I first heard about the work of the American writer Susan Taubes on a date. I mentioned that I wanted to write a novel that resisted fragmentation – one that would sustain a scene or an idea or a thought over several pages, several thousand words, in the flow of unbroken narrative. My date wasn’t impressed. The novel is such an expansive form, he replied, why would you want to write in such a conventional way? Because I admire it, I said. This proved persuasive and laid the matter to rest. We saw each other only once more after that, and then (to my dismay) never again. A few weeks later, I bought a copy of Divorcing, which he had said exemplified the possibilities of the form.

Possibility, indeed. Divorcing was the only novel Taubes published in her lifetime, and was recently reissued to great acclaim. This was followed by a previously unpublished novella, Lament of Julia, collected with nine short stories. The word, of course, has two connotations. There’s the possibility of shimmering potential, and the possibility of a set of prospective options, which remains suppositional until one is realised. Taubes’s life story lends itself to the first. Born in Budapest in 1928, she emigrated to the United States before the outbreak of war, completed a doctorate on Simone Weil, taught religion at Columbia, married and had children. Shortly after Divorcing appeared in 1969, she drowned herself off the coast of East Hampton, at the age of 41. The novel had been dismissed a few days earlier in the New York Times by Hugh Kenner; Susan Sontag expressed a belief that her friend’s suicide had been linked to the review.

It is the second sense of possibility that better characterises her fiction. ‘Her life cannot be told’, says the narrator of Lament for Julia. It is a remark that could serve as an axiom of Taubes’s work. The novella begins with the disappearance of Julia, conveyed in lyrical soliloquy. Time and setting are unspecified, though the work shifts from a fable-like account of her childhood to a more realist adultery plot. The only daughter of Mother and Father Klopps, as a child Julia sucks her thumb, wets the bed and daydreams. In adulthood, she marries and has children. She appears to lead a generally contented life but the narrator intimates that only a sense of propriety is keeping Julia in the marriage. Eventually, she falls passionately for a younger man and begins an affair. By the end, Julia has absconded – where to, we do not know. The narrator is bereft: ‘She must’ve slipped away; while I was talking, I didn’t notice; I went on talking to myself. And now it is too late. I have lost her. Lost Julia’s beauty in the water’.

But Lament for Julia is not as straightforward as a synopsis might suggest. We never discover who – or what – the narrator is. ‘If she were simply a body and I simply a mind. If only it were as simple as that. But we are a jumble of odd bits and between us we do not even make up a person’. Is it Julia’s conscience, or a demented guardian angel? The narrator – and we as readers – spend the novel struggling to grasp the nature of their relationship. ‘How did I come by her? What had we to do with each other?’ Despite apparent sorrow at losing Julia in the end, the narrator is deeply ambivalent about her, and their ontological dependency: ‘She was my constant nagging pain. My shame and despair. I wanted to get rid of Julia. But what was I without her?’

