That writing can be a space of freedom is a fraught concept. In its reactionary form, it produces writing that imagines it is free not just to express but identify with every little spurt of fascist emotional aggression that writers can stir from their bowels. There’s no shortage of writing as will-to-power tweeting. Midlist commercial authors pose as victims, looking for something, or someone, to blame other than their own mediocrity for the lack of literary fame – and market share – to which they have an overweening sense of entitlement.

Anglophone modernism often favoured this self-aggrandizing kind of freedom. Fascist, and also usually masculine: Mailer the wife-stabber; Burroughs the wife-shooter. For a writer who appears to the world nominally as a woman, and whose practice of writerly freedom is of a more self-dissolving kind, the problem of creating a public persona as a writer is as acute as that of writing oneself into the freedom of nonexistence.

Kathy Acker was a writer for whom writing enacted a kind of freedom, but of the far more interesting kind. A writing in which freedom did not inflate but rather undermined and dissolved the self. It is writing that is freed in Acker’s work, not the writer. The writing erases and effaces the writer, taking down in the process expected conventions of character, setting, narrative and authorship, tugging away also at the reader’s sense of their own integrity before the text.

To spotlight oneself takes ambition – it takes rather more to immolate one’s self. Thanks to Jason McBride’s definitive new biography, Eat Your Mind: The Radical Life and Work of Kathy Acker, we now have in our hands an account of the genesis of Acker’s ambition and the work it sparked. Acker was born in 1947 to an assimilated New York German-Jewish family who appear and reappear as characters in her writing. Her stepfather comes across as at best useless. Her mother left Acker with an enduring impression of being unwanted. Acker escaped the family in ways both conventional and unconventional. She married Bob Acker, whom she met in college. She outgrew him as a writer, although Acker never became what anyone would imagine as emotionally mature and stable. While there were a handful of sustained, loving relationships in Acker’s life, there were also many brief, intense, fragile encounters (one of them with me).

Acker’s more sustained escape from the bourgeois family was through her uncanny ability to find communities of creative intensity: the New York Filmmaker’s Coop, the St Mark’s poetry scene, mail art, new music, language poetry on the west coast, the downtown art scene back in New York, or new narrative and the cyberpunk scene in the Bay Area in the nineties. Acker was never really of any such scene. She was not a joiner. She assimilated what there was to learn, about formal aesthetic tactics, about methods of being an artist, and moved on.

Her early published pieces were chapbooks circulated through the mail art network, using the address list of one of her mentors – Eleanor Antin. Some were signed with what I think of as a heteronym, a partial authorial persona, The Black Tarantula. The notoriety of these led to her break-out book, Blood and Guts in High School, published by Grove Press in 1984. Grove published most of her subsequent works, including Don Quixote (1986), Empire of the Senseless (1988) – from which McBride takes his title – and Pussy, King of the Pirates (1996).

The work can be read as a systematic destruction of the bourgeois novel, at (almost) all levels. At the level of prose, Acker eschews the ‘fine writing’ of literary fiction. The language is blunt, although Acker gave brilliant incantatory readings. She had learned from the New York poets how to write for the breath. Characters lack a consistent subjective interiority which might masquerade as a self’s private property. Characters become other characters, in other stories, other genres. Just as characters mutate, so too does the authorial voice, at one moment retelling a family story, at another retelling a story from Dickens or Hawthorne.

This freedom with writing rubbed up against the banality of literary ‘culture’, particularly in England, where Acker was embroiled in an absurd ‘plagiarism scandal’. In Acker, language is communism, the product of collective labour. To write is to rewrite. What’s interesting in Acker is always the combinations of material she works on and works over. The sudden jumps from one reworked text to the next, sometimes in the middle of a sentence, crack open the seam between reader and work, pushing against their assumptions of subjective coherence.

