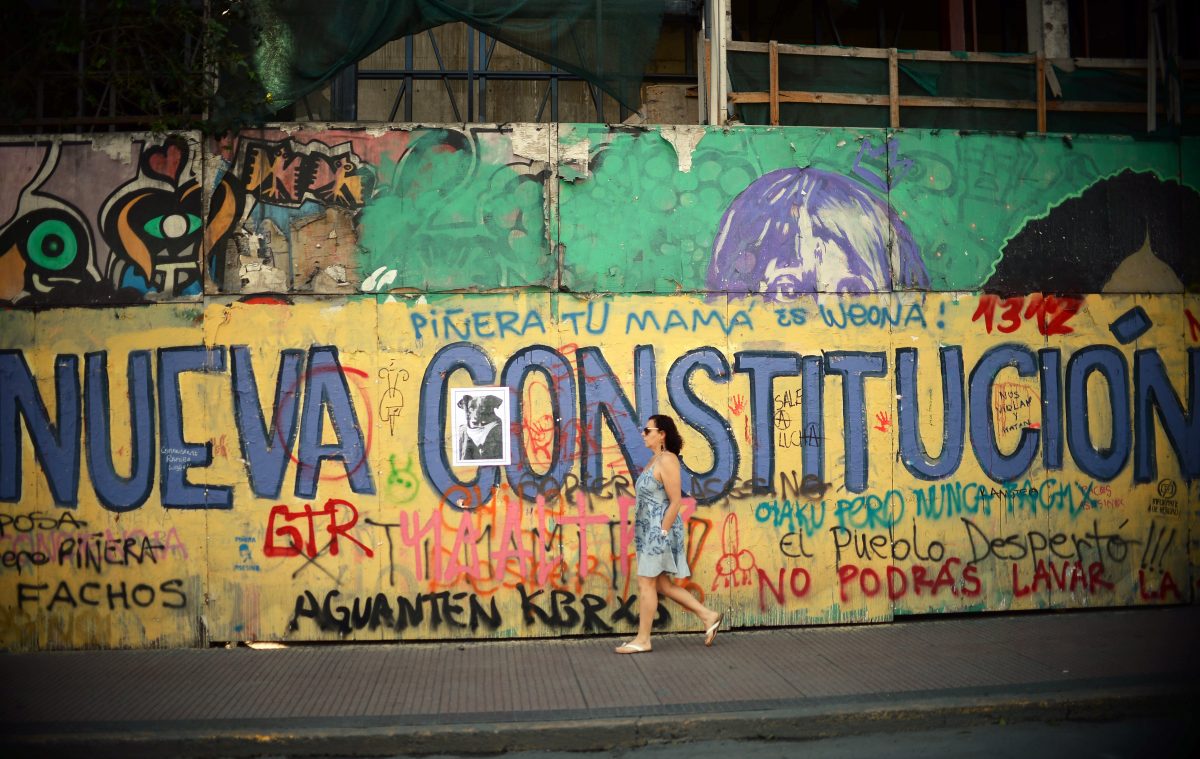

‘Meddle: to involve oneself in a matter without right or invitation; interfere officiously and unwantedly’, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary informs us. The term ‘meddling’ belongs to that category of words that – like novel strains of viruses – strike seasonally, only to disappear with equal mystery. Now that the American political system has undergone an unprecedented crisis of legitimacy under the refrain of rigging, with Donald Trump instigating a riot (however tragicomic and folkloric) in the hallowed ‘temple of democracy’, nobody seems to remember that the delegitimization of the American electoral system began four and a half years ago with this word, meddling. It was with the accusation of meddling that, for the first time since the Second World War, one of the parties tried to discredit the outcome of the ballot box. A lot of water had passed under the bridge since 2000, when the Democratic candidate Al Gore accepted without a word the legal coup carried out by the US Supreme Court (instigated by Justice Antonin Scalia), who refused to recount the contested votes in Florida.

By 2016, the situation had changed: it was not an ongoing process that was contested, but an outcome sanctioned and ratified by the Electoral College. With the election lost, the aim was to invalidate the victory of the opponent in the name of foreign interference. From 2016 to 2019 the word meddling dominated US political life, sparked an FBI investigation, provoked the dismissal of one of its directors (James Comey), created the figure of Special Counsel Investigator (Robert Mueller), and monopolized entire congressional sessions.

But last November, when the losers were no longer the Democrats but the Republicans, the meddlers magically disappeared, replaced by riggers. If Trump was accused of winning thanks to the meddling of a foreign power, the newly-elected Biden is charged by his defeated rival with fraud – with cooking the books, so to speak. This time, the election had been rigged.

