The historian Arno Mayer recently died at the age of 97. His career began with a book scrutinizing ten months of diplomacy during the First World War. It ended with a pair that ranged from ancient Greece to modern Israel. It’s not unusual for scholars to start small and finish big. But Mayer’s was no journey from narrowness and caution to largeness and risk. From the get-go, he took on the deepest questions and widest concerns, finding a vastness in the tiniest detail. Political Origins of the New Diplomacy (1959) discovered in the fine print of the months of diplomacy from March 1917 to January 1918 how the Russian revolution transformed the war aims of the contending powers, leading to Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points and inspiring ‘the parties of movement’ to act against ‘the parties of order’. The follow-up, Politics and Diplomacy of Peacemaking: Containment and Counterrevolution at Versailles (1967), which covered, again, roughly ten months, this time from 1918 to 1919, charted a reverse movement: the triumph of right over left.

But something did change for Mayer over that half-century of writing history. He discovered the bookend truths of Jacob Burckhardt and W.E.B. Du Bois – that you can never begin a work of history at the beginning and can never bring it to a satisfactory end. You’re always in between. Mayer liked to attribute his in-betweenness to being born Jewish in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The child of a marginal people in a marginal country, Mayer was repelled by nationalism and drawn to cosmopolitanism like those other great historians of Europe from small countries: Pirenne (Belgium), Huizinga (the Netherlands) and Burckhardt (Switzerland). That inheritance led him to diplomatic history, a world in between states. Mayer told this origin story so often – and the story has so often been told – that I’ve come to think of it as the equivalent of a family myth. I see his in-betweenness differently.

I was introduced to Arno as an undergraduate at Princeton by my roommate, the son of the European intellectual historian Stuart Hughes. I don’t know if it was my personality or my connection to Hughes, but for whatever reason, Arno immediately made me feel like family. His writing gives the impression of an old-world Jewish sophisticate, but in his being and bearing, he reminded me of nothing so much as my very non-academic Jewish American family from the suburbs of New York. Arno always asked about parents, children, and grandparents first, before he talked politics or scholarship. He was affectionate, demonstrative, warm. His feelings were as strong as his opinions were sharp. He had passion and presence. He loved to gossip and plot, especially at academic conferences. He kvelled, he complained, he was stocky and short.

That was Arno. That was also his work. If it was in-between, it was not because he hewed to or hailed from the margins. It was because Arno, by disposition and temperament, was always trying to get inside, to get to the centre of things, to connect across the perimeter. Other diplomatic historians studied the relations between states. Arno looked inside of states, at the domestic relations and power struggles within. When he wrote about the French and Russian Revolutions, he turned not to Marx or Lenin but to The Oresteia and the Hebrew Bible, master texts of familial violence and personal vengeance. Where other Marxist historians of the twentieth century spoke of the transition to finance capital and the corporate form, Arno was more impressed by the staying power of the family firm.

His most daring and enduring ideas – that the First and Second World Wars were like the Thirty Years War of the seventeenth century; that the history of modern Europe is not one of a rising bourgeoisie but of a regnant aristocracy; that the Holocaust might be compared to the pogroms of the Crusades, a work of detoured ambition, in which a marauding army from the West, crazed and stymied in its quest for the lands of the East, acts out its zeal and frustration on the helpless Jews caught in the way – are not the creations of a contrarian. They are reflections of a spirit seeking to dispel the depersonalizing aura and bureaucratic myths of modernity in favour of more intimate, domestic, familial, and lineal, but no less tractable or terrible, examples from the past.

Those and other ideas once made Arno the most heterodox of Marxists, a practitioner of what he called social history from above. Today, they read like dispatches from the daily news. Take his most important work, The Persistence of the Old Regime (1981). From the moment of its publication, specialists challenged Mayer’s claim that the landed interests of the European nobility, including Britain’s, remained economically and politically hegemonic up through the First World War. Despite those challenges, the book, well, persists. It contains multiple provocations that have come to seem only more pertinent with time.

In his analysis of Europe’s states and empires, particularly their political structures and institutions, Mayer drew inspiration from Engels’s famous claim, in Anti-Dühring, that as early modern Europe came to be ‘more and more bourgeois…the political order remained feudal’. We might take similar instruction from Mayer (and Engels) today. The United States has one of the most archaic constitutional orders of the world, designed originally to protect the interests of the landed, monied, and enslaving classes, the white and the wealthy, from the majority. Not only does that constitutional order still, today, protect and enhance, through the state, older, whiter, more conservative, and more privileged sectors of society. It also is almost completely impervious to the forces and demands of demographic and social change, particularly young people, people of colour and newer immigrants. Of all the constitutions in the world, the American is the most difficult to amend. While scholars and journalists lavish attention on the social dysfunction of America – the racist and other pathologies of the white working class, the refusal of evangelicals to accept truth and facts, the toxic influence of television and social media – they pay less attention to what Schumpeter called the ‘steel frame’ of the political order. That was Mayer’s great theme: the archaic holdover of the social and economic past, how it takes shape and form in the state and its institutions, inviting reactionary, elite but declining, forces to find refuge, succour, position and space. It should be our own.

Nor can the family capitalism discussed in The Persistence of the Old Regime be treated as a European holdover of a feudal past. Thanks to the work of Thomas Piketty, Steve Fraser and Melinda Cooper, we now see family or dynastic capitalism as a fixture of our neoliberal present, a deliberate recreation of a form that was supposed to have been destroyed by two world wars and replaced by the multinational corporations and investment banks of the global economy. Imagined in different ways by Mises, Hayek, and Schumpeter – scions of that fading central European imperium that Mayer continuously anatomized in his work – dynastic capitalism is the product of elite political moves and countermoves that Mayer thought were intrinsic to all forms of capitalism. Political capitalism, in his telling, is the only kind of capitalism.

