Who is Arthur Rambo? To hear the name spoken, it is the young radical poet who comes to mind. To see it written conjures instead the image of Sylvester Stallone’s muscle-bound action hero. The disturbing ability to be both, for one individual to contain two apparently opposed personalities, is at the heart of Laurent Cantet’s new film, released in French cinemas this month. When we meet Arthur Rambo, he does not go by that name anymore. He is Karim D., the new star of Paris’s literary scene. A second-generation Algerian immigrant, he has just published a first novel about his mother’s courageous journey from le pays to begin a new life in France which has ‘stunned’ the critics and set the Twittersphere alight with praise. ‘Your story is my story Karim’, ‘Thank you Karim D. You have given me a voice to speak about my own past’ are among the types of comments posted after the young writer delivers yet another charming television interview. The opening shot of the film shows him seated in a studio against a green screen special-effects background. Framed in deception, in other words, is how Cantet introduces us to his protagonist, in an elegant foreshadowing of what will follow.

For the next fifteen minutes or so we are with Karim as he navigates the crowds, dressed in a sharp tie-less suit, the man of the moment, a smug grin fixed on his face. He is at a party at an upscale venue in Paris. The setting is a high-rise, not of the suburban social housing we will later enter as we step back into Karim’s childhood, but in a neighbourhood that through the huge windows looks like La Défense, the financial district. This is 21st century French publishing: the smoky cafés of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, historically the backdrop for anything associated with the capital’s literary scene on screen, are nowhere to be seen. At this gathering people are talking business. After discussing a film adaptation of his novel with one producer, Karim weaves his way through the trays of canapés and champagne and into a room where strobe lighting illuminates a gyrating crowd. He joins in, taking centre stage, then steps out for a breather on a balcony, the lights of the city behind him.

Enter Arthur Rambo. Someone online has made the connection between Karim and the tweets he posted under this pseudonym a few years before. In an instant all Rambo’s old tweets are shared. As Karim scrolls on his phone, we read what he is seeing, one message after the other. Their vehemence, their vitriol, their crude anti-Semitism and misogyny, is stomach-churning. ‘You have destroyed all my faith’, ‘That’s what happens when you let the suburbs come into the centre’… are the tone of the reaction tweets starting to flow. Karim’s downfall is as quick and as definitive as the drop of the guillotine’s blade. Commentators on the left denounce him as an embarrassment and a fraud, those on the right as a perfect example of what they have always said about the racaille, or scum, of the banlieue.

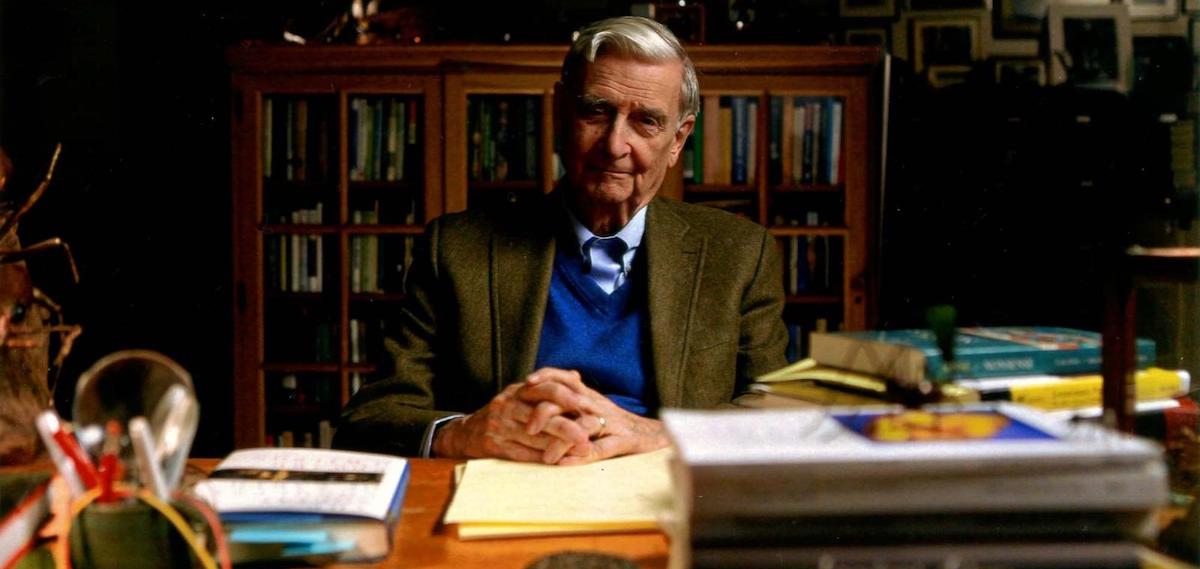

This is the ninth feature by Laurent Cantet, one of France’s most interesting and understated directors. Born in 1961, he grew up living in a school in a small town in the Deux-Sèvres region of central France where his parents worked as teachers. His introduction to cinema came through a ciné club they organised for pupils, as well as watching classics on television. He initially studied photography in Marseilles but, he has said, soon grew impatient to tell stories and in 1983 enrolled at the prestigious IDHEC, since renamed La Fémis, where many of France’s directors are educated. During his studies he formed a close-knit group with other budding filmmakers in his class – Dominik Moll, Gilles Marchand, Robert Campillo – and their friendship has been integral to his work since then, leading to several collaborations on various features. In the 1990s, as he began to shoot his own films, he also joined the collective ‘Les cinéastes des sans-papiers’, an activist group calling for the legalisation of undocumented workers and he has contributed shorts for all their portmanteau films to date: Nous, sans-papiers de France (1997), Laissez-les grandir ici! (2007), On bosse ici! On vit ici! On reste ici! (2010) and Les 18 du 57, Boulevard de Strasbourg (2014).

