‘Tulips’, borrowed from Sylvia Plath’s poem, is the title of a recent series of work by the British artist duo Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings. On view at Tate Britain until 7 May, the series consists of six, two-by-two-metre fresco paintings mounted on five-centimetre-thick wooden panels, accompanied by a graphite drawing on paper that bears the title of the series. Paying homage to Italian Renaissance masters such as Masaccio and Uccello, these works explore power dynamics and structures in modern societies.

Quinlan and Hastings began their artistic partnership around 2014, a year after they graduated from Goldsmiths College in London. Their first collaboration involved building gay bars in studios and holding live events to critique male-dominated sex culture. Using a Go-Pro camera, they spent nine months filming interior spaces of more than one hundred gay clubs across the UK, documenting their closures as a result of austerity, and at the same time recording a transition to hybrid forms of queer spaces. In 2016, the moving images they had assembled were condensed into a five-and-a-half-hour moving image archive titled UK Gay Bar Directory.

Quinlan and Hastings’s work combines contemporary practices such as filming, installation and performance with traditional techniques including wall rubbing, drawing, etching and egg tempera painting. Through drawing, they developed a passion for Italian Renaissance art. Their figures tend to be muscular and androgynous, offspring of those created by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Their strategy of deconstructing power by re-presenting it bore fruit in a series of twelve etchings, which became the centrepiece of a joint solo exhibition in 2021 titled Disgrace: Feminism and the Political Right. The prints, created with hard-ground etching and aquatint, map out a timeline of right-wing feminism, starting with Imperial Ladies Auxiliary, which depicts women’s complicity in the construction of Empire since the Edwardian era, and concluding with I’m Not a Woman I’m a Conservative and We Will Not Be Silenced, which challenge the ‘Women2Win’ rhetoric and trans-exclusionary views in today’s politics.

Their enthusiasm for Renaissance paintings and interest in critically examining public spaces led to their latest experiment: fresco painting. Fresco as an ancient technique developed in an intimate relationship to architecture. It usually involves painting with water-based pigments directly onto wet lime plaster spread over a wall surface. Because of the strict requirements of drying time – the painting must be completed while the plaster is wet – a fresco is painted section by section in what is called a giornata (a day’s work). Once dry, the pigment absorbed by the plaster, the painting becomes an intrinsic component of the walls of the building. With a monumental style, historical frescoes often carried the function of illustrating the moral codes of a society. The six paintings on show at the Tate derive inspiration from frescoes at the Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The main portions of the chapel were painted by Masolino and Masaccio in the 1420s and the rest was completed by Filippino Lippi sixty years later. The narrative centres on Saint Peter, re-establishing the authority of the Church and the primacy of the Roman Pontiff, both of which had been under threat since the Great Occidental Schism of 1378. In these compositions, the physical appearance of the figures corresponds to their moral status. Saints are usually depicted as standing with both feet firmly positioned on the ground. Solidity of posture conveys spiritual gravity. Good and evil are discernible at a glance.

