Jesus was born. All we can say is that it was during the reign of the Emperor Augustus, who died in 14 AD, and that during Jesus’ adult life Augustus’ successor Tiberius was on the throne. Jesus may have seen the end of Herod’s reign, as an infant. Certainly the events which followed Herod’s death must have impressed him, either as childhood memories or as stories which were told him as he grew up.

Herod’s death

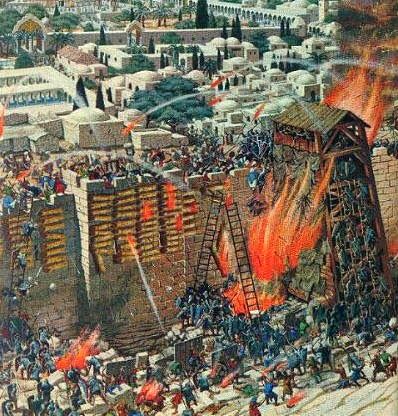

Herod’s death produced a crisis. Herod had been servile to the Romans and cruel and extortionate to his own people. He was loathed and hated. Naturally, when he died there was general rejoicing and the national movement came to the surface again. There had already been rumblings shortly before the end of his reign. A student demonstration, more or less led by two Pharisees, Judas and Matthias, had culminated in the tearing down of the Roman eagle which Herod had displayed in the Temple to please his masters. The ringleaders were burned alive. When Herod finally died, there was an uprising in Jerusalem. The procurator, Sabinus, the top Roman official in Palestine, immediately moved troops into the capital to maintain law and order and also to seize Herod’s treasury. During the festival of Pentecost, fighting broke out between pilgrims to the Temple and these Roman troops. Sabinus was pinned down in the garrison.

At the same time, there was another armed uprising in Galilee, led by a partisan leader called Judas, known as the Galilean, whose father had been executed by Herod for insurgency. This was a large-scale uprising in which the partisans took Herod’s palace in Sepphoris and seized the arms which were stored there. Sepphoris was only a few miles from Nazareth, where Jesus spent his childhood. About an hour’s walk away, in fact. The Romans had to send two legions, that is, twelve thousand troops, down from Syria to suppress these revolts and rescue Sabinus. During the fighting the Temple was badly damaged and Sepphoris was completely destroyed. When the Romans had restored order they crucified 2,000 rebels.

Twice the size of Northern Ireland

Palestine is a comparatively small country. Herod’s kingdom of Judea was not much bigger than Wales, about twice the size of Northern Ireland. It did not extend so far south as Israel does today but it covered a fringe of what is now Syria and Jordan. The population, about five million probably, was not homogenously Jewish. The Jews were concentrated in the Jerusalem area – Judea proper – and in Galilee, to the north, where they were fairly recent settlers. In between was Samaria, where the Samaritans lived. The Samaritans had their own religion which was a variant of Judaism. For example, they did not recognise the Temple, but had their own holy place on a mountain in Samaria. In the towns there were a number of Greeks and Hellenized Syrians or Phoenicians, who had first come in the wake of Alexander’s armies and now identified with the Romans. Herod had encouraged further immigration of Greeks and had built a number of new towns for them, including a new port and capital, Caesarea, which nationalistic and pious Jews would not live in because it was dominated by irreligious monuments, such as a theatre and a racetrack.

The divided country, split by national and religious differences, had some of the features of Northern Ireland or Cyprus. The Jewish national movement took a religious form; it was religion which bound the nation together. The leaders of the Zealots, as the guerrilla partisans were known, were often ultra-religious and religion was one of the two main issues around which opposition to the Roman occupation crystallised. There were riots over the pagan eagle desecrating the Temple, as described above: later, after the Romans had adopted direct rule, there were more riots under Pontius Pilate over the same issue. There were uprisings in the late thirties, only a few years after the crucifixion of Jesus, when Emperor Caligula wanted to put up a statue of himself in the Temple. Ten years after that there was a big riot when a Roman soldier on guard on a roof overlooking the Temple made an obscene gesture to the pilgrims.