In both cases, the common and unprecedented feature is the recourse to conspiracy. Usually, it is the losers who turn to planetary conspiracies – the Trilateral Commission, the Bilderberg Group, the pluto-Jewish-Masonic plot – to explain their subalternity. In the United States, however, we are witnessing a new phenomenon: the two pillars of the establishment – which have governed the greatest world power for centuries – are themselves resorting to conspiracy theories, with all the self-victimization that this entails.

In a sense, the rigging wielded by the Republicans in 2020 was a riposte to the meddling launched by the Democrats in 2016. The crisis of American representative democracy manifests itself thus: a set of mutual accusations, each consonant with the political temperament of the respective injured party. It is therefore worth investigating the history and background of meddling to understand the nature of the crisis of representation that we are witnessing. The mentality of Cold War liberals seems to echo in the charge of interference levelled at Russia in the wake of 2016. So brazen was the intrigue that it was almost as if, at one point, it was possible to confuse reality with scenes from the 1962 film The Manchurian Candidate, where a would-be presidential nominee is exposed as a Soviet double agent. Given Washington’s century-long record in the sport, the idea the United States could accuse another power of meddling in its own elections was laughable, at least to those of us neither American nor Russian. Recalling the shameless interference staged by the Americans during the 1996 elections in the former Soviet Union is more than enough to provoke a sense of irony. As Peter Beinart wrote in The Atlantic:

Yeltsin’s ‘shock-therapy’ economic reforms had reduced the government’s safety net, and produced a spike in unemployment and inflation. Between 1990 and 1994, the average life expectancy among Russian men had dropped by an astonishing six years. When Yeltsin began his reelection campaign in January 1996, his approval rating stood at 6 percent… So the Clinton administration sprang into action. It lobbied the International Monetary Fund to give Russia a $10 billion loan, some of which Yeltsin distributed to woo voters. Upon arriving in a given city, he often announced, ‘My pockets are full.’ Three American political consultants – including Richard Dresner, a veteran of Clinton’s campaigns in Arkansas – went to work on Yeltsin’s reelection bid. Every week, Dresner sent the White House the Yeltsin campaign’s internal polling… It worked. In a stunning turnaround, Yeltsin – who had begun the campaign in last place – defeated his communist rival in the election’s final round by 13 percentage points. Talbott declared that ‘a number of international observers have judged this to be a free and fair election.’ But Michael Meadowcroft, a Brit who led the election-observer team of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, later claimed there had been widespread voter fraud, which he had been pressured not to expose. In Chechnya, which international observers believe contained fewer than 500,000 adults, one million people voted, and Yeltsin – despite prosecuting a brutal war in the region – won exactly 70 percent.

