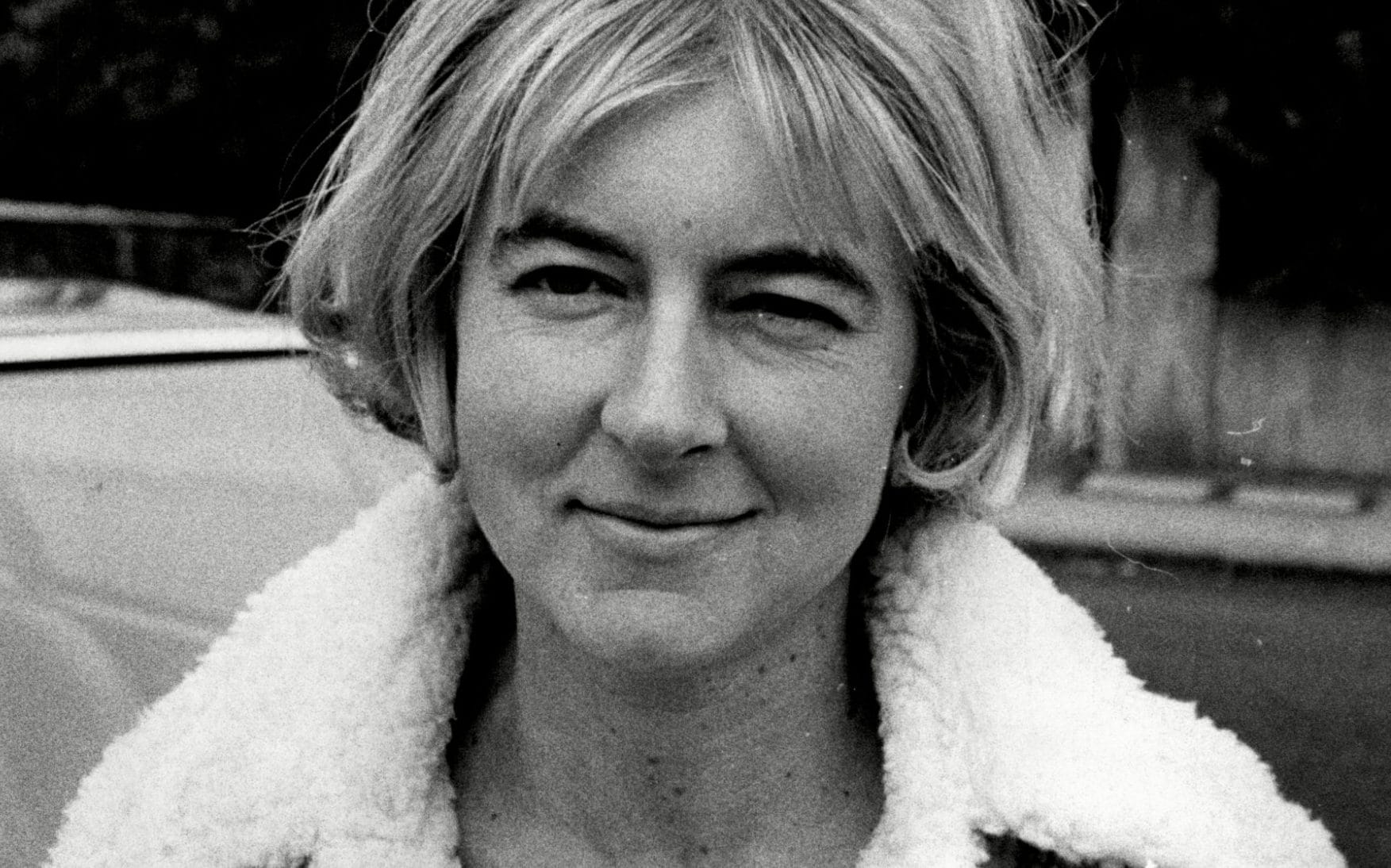

‘Has anyone seen Rosemary Tonks?’ began an unusual announcement in London’s Evening Standard in November 1998. The request was on behalf of the publisher Bloodaxe Books, who were keen to reissue her poetry but explained that ‘we haven’t managed to speak to anyone who’s seen her since the seventies’. At the close of the decade Tonks had seemingly vanished, absconding from Hampstead and her career as a celebrated writer. No further poetry appeared, no new novels were added to the run of six that she’d published between 1963 and 1972, and it was widely believed she’d put a ban on anyone ever republishing them. The collected poems, Bedouin of the London Evening, finally appeared after her death in 2014. An introduction by the publisher Neil Astley revealed that Tonks had in fact been living in Bournemouth. ‘In illness you want to be alone’, she’d once said about her stint in Paris recovering from polio. In 1979, following a series of personal crises – the sudden death of her mother, the collapse of her marriage, burglaries, a lawsuit, an operation to correct detached retinas that left her partially blind for several years – she had retreated to the coast.