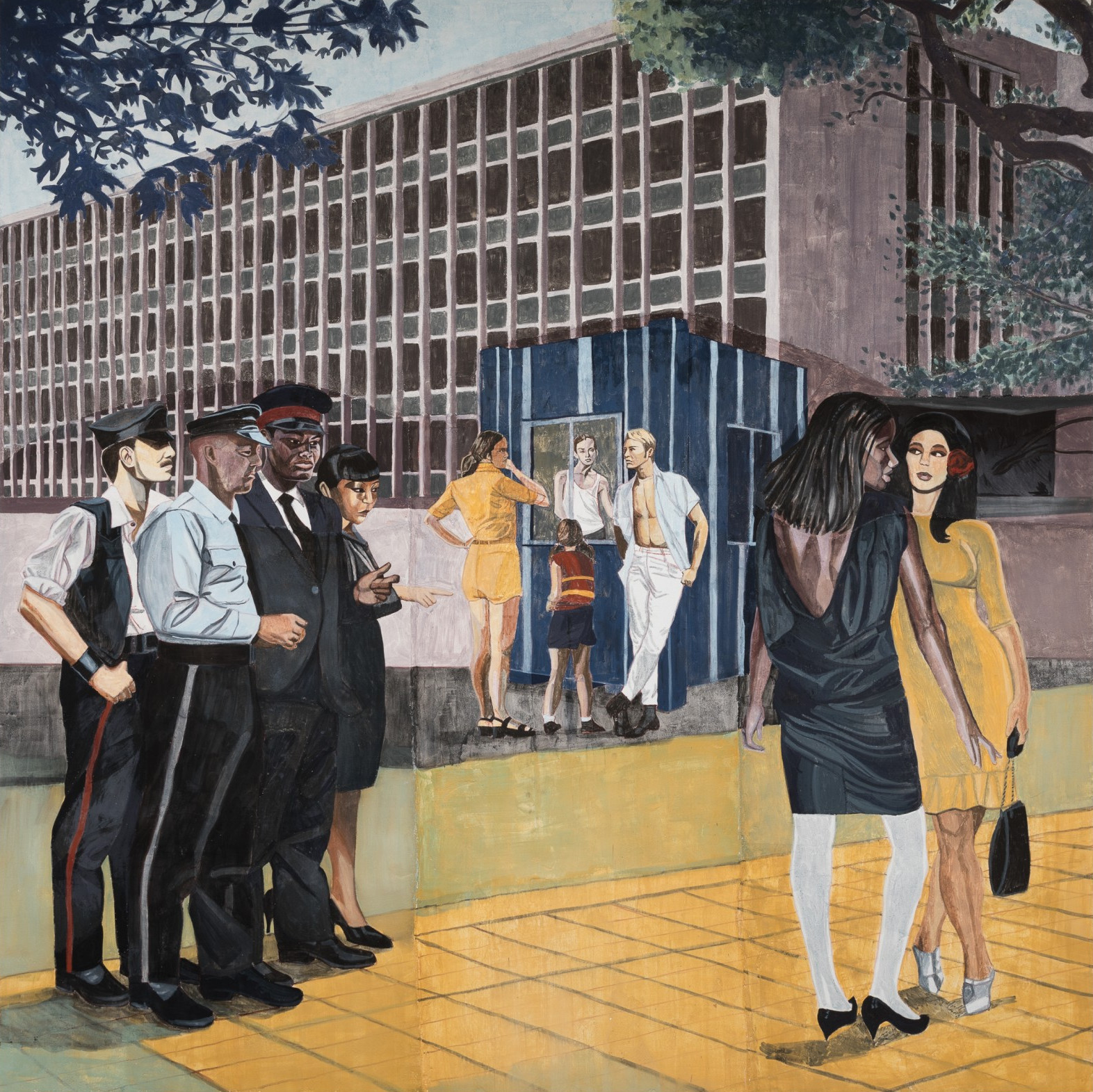

Depictions of postures are more complicated in Quinlan and Hastings’s adaptations of the quattrocento convention. In the Brancacci Chapel frescoes, clothing can function as a visual device carrying ethical implications, either exposing or disguising a figure’s stance. One example is Masaccio’s treatment of Peter and the tax collector in the central scene of Tribute Money. Although the saint’s pose mirrors that of the tax collector, the moral inferiority of the latter is revealed by his unstable stance, clearly visible because he has bare legs, whereas the saint’s rock-solid reputation appears intact as his legs are concealed by the garment he wears. In Quinlan and Hastings’s paintings, modern outfits such as trousers and miniskirts allow legs to become a more visible element in the composition.

In the painting titled Common Subjects, the six figures in the foreground are divided into two groups. The four on the left wear police uniforms, three men in trousers and a woman in a skirt. They are looking at two young women a few steps away, both dressed up and wearing high-heeled shoes. The police all stand firmly, their body weight evenly distributed between their slightly parted feet, a typical Renaissance manifestation of moral authority. The legs of the two women form a stark contrast: one stands with legs crossed, the other adopts a contrapposto, her weight shifted onto her left leg. The finger-pointing of the police at the two women seems to suggest some perceived immoral behaviour. A prison-like kiosk looms in the middle background, ominously suggesting how such encounters can end. However, any hasty conclusion about the gender and racial power dynamics is complicated by the dark skin colour of two of the police officers, and by a group of figures further back at the kiosk. Among them are two half-naked young men, one inside the kiosk, the other leaning cross-legged against it. The figures with upright postures are a woman and a girl, both wearing shorts and both turning away from the viewer.