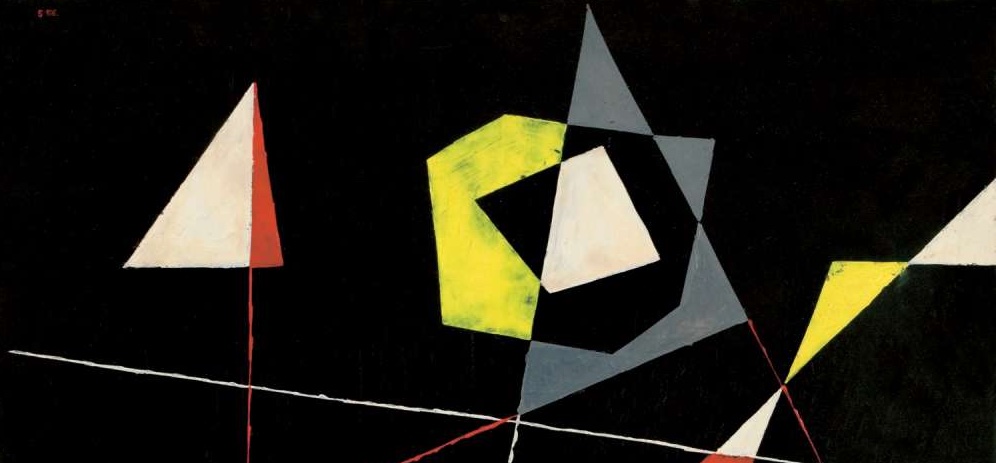

The account offered of Julia’s life is equally plagued by indeterminacy. Attempting to describe the Klopps home, for instance, the narrator wonders how it should do so, finding its memory comprised of ‘impressions with as little logical connection as in a dream’, ‘the various facets and angles’ of the house ultimately failing to ‘make up a consistent object’. Julia remains similarly elusive: ‘My sense of her is less of a person than of things, places and seasons’, the narrator confesses. The details, it seems, are unfixed: ‘Shall I not give her a better girlhood? . . . When Julia was still with me I could revise her life at a moment’s notice’. There are said to be many possible and apparently conflicting ways to portray her – child, wife, adultress and so on – though the narrator admits that there ‘could only be one canvas’. ‘Painted by several hands’, it concedes, ‘But which was the true one? Were they all true?’ Lament for Julia is ultimately less an account of Julia’s life than of the narrator’s struggle – and ultimate failure – to narrate it.

If Lament for Julia is an exercise in absence, Divorcing is an experiment in abundance. It narrates the life of Sophie Blind, whose biography overlaps with Taubes’s own. The novel opens with her death – she is run over by a taxi in Paris – and then turns back to her life: her divorce from her belittling and pompous husband Ezra; her relationship with a lover named Ivan; her life as a child in Hungary, with a philandering mother who remarries a younger man and a psychoanalyst father who takes her away to live in the United States. We follow these different threads of a life through fragments composed in a multitude of different styles, tenses and perspectives. The first of four sections alone flits from narrating Sophie’s life in the third person to assuming her own voice in the first once she realises that she is dead, before moving into a letter possibly addressed to her lover, from the present to the past.

Running through these shifts, implicitly and explicitly, is Sophie’s own inability to explain herself, to make sense of her life. Attempting to end her marriage, she notes that she cannot explain to Ezra why it is over. ‘Must it be explained?’ she wonders. ‘Even if her own position is groundless, the fact is she has no position, has no plans, she is nowhere.’ At times, Sophie seems less unable to explain herself than unwilling to, resistant to sense-making: ‘Thinking about the sense of one’s life, trying to make sense of it, was an idle and useless preoccupation, Sophie had always believed. Worse than useless, it was positively unhealthy. In short, a bad habit.’ The novel itself is devoid of order and sense in the conventional meanings of those words, caught as it is between life and dreams and death.

Near its end, the narrative returns to Sophie’s childhood: ‘The double loss of a world and of the person who belonged to that world was experienced by an anonymous schoolgirl in a sailor-blouse uniform and high brown laced shoes. Sophie Landsmann, the name on the trolley pass, who was she?’ By this point the reader has spent over two hundred pages considering Sophie’s life, too many for her to be referred to with an indefinite article or her full name. The passage is disorienting, even disconcerting, and reads like a possible beginning. It may well be the case that Taubes intends to disorient the reader; it is also possible that the effect arises from artistic indecision. Why choose how to begin a story, when all the possible beginnings could be included?

But then, why choose to begin a story at all? Sophie herself is apparently writing a book, but when asked by her father to explain what kind of book it is, she refuses to answer. Writing for her, unlike psychoanalysis for her father, is not about ‘coming into consciousness’. The purpose of writing, for Sophie, is the certainty of the final product:

A book is simply and always a book . . . With a book, whether you’re reading it or writing it, you are awake. The question does not pose itself. Writing a book appealed to Sophie on all these grounds. In a book she knew where she was. Because, however baffling and blundering and ambiguous, a book was a book.