Perhaps Tonks had been threatening to do as much in her 1965 poem, ‘Ice Cream Boom Towns’: ‘Hurry: we must go south to escape / The bubonic yellow-drink of our old manuscripts’. An irresolvable restlessness, the sense of being out of joint with yourself and the world, goes back further than her difficulties of the seventies. ‘I was a guest at my own youth’, she writes in ‘Running Away’; ‘My private modern life has gone to waste’ in ‘Bedouin of the London Evening’. The feeling of finding yourself in the wrong life is also present in The Bloater (1968), which has been reissued this month. The most remarkable of Tonks’ novels, it had long been legendarily unavailable. It opens on Min, collapsed with world-weariness – ‘a form of tiredness which is like drunkenness… there are varied layers of brand-new tiredness inside the massive, overall exhaustion, so that you go on falling through one after another’. Later, Min tells Claudi that she’s ‘so miserable and frustrated’ she’d like to ‘lie down in some lousy stinking old Beckett play and just rot there’. Plagued by FOMO after gossiping with Jenny about their respective love lives, she phones up Billy to ask, ‘Am I being left out of things?’ But when Min does find herself properly in the world, she’s shattered by the recognition that her life isn’t her own.

Even prior to disowning her back catalogue, Tonks claimed not to think all that much of her novels. ‘It just proves the English like their porridge’, was her response to an editor’s congratulations on the success of her fifth novel, The Way Out of Berkeley Square (1970). But although the remark’s flamboyant contempt and self-flagellating high-mindedness are classic Tonks, neither The Bloater, nor the rest of her novels, are that. The blurb on the new edition calls it a ‘sparkling’ comedy. ‘Exuberantly jaundiced’ or ‘blithely savage’ might be more accurate – and I’d argue that if the novel merits reappraisal, it’s precisely because of this awkward implacability. The novel appeared disguised as a gently racy social comedy, but Tonks – just like Min, her bristling, incorrigible bullshitter of a protagonist – cannot help but send up the conventions and proprieties of the form into which she’s plotted. It’s one way, short of disappearing, of tolerating not being how or where you ought to be.

The Bloater was originally published in 1968, though it’s not that sixties, but another one, a decade of relentless brown – brown ale, brown walls, brown corridors, brown light, brown days. Min works at the ‘electronic sound workshop’, a fictionalised BBC Radiophonic Workshop, with whom Tonks collaborated on a sound poetry broadcast, Sono-Montage, in 1966. There’s not much youth-quaking modernity here either. The staff are sexually frustrated bureaucrats bunkered ‘like a tinned shepherd’s pie’ down some endless corridor, where ‘the light is so bright you don’t even look ugly. You simply look like yourself’. The one spot of glamour is lovesick Jenny – surely a version of Tonks’ collaborator, Delia Derbyshire – with her bangles and glittered blue-black hair. But Tonks won’t have that either; Jenny’s face is only half made-up ‘until the evenings when she puts on the other half’.

The set-up is a marriage plot turned on its head. Min is married to George, and the novel follows her as she shuttles antically between two alternative suitors. There’s the eponymous Bloater, an exuberantly embodied, man-mountain of an opera singer, as gamey and oily as his cured herring namesake. Min finds him repulsive and cannot get enough of him. Then there’s Billy, who is ‘exact, contemporary, very masculine and controlled’; the way he talks to Min is like ‘a piece of fine dentistry… he stops up all aches and pains’. George meanwhile is hardly there at all. The ‘keeper of unprinted books at the British Museum’, we briefly glimpse the back of his pyjama jacket as he turns over in bed, emanating mute discontent. So vague a figure is George that one night Min switches off the lights in their home and locks up, leaving him eating dinner in the dark. Their house too seems strangely insubstantial, almost as if it doesn’t have any walls, and it’s unclear who lives there. A painting is cantilevered through a first-floor window. A slice of terrine is stored in the glove compartment of a car. Everything is ‘somehow running against the grain’, so that Min continually has to reapproximate the scenes of ordinary life.

But this isn’t really a book that cares about the breaking of marital vows. It is less concerned with bringing lovers together than with Min’s farcical efforts to escape from other people. The Bloater and Billy are two sides of the same coin, representing what Min is trying to avoid: having a body, having to contend with the bodies of others, being seen, being known. In the jacket note for her first poetry collection, Notes on Cafes and Bedrooms (1963), Tonks laid out her poetic ambitions: ‘I want to show human passions at work,’ she writes, ‘and give eternal forces their contemporary dimension in this landscape’. Here, however, she shows Min wriggling this way and that to avoid feeling at any cost. The risk of closeness is ‘all the suffering which is yet to come’.