The style of Quinlan and Hastings’s figures marks a significant divergence from their fifteenth-century inspiration. Masaccio was known for bringing a realistic vision into early Italian Renaissance art through making use of models and incorporating a sculptural approach into his painting. In the paintings of the two contemporary British artists, figures are collaged from street photographs in historical archives taken in Western metropolises such as London, Paris, Berlin, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Their intention, as the artists described in an interview, was to create a ‘horizontal rather than hierarchical relationship to history’. Their colours are conceptual as well as perceptual. The sharp division between the pink pavement and the dark grey street in Disinherited looks more like the edge of Mantegna’s abyss. Yellow is sometimes used to navigate between foreground and background. Tonal gradation appears to have been achieved through a digital process of separating tones into different shapes. These metamorphoses of photographic reproductions play tricks on the viewer. Some figures appear to resemble certain public figures or celebrities at first glance, but just as one feels on the verge of identifying them, the figures become slippery and dissolve one’s sense of déjà vu. The suited man in A History of Morality looks as though he could have walked out of a noir film, but the more one studies him, the more he seems to belong in front of the tulip bushes in the painting.

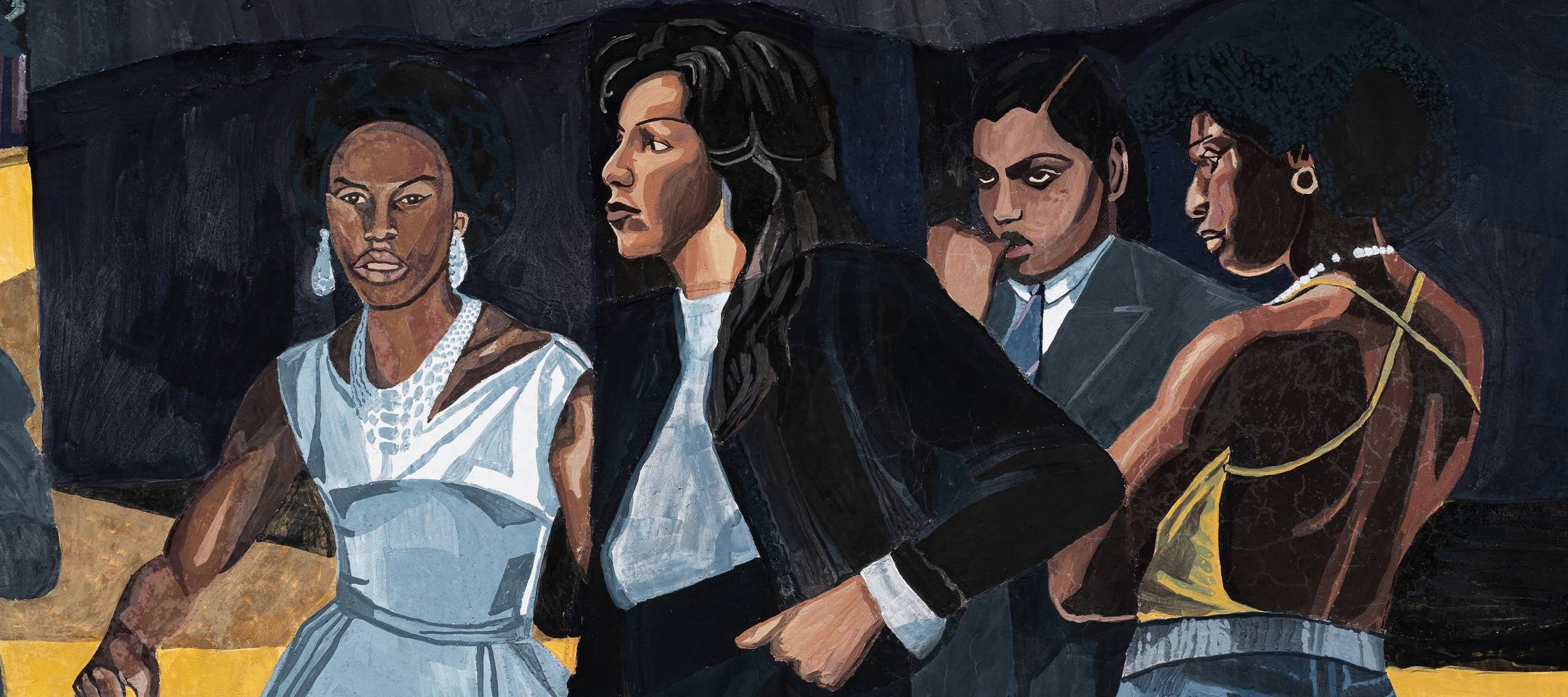

Urban spaces in Quinlan and Hastings’s paintings are rendered in a muted palette and using large shapes, with details kept to a minimum. This creates a world that looks both familiar and strange. Buildings tend to be obliquely located so that vanishing points fall outside of the pictorial space rather than converging on a central figure. Conflicts, which are acted out on street corners, in parks, under the foliage of suburban trees or in public gardens, are open to interpretation. The semi-circle structure, which conveys a sense of camaraderie in the Renaissance frescoes, here signifies exclusion and banishment. In A History of Morality, a woman sitting on the ground apparently weeping is surrounded by a group of people formally dressed as though for church. The garden setting and the woman’s hand covering her face allude to Masaccio’s portrayal of Adam being expelled from Paradise. We don’t know what has happened, but the woman’s humiliation is clear; a woman in a yellow suit bends over and reprimands her, while a policewoman stands by, watching. In another painting titled Expulsion, figures are constructed from archival images of drag queens being arrested in New York night clubs in the 1950s. Superimposed onto a British suburban street, with handcuffs and police officers removed, the painting turns into a choreographed confrontation between two loosely assembled clans, half serious and half playful.