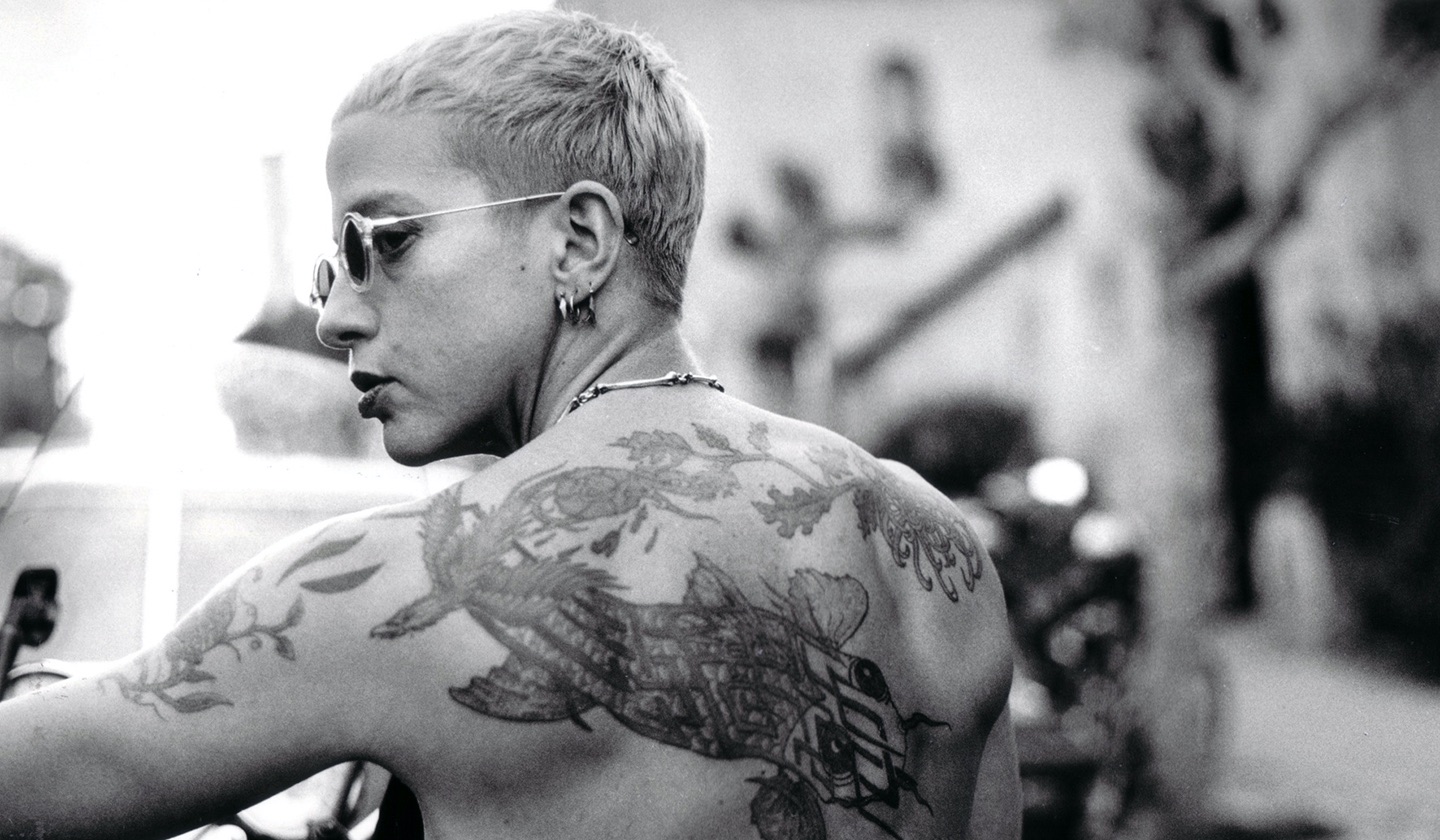

The tension in her work is between this depersonalization of the writing and the persona of the writer. Acker’s writing aimed to abolish private property in language, and yet the books still had to be sold on the literary market under her name and copyright. Given their challenging form, she had to make an image of herself to help sell them, a persona. A persona made necessary by the demands of media and marketing but also for navigating the perils of appearing in the world as a woman making serious claims as an artist. The result was a series of Acker avatars, which Jason McBride elegantly short hands as ‘a deranged kewpie doll, a pirate from the future, an alien courtesan’.

Acker was a mythmaker, fond of inventing fables about herself. While walking through Central Park, she told me her honeymoon was at the Plaza Hotel, adding that Jews had their honeymoons at the Plaza, and WASPs across the street at the Sherry-Netherland. There was no honeymoon. The story isn’t true, except as a way of explaining an internal divide in New York within the class into which she was born.

One of the dangers of biography as a genre is it can render its subject banal – it turns out Great Writers wipe their asses like everyone else. In puncturing the image Acker crafted for spectacular consumption, McBride gives us something more: a narrative account of the struggle of one woman to extend and inflect the trajectory of modernist writing in the late twentieth century. Her aim was to divert its course toward the self-dissolving kind of freedom, which among other things might be a freedom not so much against as beyond the reach of patriarchy.