Cantet’s dominant themes have been clear ever since his first short Tous à la manif in 1997. There he focused on students organizing a protest, and one young man hoping to join them, but held back by family loyalties and his role as a waiter in the bistro where they are gathered. Class dynamics, social issues of various kinds, and the tensions between personal loyalties and political beliefs are the substance of Cantet’s cinema, and this – in addition to a more traditional approach to mise-en-scène – has set him apart from those more typically celebrated as France’s leading auteurs, both domestically and internationally, such as Claire Denis, Léos Carax and Gaspar Noé. More provocative and formally experimental, but less occupied by ordinary lives and struggles, these directors tend to steal the limelight at festivals and have garnered more critical and scholarly attention.

Among Cantet’s stand-out features are his second and third films, which focus on the world of work and our relationship to it. The clash between unions and management is at the heart of Ressources humaines (1999), which examines this through the prism of a father-son relationship. L’Emploi du temps (2001), meanwhile, takes loose inspiration from the Jean-Claude Romand affair to follow a man who pretends to go work each day even after he has been fired from his white-collar job. Cantet’s best-known work that won him the Palme d’Or at Cannes, Entre les murs (2008), takes place in the education sector. But while that was familiar territory, he has also worked outside his comfort zone, studying the relations between outsiders and locals in two other key films set in Haiti, Vers le sud (2005), and Cuba, Retour à Ithaca (2014).

The idea for Arthur Rambo derives from the case of Mehdi Meklat. This affair sparked a major controversy in France in 2017 when it was revealed that the 24-year-old Meklat, celebrated for his Libération blog, regular radio appearances and his first novel, had a pseudonym, Marcellin Deschamps, under which he posted racist, misogynist and homophobic tweets. Until then he had been that rare thing in France: an Arab media personality. ‘He allowed himself all excesses’, Meklat would later say to explain why Marcel Duchamp had inspired his pen name. He imagined Deschamps doing the same: ‘How far could he go? What would be his limits?’ For Cantet, Meklat presented an enigma that sparked his imagination, much as the mass murderer Romand had done for L’Emploi du temps. ‘I remember’, Cantet said about his discovery of Meklat, ‘the impossibility to me of superimposing these two images of the same character: the witty and politically irreproachable radio columnist and the author of these messages. It was such an enigma that I began to read more on the subject, and watch the videos’.

In the film, Karim echoes Meklat’s defence of his actions for his Rambo persona – it was all about testing the system’s limits, and should be read as playful, ironic, experimental. Cantet examines this by turning the film into a series of mini-trials. Karim has to answer the challenges that come from different people in his life, from his family and old neighbourhood friends to his media-savvy agent and publisher. Their charges vary from bien pensant outrage to emotional bafflement – ‘I don’t know who you are’, says his tearful girlfriend, a sentiment shared by his mother – as well the impassioned call from his younger brother to never apologise because he and his friends look up to him and understood what he was doing. This argument, made by Farid in a barren room at the top of the high-rise where Karim grew up, is a chilling revelation for the older brother as he sees the younger generation taking him literally, their own frustrations developing into a more extreme form of resistance that he claims he had never intended.

Cantet deals particularly well in Arthur Rambo with the formal challenge of representing social media on screen. Rather than resorting to the more typical clunky shots of someone reading their phone, the camera hovering over their shoulder, Cantet instead presents tweets onscreen like a block of hovering subtitles. ‘I make the tweets part of the drama’, he explained in a recent radio interview, ‘because I believe the text takes on a terrible weight when it is put on the big screen’. The ‘dazzling quality, and the violence of social media at the time. That’s what I wanted to show by putting the tweets on screen in the film and then showing them unfurl so quickly we no longer have time to read them. They enter our thoughts and live like a parasite, with their big slogans and punchlines… which are a reduction of any form of reflection.’

Who is Arthur Rambo? Who is Karim D.? In the end, Cantet does not solve the enigma presented by his anti-hero. Karim sits in the back of a taxi riding along the Paris ring road at night, heading ‘somewhere, just to get out’, as he writes in a text to his girlfriend. Meklat too got away, to Japan, and then returned a year later to publish Autopsie (2018), an essay in which he sought to explain his actions. This uncertainty, driving into the night with nowhere to go, seems the only ending possible to Cantet’s story. The enigma of Meklat and the fractures his actions exposed remain unresolved – he never apologised, and what he represented both before and after the revelations are still a source of discomfort and debate. That Cantet stayed true to this ambiguity is characteristic of his strength as a director, and it may also explain why the reception of Arthur Rambo in France has been strikingly muted. Meklat offered no closure to what he brought to the surface, and Cantet too resists any false resolution on screen.

Read on: Stathis Kouvelakis, ‘The French Insurgency’, NLR 116/117.