If the police have been deliberately expunged in Expulsion, they are physically present in all the other paintings. In the first three, if one follows the exhibition clockwise, the police occupy a prominent position in the foreground. Their involvement becomes more subdued, however, from one painting to the next. In the first piece, titled Disinherited, a constable raises his right arm with a gesture reminiscent of a Nazi salute to block a woman from walking off the pavement. In the next painting, the arms of the police officers are all bent, their gestures accusatory. The hands of the policewoman in the third painting are behind her back, though visible to the viewer (she is depicted from behind). In both Public Decency and Testimony, the police recede into the background, standing and chatting, as if leaving the disciplinary functions to the women in dress suits in the foreground: to remind the squatting girl of public decency, or to take the testimony of the brawler who stands beside a man collapsing on the lawn. The two passers-by in Public Decency are taken from Masolino’s Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha. While the gazes of Masolino’s onlookers direct the viewer’s attention to the two miracles performed by Peter, the two gazes here – one staring directly out at the viewer and the other a little off to the side – create the uneasy feeling that state surveillance is omnipresent even when it is invisible.

Once the viewer becomes aware of the symmetry in the installation of the six fresco paintings – three on the left with the police in the foreground, three on the right with the police withdrawn – the benches in the middle of the room, where one can sit down and examine the paintings at ease, are transformed into an axis pointing all the way to the drawing on the wall at the far end of the room. Made in 2022 in response to the adoption of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act in the UK, putting more restrictions on protests, the drawing is a pastiche of Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano in the National Gallery, re-imagined with the British police in full riot gear mounted on horses. Medieval armour and spears are substituted for bulletproof vests, flanked by batons and pistols. The eyes looking through flame-proof balaclavas and shielded helmets are equally icy-cold, and the horses are as voluptuous as ever, with their tails carefully groomed. The spectacle of state power is on full display. In the background, haystacks are scattered across fields, where some people are dancing and some are marching, all bearing a resemblance to the figures from the etching series. Between the pastoral scenery in the background and the flamboyant menace in the foreground is a glossy foliage of trees and shrubs populated by pomegranates, roses and tulips.

All this is drawn with graphite, a dry medium that in the hands of Quinlan and Hastings produces a Florentine sharpness and detached clarity. Their communal way of working, unusual among contemporary artists, is another echo of bygone eras of art-making, when, as they observed in an interview, groups of artisans would collaborate in workshops headed by a master (‘We work like artisans, but we have no master’). In the same interview, the artists discuss their approach to drawing: ‘The hardest thing to get “right” is the psychological dimension of drawing; everything else can be achieved in a pragmatic and straightforward way, even talent. The right attitude to drawing is to understand the steps that the image requires you to complete and to follow these steps in an organized and fearless manner. The wrong approach to drawing is to become emotionally involved with the pencil, when this happens you lose perspective and it’s inevitable that you become completely hysterical and unable to perform basic tasks.’

Read on: Marcus Verhagen, ‘Making Time’, NLR 129.