McBride writes that Acker ‘wanted to live somehow outside of, or in-between, gender binaries’. I would give this more emphasis than McBride. I think this dissolution of the self into the space of writerly freedom was also and crucially a dissolution of gender, or rather of sex, as Acker was far more interested in flesh than social ‘constructs’. Much of her work is also a detailed investigation of the sensations of the body.

Acker never wanted labels, so I’m not going to claim that Acker was trans. As McBride notes, when asked for a sexual identity, Acker claimed it was ‘writer’ – although that takes on added meaning when one understands the kind of shape-shifting writing Acker practised. Rather, I think a dimension of the writing unfolds when one suspends the assumption that the writer is cis. In this case, the assumption that Acker was a cis woman. A dimension of writerly freedom is the freedom not so much from gender as within it.

The will toward freedom within gender is present in Acker’s life as well as in the work. The various, evolving Acker personas were improvised up against the constraints of image-making for the media. Working in the space of appearances is less free than working alone, writing in her endless journals, cross-legged on the floor, masturbating – a practice of Acker’s that I witnessed. Not freedom from gender, which inevitably ends up as some fascist, conformist demand, one particularly punishing toward femininity. Freedom within gender. Rather than being a unitary subject – ‘Kathy Acker’ – there were various Ackers, variously gendered. On the page, in public appearances – and in everyday life.

If one must think through identity labels, this is a way to square Acker’s affinities for queerness with the desire to be fucked, and by men. Sometimes Acker might be a girl, or a woman, being fucked, but sometimes Acker might be a man, or a boy, being fucked, or occasionally doing the fucking. It’s a quality she appreciated in others sometimes too. Among Acker’s lovers, I’m not the only one who was or is or could have been in some sense trans. Acker liked cis men, mostly, and sometimes cis women, but also had an affinity for gender pirates.