Imperialist taxes

The second issue was economic: the Roman tax appropriations. Rome did not tax its own citizens but relied on wringing what it could out of subject peoples. The system was laid down officially and then the actual tax-collection was left to private enterprise, on something like a tender basis. Roman troops backed up the tax-collectors. Naturally tax-collectors were regarded as collaborators with the Romans and there were frequent attempts to sabotage the system and boycott it. Quirinius’s census in 6 AD was designed by the Romans to help implement tax-collection and it provoked widespread resistance and armed struggle, which was not subdued for some time, right during the childhood of Jesus. Once again Galilee was a focus of the revolt, but this time there was heavy fighting in the south as well, led by a shepherd called Athronges. Thousands were killed by the Romans during this period.

Direct rule starts

The census was particularly resented because it marked the beginning of direct rule by Rome. The puppet regime was abandoned by the Romans shortly after Herod’s death. His son was exiled after the Procurator was given full powers, in Judea at least. In Galilee and in South-East Syria, the Golan Heights area, two other sons of Herod were allowed to stay on as autonomous rulers. Generally speaking, the Romans changed Procurators quite rapidly. Pontius Pilate, who lasted nine years, from 27 to 36 AD was an exception to the rule. Pilate was intensely hated and this loathing shows through all the Jewish source documents which remain. He was both harsh and corrupt. When he took money from the Temple treasury there were massive demonstrations against him. He suppressed them by putting troops into the crowd in plain-clothes, and with concealed weapons, who suddenly leapt into action at a given signal. In the Gospels, there are references to the killing of Galileans, always troublemakers, and to riots in Jerusalem at the time of Jesus’s death, while the word used to describe the two ‘thieves’ crucified with Jesus is the same generally used to describe guerrillas, rather like ‘bandits’.

The Pharisees and armed struggle

However, the real struggle built up from the forties onwards, culminating in the full-scale national uprising in the sixties. At the same time, the national struggle began to cross-cut with an increasingly overt class struggle. The traditional ruling class in Judea consisted of an interlocking bloc formed by large landowners and the hereditary high-priestly families who controlled the Temple. The Sadducees were members of this bloc. They were challenged as religious authorities by the Pharisees, who were rigourists, organised on a strict entry basis into cells, led by scribes, graduates in theology, but also including elements from artisan and even labouring backgrounds. It was the Pharisees who welded the Jewish nation together into a religious-political force. Many of the Zealot leaders were Pharisees who had decided to move into a phase of armed struggle.

The mass of Zealots however, came from the people, from small towns and villages. This period was one of an overall movement in the countryside towards large estates, throwing small peasants, many of them in debt, off the land. There were a large number of slaves in Judea at the time and these made up part of the guerrilla armies. There was also an increasing number of hired hands, who are often mentioned in parables in the Gospel. The surplus of labour meant that they were usually employed on a casual basis. There was naturally a drift from the country into the towns and an increasing amount of employment in small craft industries.

Jesus and the apostles came from artisan families; Jesus was a carpenter, working with lumber imported from Lebanon and many of the apostles were fishermen, owning their own boats. We know from other sources that the fishing industry was thriving in Galilee at the time and there was investment in pickles for use in exporting fish. Jesus did not come from the masses, who were either living off charity – there was an efficient dole system in operation – or else were day labourers or slaves. Neither, of course, did he come from the priestly caste or from a rich business or land-owning background. He was a petit-bourgeois.

Kidnapping and assassination

The ruling class throughout this period became increasingly compromised with the Romans. It was the Roman Procurator who appointed the High Priest, usually a matter for bribery. In return, the High Priest acted as a Quisling, maintaining law and order in Jerusalem, a sensitive area for Romans, with his own Temple police and handing over troublemakers for trial. Yet at the same time, the Temple and its High Priest were the main symbols of national consciousness. In the end, class feelings came out into the open. Zealots kidnapped a Temple official and, like Tupamaros, held him ransom for the release of political prisoners. Assassination of collaborators was stepped up, until a High Priest was struck down too.

When, in the sixties, resistance gathered momentum, there were particularly troubled economic circumstances. For years extensions to the Temple had provided employment in Jerusalem and these suddenly halted. After riots, the programme was set in motion again in the form of paving the city streets. At the same time, there were complaints that the high-priestly families, who had equipped themselves with armed gangs, were marauding in the countryside extorting ‘tithes’ on which they had no claim. Matters came to a head in 66 AD when, after a huge tax boycott, the Roman Procurator looted the Temple treasury to make up the deficit. There was an immediate Zealot uprising. The Roman’s main force withdrew and the remnant left behind were massacred. One of the first acts of the Zealot regime was to destroy the record of debts – freeing the masses from the grip of moneylenders and landlords. A new High Priest was elected by lot, which fell to a peasant, an impoverished member of the priestly caste, an act regarded as outrageous by ruling class opinion.