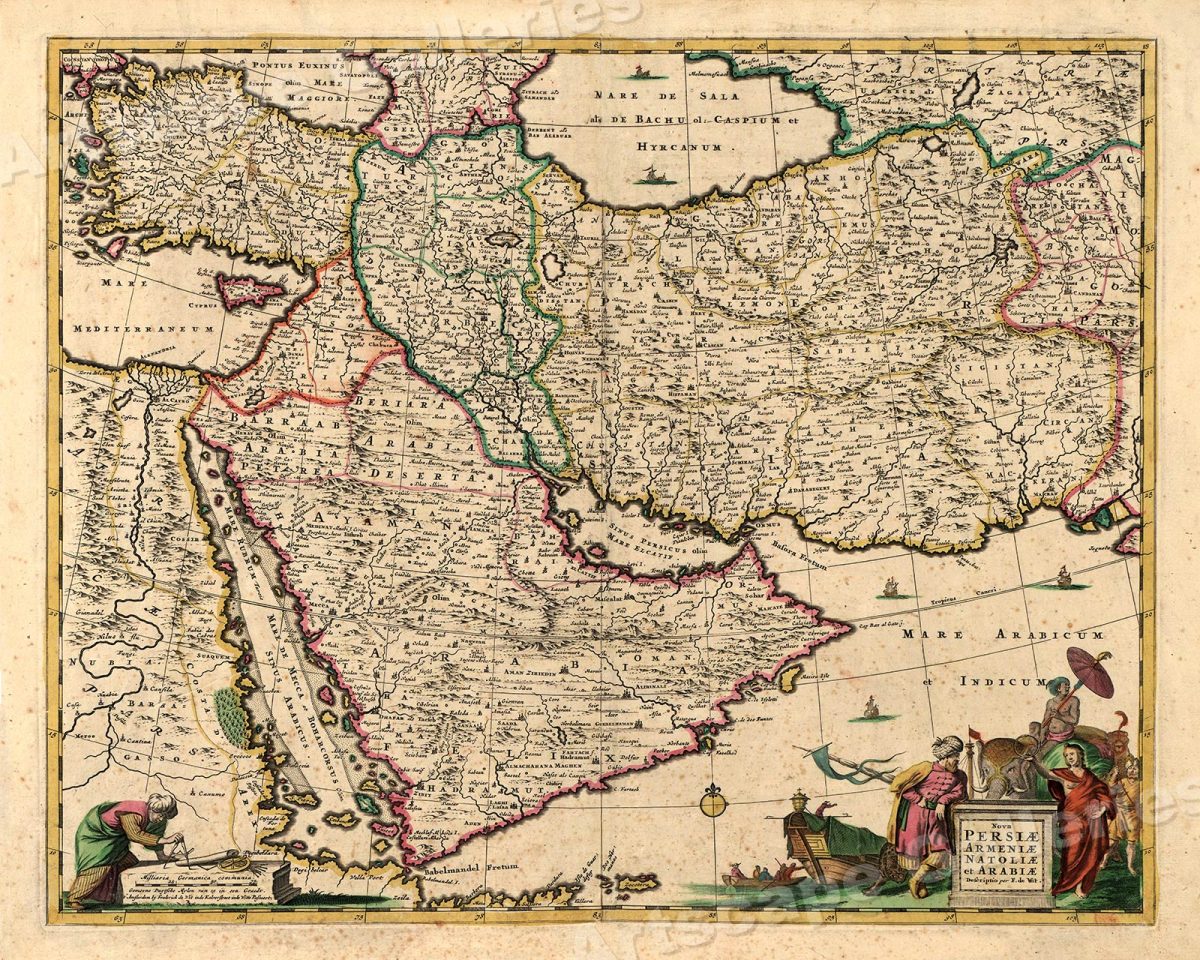

This obviously wasn’t the first case of election meddling carried out by the United States, nor would it be the last. Professor Dov Levin of Mellon University has indexed 62 American interventions in foreign elections between 1946 and 1989. Meddling often took on forms that exceeded mere monetary incentives; the figure omits, for instance, various coups organized in the infamous banana republics thanks to lobbying from the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita Brands International): from Honduran president-elect Miguel Dávila’s deposition in 1912, to the overthrow of the democratically elected president of Guatemala Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán in 1954. Far from exceptional, the CIA’s ousting of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 for having the audacity to nationalise Iran’s petroleum industry was a textbook procedure. After the Cold War, particularly memorable was the helping hand offered to Haiti in 1994 to finally rid itself of president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a former priest and advocate of liberation theology; the support given in 2003 to Georgia’s Rose Revolution, which deposed president Shevardnadze (an old Soviet notable) and replaced him with pro-NATO former Minister of Justice Mikheil Saakashvili, and the backing of the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine with funding explicitly reserved for ‘independent media, non-partisan political education and training for independent observers’. Support was offered anew for the Euromaidan protests of 2013–14, when Senator McCain visited Ukraine to dine with exponents of the far-right, whilst Victoria Nuland, the Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, distributed sweets among the protesters in Independence Square before selecting her preferred candidates for the future government with the sitting American ambassador.

Excluding instances in which interference amounted to coups d’état or assassinations, it would be misguided, if not wrong, to be excessively shocked by this list. After all, what is foreign policy if not interference in the affairs of other states that aims to create favourable conditions for one’s own interests?

To be sure, there are various styles of foreign policy. It can proceed covertly, doing its best to advance undetected. But it often has no qualms banging its shoes on the table (as Khrushchev did very literally during a meeting of the United Nations General Assembly in 1960). However practiced, it has always aimed to empower certain factions at the expense of others: in kingdoms of old, the trick was to secure succession to the throne for the branch of the ruling family most closely related to one’s own dynasty (such that in the 18th century inheritance of the crown became a recurrent casus belli, triggering conflicts appropriately named ‘wars of succession’). Where, on the other hand, power was assigned by vote, the strategy of intervening in others’ elections enjoys an equally eventful history.