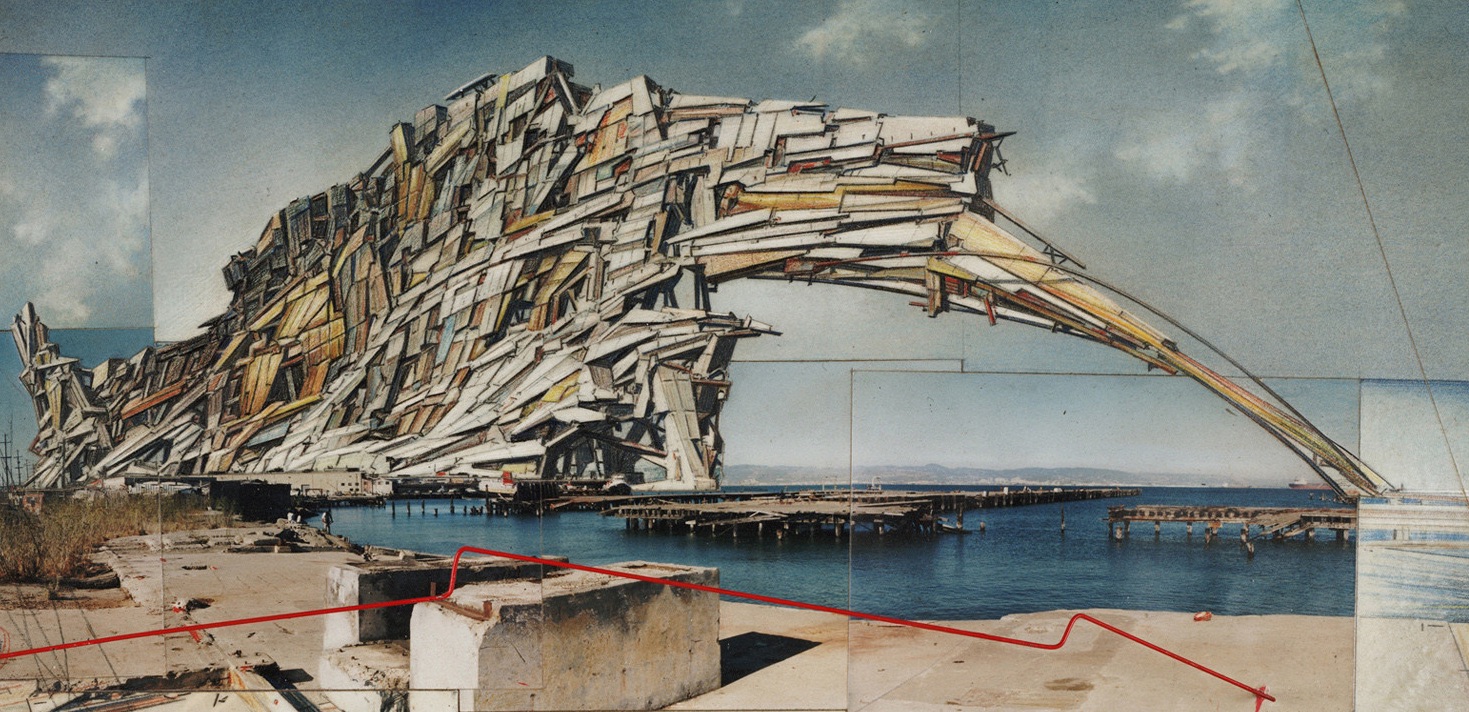

Among Acker’s most consistent personas was the pirate, imaginary avatar of worldly freedom, tacking away from state and capital. But it seemed like you had to be a man to be a pirate. So rather than sail the seas, Acker became a pirate of literature. In the open space of the old ocean of language, Acker could be free, and among other things, free within gender. Acker pirates are mythic rather than historical. They are amoral libertines. The free is not the good in Acker’s philosophy.

Piracy was an allegory for her own methods, and one of her myths. Acker liked the way myths began, as open-ended potential, not how they ended, when the hero slays the monster. The practice of writing is mythic in the sense that once a sentence begins it can go anywhere. In Acker-texts, beginnings never end.

McBride describes Great Expectations, one of Acker’s early books, as a ‘felicitous marriage of mutiny and momentum, rage and humour’. And so it is. Fiction is supposed to be free from mere facticity, but this is so rarely the case. Most fiction is just banal rearrangements of the obvious. Most sentences in fiction end pretty much where one expects. Stories might have ‘twists’, but they still have predictable arcs. Acker’s prose is not like that, and it’s a hard-won quality. McBride documents the various tactics deployed at different stages by different Ackers to undo the relentless obviousness of most writing, including much modernist writing. As he writes, ‘Literature was both her life and her adversary’.

Literature whether high or low was treated not as ‘inspiration’, but as raw material. Acker’s was a materialist practice, a labour of making texts out of texts. Like all interesting writers, Acker was an interesting reader. Through voracious reading, Acker found blocks of text that could be altered, juxtaposed, undone, redone. One might say Acker read ‘sideways’ against the line of the text, unfolding the map of possibilities.

One of the texts from which Acker appropriates is memory. Shards of family life appear in multiple irreconcilable versions. Accidental births, unloving mothers, fathers who aren’t real fathers. For McBride, ‘the negative space of her past, with all its gaps and contradictions, remained a bottomless source of images and provided a kind of prefab pulp fiction’.

From literature, from life, from memory, from dreams, Acker drew the materials for writing as a mythic practice of absolute freedom. McBride: ‘She wanted to replace the old myths, the old superstructures – the double-bind patriarchal ones, the oedipal ones’. The moments of formless possibility in myth are what attract Acker, out of which other narrative practices and cultural forms could be drawn. That we can all make our own myths by cracking open the old ones is her gift to the reader.

It didn’t always work. McBride is one of the few who have noticed the influence of African writers on Acker, particularly Yambo Ouologuem and Ayi Kwei Armah, although I suspect there are others. There’s a book yet to be written on Acker’s complicated relation to race. Attempts at solidarity with anti-imperialist colonial movements tip into a kind of romanticism of the African or ‘Oriental’ other.

In many ways, Acker is still our contemporary. Most of her writing life was spent in New York, the Bay Area and London – three centres of what she sometimes called ‘postcapitalism’. Acker was an acute observer of the nexus of money, sex, art, tech and real estate in these metropolises, where the economy of things came increasingly under the command of an economy of information.

And then there’s Acker’s sexual politics, which owed less to second wave feminism than to sex workers. But for me, Acker is our contemporary mainly in opening up trans-ness as one of the axes of freedom within writing, and beyond. What we might become, on the page, is limitless. What we might become, in life, has to deal with the banalities and constraints of embodiment, on which Acker could write so well. Flesh too can be otherwise, if one reads and writes the languages of the body.

Read on: Julian Stallabrass, ‘In and Out of Love with Damien Hirst’, NLR I/26.