The left is isolated

During the four years between 66 and 70 AD there was all-out war. A whole Roman expeditionary force, comprising two legions and several thousand auxiliaries, was wiped out. The Romans lost over 5,000 infantry and 480 calvary. This victory led to the setting up of a national Government, representing all aspects of religious opinion, both Sadducees and Pharisees, and even Essenes, the monastic group who produced the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Zealots opposed this Government, which they regarded as class-based and potentially collaborationist. They were quite right.

The Jewish commander in Galilee, Josephus, who was a Pharisee, spent more time harassing the Zealots than preparing defences against Rome. When the Romans arrived, under Vespasian, he capitulated on the spot and became an open collaborator. Later he wrote a history of the events to justify his completely treacherous role. The backbone of resistance was led throughout by the Zealots who fought to the last in Jerusalem and then in the mountain fortress at Masada. When the Romans took Jerusalem in 70 AD, under Titus, hundreds of thousands were butchered and the city levelled. Josephus recounts how at one point the Romans ran out of wood for crosses and, when they had enough, had to search for empty spaces to put more crosses up in. It is in this context, that the crucifixion of Jesus and the writing of the Gospels must be seen.

Where did Jesus stand?

It can hardly be believed that he was as oblivious to what was going on around him as the Gospel writers make out. Roman reprisals must have struck the families of Jews known to him in the area. One of Jesus’s own disciples, one of the Twelve, was Simon the Zealot, who presumably participated in one of the uprisings.

Reading the Gospels, the picture presented in the main is that of a passive collaborator. Although Jesus was condemned and executed by Pontius Pilate, every effort is made to clear him of any real responsibility. Crucifixion was not a Jewish method of execution. It was the Roman punishment for political crimes. Spartacus was crucified, for instance. Whereas the Jews had responsibility for ordinary crimes and for religious offences, the political crimes went to Pilate. Yet the Gospels claim that Pilate washed his hands of the affair, protested Jesus’s innocence, could see no wrong in him and was only pressured into crucifying him by the High Priest and his lobby.

Jesus himself is represented in a pro-Roman light. For example, he is described as friendly with tax-collectors and collaborationists. He heals the child of a Roman centurion. He advises, not simply going along with the authority of Rome under duress, but going twice as far as required. And, of course, the most important incident recounted concerns the payment of tax. ‘Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s and unto God that which is God’s’. In the Gospels, this is presented as a particularly cunning reply which outwitted the Pharisees who asked it. In fact, it is not at all equivocal. It plainly supports the payment of taxes to Rome. The whole question of taxation was the burning issue of the day. On this issue, Jesus took a pro-Roman stand and backed the claims of the Imperial power.

Keeping Jesus clear of Judaism

The counterpart of this pro-Roman attitude of the Gospels is the persistent denigration of the Pharisees. The Zealots, as such, play no part in the Gospel story at all. They are simply suppressed verbally, as the Romans suppressed them militarily. But the Pharisees are very much in the forefront. They are used as straw-men who feed Jesus the straight lines which enable him to score off them. The purpose of this, as far as the Gospels are concerned, is clearly to distinguish Jesus and the Christian community from the Jews and the Jewish cause. In almost every case, it is a disagreement with Judaism which is stressed, so that Jesus can be distanced from his own people. Stories like that of the Good Samaritan are heavily promoted to the same end.

A number of scholars have tried to rescue Jesus from this Pro-Roman presentation, especially in recent years when, after Auschwitz and Belsen, commentators on the Gospel have at long last become sensitive to its anti-Jewish bias. In particular, the episode of Jesus’s trial has been gone over in detail and it has been admitted that Rome and not the High Priest was responsible for his execution – as a political offender.

Pilate was not a weak administrator who was likely to allow the High Priest’s lobby to pressure him against his better judgement.