Where we imagine today’s city as the home of the left, The Persistence of the Old Regime reminds us that the city can be the natural space of the right. At the turn of the last century, European cities, particularly imperial capitals, employed vast numbers in the tertiary sector of commerce, finance, real estate, government and the professions. Members of those sectors, which included much of what we today would call the PMC, often outnumbered the more traditionally recognized ranks of the urban proletariat. Far from generating a cosmopolitan or metropolitan left, they were a breeding ground of the radical right.

Until recently, Mayer’s political geography of the city might have seemed of historical interest only. With Israel’s war on Gaza, it bears re-reading. An alliance has emerged, or simply become visible, in metropolitan centres across America – of wealthy donors from tech, finance and real estate, and their underlings; government officials; university administrators and employees; philanthropists; cultural movers and shakers; local politicians from both parties; and pro-Israel politicos and campus groups – exercising increasing sway over urban spaces of culture and education. These are not the obvious forces of Trumpist reaction – the small business owners or independent car dealerships that leftists have emphasized or the white working class that liberals love to hate. Indeed, many of these individuals contribute to the Democrats and voted for Biden. But they are Mayer’s prototypical sources of reaction, claiming the mantle of victimhood as they enhance the imperial projects of some of the most powerful nations on earth. And they may help put Trump back into office.

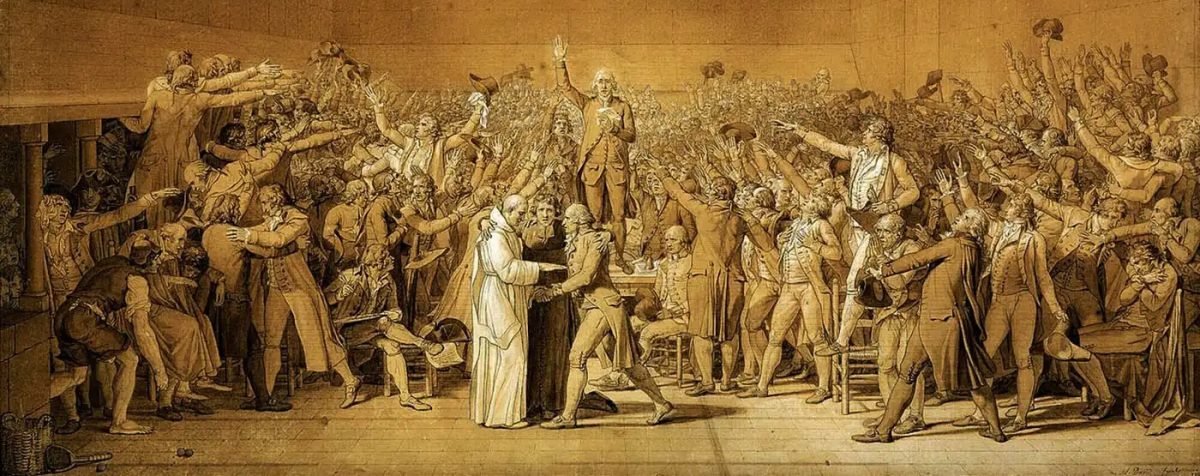

Perhaps Mayer’s most proleptic – and, not coincidently, least discussed – idea is that of vengeance. It emerged late in Mayer’s career, I think, in his work The Furies (2000). Seeking to counter the revisionist consensus on the French and Russian Revolutions, which held that ideological utopianism fuelled their descent into violence and terror, Mayer claimed that each side of the struggle, the revolution and the counterrevolution, was inspired by a desire for vengeance, to retaliate against longstanding injuries and more recent acts of violence. While the revolutionary side sought to impose what Michelet called a ‘violence to end violence’, to create a new form of sovereignty that would stop the wilding in the streets and bloodshed in the countryside, it soon discovered what Clytemnestra and Orestes realize in The Oresteia: every attempt at one final act of violence only sets the stage for the next.

For years, I read Mayer’s account of vengeance as merely an attempt to salvage utopian thinking from the dead hand of the Cold War. More recently, I’ve come to think of it as an uncanny description of what was to come, of what solidarity and animosity look like after the Age of Ideology or the Age of Revolution or the Age of Utopia has come to an end. Every day, on the internet or in the streets, people are called upon to avenge an act taken against themselves or their team. Every day, a new litany of historical injuries is amassed to explain the previous day’s excess. Every day, a history of mutual loyalty or diffident trust is dissolved to make way for the next day’s excess. No conflict is resolved; no congress is achieved; no constitution is drawn. It is fury without end.

Arno dedicated his life to opposing that world, to finding coherence amid chaos, to extracting a story from sound, to identifying the path forward for the party of movement. That he failed, in the end, to do so, that he wound up reverting to the most ancient texts to explain our most modern predicaments, is a sad and sobering thought. Yet his example may still offer us a way forward. Sartre said that ‘a victory described in detail is indistinguishable from a defeat’. It would be foolish to think that we could simply reverse the predicates and proceed to victory from there. Perhaps we might try a different tack. Might not a defeat described in detail offer the left something akin to what Rosh Hashanah offers the Jews? Not a chance to begin – Burckhardt (not to mention the rabbis) warned against that delusion – but a chance to begin again.

Read on: Perry Anderson, ‘The Figures of Descent’, NLR I/61.