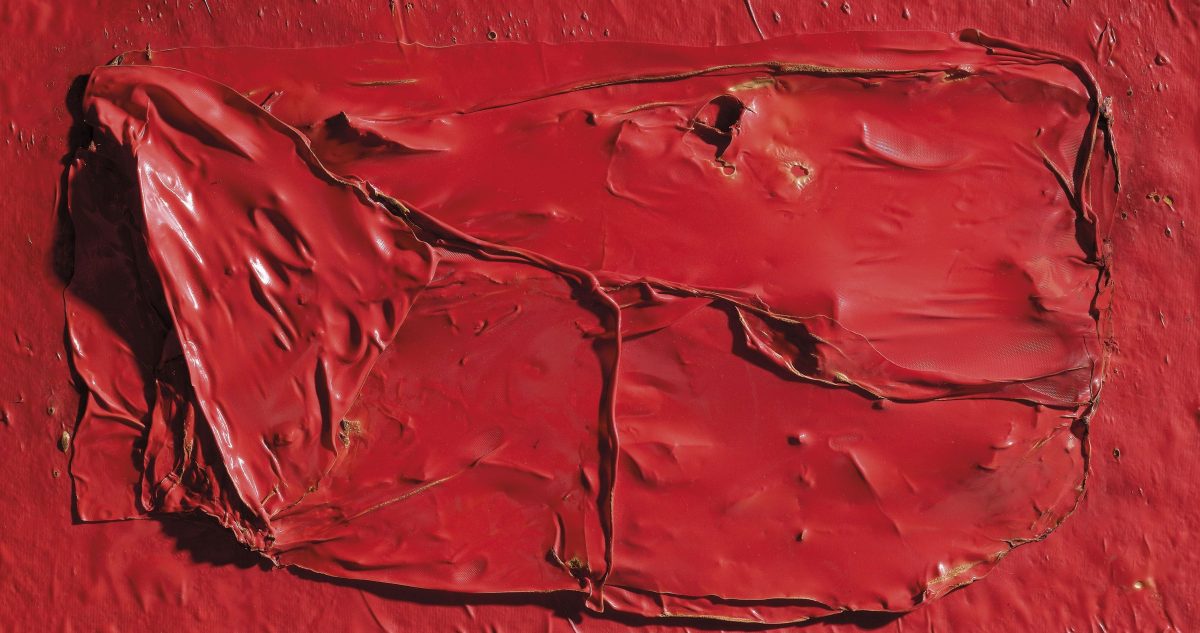

These lines seem to justify a ‘baffling and blundering’ book, absolving the writer of responsibility and acceding to the failure Taubes depicts. Her narratives are less accounts of their protagonists’ lives than of their failures – failures that begin with an inability to express who they are, how they feel and what they want. Sophie appears incapable of articulating her feelings: ‘There was something she had to tell him . . . She could not tell him . . . she could not speak at all.’ Her only act of self-assertion is a negative one: her refusal to answer her father’s question about what kind of book it is, perhaps because she herself doesn’t know, or can’t say. Divorcing mirrors this inability to speak in its refusal to cohere, to assert or resolve itself aesthetically. Taubes’s novels feel as if they break off mid-sentence, still seeking a form for failure that wouldn’t itself succumb to it. Formally and thematically, they are works of unrealised possibilities, and ultimately of limitation.

Assessing her work in the London Review of Books, Jordan Kisner writes that to ‘know where you are, to be able to name things and feel that you belong among them, to come home to oneself in language – this is what Taubes strives towards but can’t fully achieve. Her writing never moves in a single direction, never resolves itself. This isn’t an aesthetic failure, but it is existentially painful.’ This is perhaps the closest any contemporary writer on Taubes comes to acknowledging the failure of her work. That no one has, and that Kisner stops short, speaks to a collective inability (perhaps refusal) to recognise the deep tragedy of her work – and her death, too.

Read on: Claudio Magris, ‘The Novel as Cryptogram’, NLR 95.