Pacifist sentiment

This line of reasoning has led some writers to go as far as claiming that Jesus was actually pro-Zealot and sympathetic to armed struggle. This interpretation means discounting the great slabs of pacifist sentiment which fill the Gospels as nothing but post-Fall of Jerusalem PR, put in by the fawning Evangelists, eager not to rub Rome the wrong way. In contrast, episodes like driving the money-changers out of the Temple are stressed and the fact that Jesus was arrested by an armed patrol and one of his disciples drew his sword and resisted arrest. Indeed, Luke describes how Jesus apparently instructed his disciples to buy swords just before the arrest, though he quickly adds that two would be enough.

It is certainly true that there are patches of anti-Roman material in the Gospels which may get closer to the attitude of Jesus, or at least the early followers, than the Gospel writers do. For example, the story of the Gadarene swine seems to have an anti-imperialist gibe hidden away in it. Jesus exorcises an evil demon, who is called ‘Legion’, and the demon then enters a herd of pigs who plunge over a cliff. The Roman occupation troops were known as ‘pigs’ by the Jews, so the moral is pretty clear. But conversely, there is a definite strain of anti-Temple feeling in a Jesus’s preaching. He is critical of a number of Temple institutions, particularly the financial institutions, and more than once criticises the various ways the Temple made money: donations, taxes, commercial transactions and so forth.

Above all Jesus did not in any way advocate violent resistance to the Romans, but believed that it was necessary to undergo a spiritual change in readiness for the coming of the Kingdom. He conceived of this change in a way which brought him up against the Pharisees, because he was an anti-traditionalist in his attitude to the Jewish religious Law. Ethically, he was a purist, but not in a legalistic way. Judging from his numerous parables about vineyards, labourers and husbandmen, he was fully satisfied with the existing relations of production, including slavery, and the general economic set-up, though he was distrustful of the rich. He seems to have felt that the Temple should not be in any way a secular institution, either commercially or politically.

Jesus not subversive

In itself, there was little that was subversive in Jesus’s preaching and, in this sense the Gospel writers were right to portray him as a passive collaborator. But his fate was sealed when he began to attract crowds, partly because of his feats of healing, partly because he was a compelling orator. The Gospels several times tell how he tried to get away from the crowds and give them the slip, anxious about the outcome, as well he might be.

Pontius Pilate’s last official act for example, in 36 AD, only two or three years after Jesus’s execution, was to massacre a crowd of Samaritans who expected a revelation on their Holy Mountain. Anybody who gathered large crowds was in danger of being halted in their tracks for political reasons. In Rome the careers of sports and theatre stars were abruptly stopped when they began to acquire supporters who were too vocal or demonstrative.

Religions of the oppressed

It is quite usual for messianic and prophetic religious movements to spring up in times of political upheaval. Jesus can be compared with the new movements which sprang up as part of the response to the advance of European imperialism: Peyotism and Ghost-dancing among the American Indians, Ringatū among the Maoris, Hòa Hảo in Vietnam. These movements attempt to break out of the confines of an apparently hopeless historical predicament, by stressing a glorious other-worldly role for the followers of their prophet. In a time of political turmoil, they appear dangerous to the authorities, anxious to suppress anything which might develop into a threat, usually cynical and ignorant, and inclined to err on the side of ruthlessness rather than mercy. They are put down and, if the circumstances are right, a new cult based on the prestige of martyrdom springs up.

The man in the middle

The real strength of Jesus’s preaching lay in his ability to respond to conflict without being sucked into it. He was the man in the middle. Not only was he in the middle of a class conflict but of a national liberation struggle. He was able to find something to say which made sense to all kinds of people without ever coming down on one side or the other. This still is his strength. The discontented, the disaffected, the wretched of the earth could respond to him. So could tax-collectors and Roman soldiers. In part, this was because he chose out of preference to speak in riddles and parables, to tell stories rather than make statements. But partly too it was because he had a talent for the ring of truth, for words which sounded right, which pushed everyone a little bit further together. He walked a verbal tightrope which he wove as he went along. And he could back it up with a quotation every time. It is precisely because he had this ability to reconcile conflicting aspirations, that he sometimes seemed subversive. But in the long run anything that covers over contradictions by appealing to both sides always favours those in power, and Christianity still does.

First published in the left weekly 7 Days, 22 December 1971. An offshoot of Black Dwarf, the paper ran from October 1971 to March 1971; it is available at the Amiel Melburn Trust internet archive under Creative Commons license.