The Hellenist Daniella Ambrosino notes how in the ancient Greek poleis, for instance, one could find

the institution of proxenia: citizens chosen officially by foreign cities as local representatives of their interests. These pròxenoi would go to great lengths to ensure that decisions taken by the city would be the most favourable for their clients. The exploits of Cimon, pròxenos of Sparta, who strove to maintain peaceful relations between Athens and Sparta during the Persian Wars, are well known. Given the chance Greek cities would interfere – continuously, and by any possible means – in the matters of other poleis. Every effort would be made to make a city revolt against democracy, or, conversely, to pit the populace against the ruling oligarchs. It was hoped that regime change would compromise alliances; in 447 BC Thebes instigated a highly successful oligarch revolt opposed to the democracies of Chaeronea and Orchomenos, Boeotian allies of Athens. Persian schemes were also customary; Xenophon tells us of satrap Pharnabazus who, in order to deflect an attack from the Spartan king Agesilaus, sent Timocrates of Rhodes to distribute ten thousand gold drachmae among Greece’s largest cities to persuade them to renege their obligations toward Sparta. The emissary toured Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos, convincing substantial factions in each city to pursue anti-Spartan policies.

Before concluding this digression, we must not forget the great invention of the 20th century: the so-called ‘humanitarian intervention’ of liberal democracies, in whose name interference is not just practiced, but paraded as a virtue.

When viewed as part of this long lineage, Russian electoral meddling is of pure-bred pedigree. It comes as no surprise that the Russians, Chinese or Israelis would try and meddle with elections whose result determines their domestic political life. Maybe the question to ask is why more instances of interference have not been exposed with similar diligence. Israel and Saudi Arabia may have had an equal (if not larger) stake in Trump’s election than Russia. In fact, one of the Trump campaign’s biggest donors over the years has been the late Sheldon Anderson, the billionaire Las Vegas casino owner who was married to the owner of Israel’s most circulated free daily Israel Hayom (nicknamed ‘Bibiton’, a portmanteau of Netanyahu’s nickname and the Hebrew word for newspaper). And what of Mohammed bin Salman, whose destiny seems interwoven with that of the Trump family, most especially with the fortunes of the factotum son-in-law Kushner?

And then there is the issue of the efficacy of the interference. That the Russians had every intention to influence the US elections (as the US does repeatedly around the world) is beyond doubt. But that their attempts would prove successful was always quite improbable. American election campaigns now cost billions of dollars; in 2016 the total cost was $6.5 billion; $2.4 billion for the presidency and $4 billion for Congress; in 2020 the total cost rose to the staggering amount of $14 billion, of which $6.6 billion was for the presidential campaign.

Based on hearings carried out by Congress, Russia spent no more than a few dozen million dollars in its efforts to influence the 2016 elections, an amount which we are led to believe was more effective than the billion and change spent by Clinton. Moreover, the disparity between the two countries clarifies the absurdity of the whole matter. When I ask how Russia’s GDP compares to that of Italy, Germany or America I’m often met with an embarrassed silence. The answer I’m not given is that Russian GDP amounts to three quarters that of Italy, a third of Germany’s and one thirteenth of the US. If it is conceivable that the United States successfully meddles in Italian political life, the idea that Italy might shape the course of American politics in its own interests is hardly credible.

Thus, we must take it for granted that foreign powers pathologically seek to interfere with the selection of other countries’ rulers. But we can be equally certain that these attempts have very little chance of succeeding, especially when it is the weaker who interfere with the stronger. So, from this standpoint the meddling affair tells another story: namely that for two electoral cycles the losing party in the US elections has tried to delegitimize the other’s victory, appealing to the discourse of meddling or rigging. These attempts at subversion indicate that a transfer of power between the two parties no longer represents the rotation of members of a ruling class belonging to a single, dominant social bloc, as was the case during the entirety of the post-war period.

In fact, we tend to forget that in representative systems, electoral contests can maintain the character of a sporting competition – clear winners, fair play, an inviolable sense of ‘political etiquette’ – only if they do not directly endanger the interests of the contenders. The fact that the parties of the American political duopoly have each begun to delegitimize each other’s victories indicates that the interests of the social blocs they represent are diverging to the point of becoming irreconcilable. We have two images of this rift. The first is visual: the pictures of major US cities being garrisoned by armed troops and armoured cars to ‘guarantee’ the inauguration of a new presidency: images we thought were reserved for third world countries before or after a coup. The second image of this rift is lexical. For there’s a difference between interference and meddling. ‘Meddling’ evokes a covert, underhand suggestion altogether absent from ‘interference’. Whilst Webster defines meddling strictly in terms of interference, the Oxford English Dictionary reveals an additional connotation: ‘Meddle: mix, mingle, combine; mix (goods) fraudulently; having sexual intercourse (with)’. Unsurprising, perhaps, for a strategy that aims below the belt.

Translated by Francesco Anselmetti.

Read on: Mike Davis on the 2020 election.