Desire in the novel is constantly being cast out by disgust. The Bloater is an altogether disgusted book – excessively, theatrically so – and especially with the body: smarting gums, ‘pestilential’ armpits, bed sores, ‘cruel’ fingers, claggy over-powdered noses. Min has ‘the new welfare state disease’, gout, while the Bloater has catarrh. Their entanglement finally ends when she blurts out, ‘I don’t like your smell’. If Min’s not placing the world and the people in it at arm’s length by finding them repulsive, she’s trying to numb herself with what she calls ‘phony pleasures’, or else warding off intimacy with a clenched and calculating defendedness. Conversations are conducted like a game of Battleships. The point is to ‘win’, or, at least, not to surrender, lest your interlocutor colonises your mind or annihilates you. ‘She’s gone too far, and is forcing me to live her life’, Min says of a light chat in the pub with Jenny.

Tonks isn’t much interested in redeeming or absolving her protagonist, though it’s hinted that she shares a background a bit like her own. She does, however, get her happy ending with Billy. Finally, she coincides with herself: ‘I’m not the spectator I’m accustomed to being; I’m not in front of him, nor am I getting left behind.’ But it’s winkingly dashed off, as if to say, come on now, don’t be ridiculous. All kinds of things happen in The Bloater, but the real story is subterranean.

*

Tonks wouldn’t thank you for referring to her as an ‘English novelist’, profiles from the period comment, as if they’re indulging a daft pretension. But she rightfully claimed kinship with a nineteenth-century tradition of French writing, especially Rimbaud and Baudelaire. Her fiction writing, however, with its fascination for the secret chaos that exists between people, is more like her French contemporary, Nathalie Sarraute. Either way, you can understand why she was keen to disaffiliate herself from British literary culture. A 1970 Guardian profile includes the observation that ‘I have never met anyone who was so hurt by critics’. But, reading the reviews, I don’t think it was simply a case of Tonks being sensitive. Rather, perhaps her Francophilia was a response to the prevailing attitudes amongst critics of the time, who were tediously stuck on a nationalist, narrow and incurious idea of ‘the English novel’.

In any case, there’s more to the difficulty of placing Tonks’ writing, and the unhomeliness of The Bloater. In a 1963 interview she comments that ‘I could communicate if only the English weren’t quite so English’. And she wasn’t, exactly, but neither did she belong anywhere else. She was raised and lived mostly in Britain, but her life was profoundly altered by her family’s links to the colonies. Her father died in Nigeria before she was born, in Kent in 1928. She was brought up in boarding schools before joining her mother, who’d remarried, in Lagos, where her stepfather later died. Tonks married at 20 and went with her husband to India and Pakistan for his work, before returning, via a year in Paris, to London in 1953. She’d contracted paratyphoid fever in Calcutta and polio in Karachi, which left her with a withered right hand. Though not a colonial writer per se, she’s not quite an English writer, either. Tonks’ cosmopolitanism is a troubled thing – it’s that of someone who has left parts of herself behind elsewhere and carries elsewhere indelibly with her. In The Bloater, a shift in the light can render London more like Paris or St Petersburg. It’s a less pronounced version of an effect of her poetry, where a familiar London flickers in and out, becoming Egypt or the Baltic Sea. The equator might well run through Chelsea; Covent Garden is full of souks. But she’s not invoking other places as metaphors for some exotic, faraway imaginary. For Tonks, elsewhere is right here, bathed in the same brown light.

*

‘You can cure your reading with your life’, Tonks says, gnomically, during the same 1963 interview. It’s an offhand comment about the anxiety of influence, but the remark has a broader resonance with the way that, for her, living and writing sat uneasily with one another. Early on, her literary work seemed to provide a means to get to the real heart of things. ‘I know that to get through to you, my epoch,’ she writes in ‘Epoch of the Hotel Corridor’, ‘I must take a diamond and scratch / On your junkie’s green glass skin, my message’. But, over time, she came to see the literary world as the thing that had drawn her away from the proper stuff of life. ‘I think it diabolical,’ she comments, ‘this getting of a poet out of his or her back room and the making of them into public figures who have to give opinions every 20 seconds’. Later, this was to harden into violent disavowal.

Throughout the seventies, following the death of her mother, she’d drawn sustenance from various spiritual practices: Sufism, tarot, Taoist meditation, yoga. However, after a period of ill health followed by a series of bizarre supernatural experiences, she came to reject these as diabolical, and instead took up fundamentalist Christianity. She staged a double exorcism in her garden in Bournemouth, burning five suitcases’ worth of ancient Asian, African and Middle Eastern artefacts bequeathed by an aunt, along with the manuscript of a vast unpublished novel about the search for God, as two kinds of false idols. Perhaps, in some way, she was also attempting to vanquish those foreign, restless, unhomed bits of herself. In October 1981, she was baptised in Jerusalem. Born again, she became Rosemary Lightband, discarding the name that feels like an aptronym – at once fearsome and ridiculous, seeming to denote something of its owner’s skinless hauteur – for her married name, though she was already divorced.

I’d like to be able to tell it as a story of refusal, or of mystical transformation, against the typical accounts of people who, like Tonks, just get up and walk away from their lives – those narratives that prescribe the kind of existence it’s acceptable to have, hitting familiar marks: self-destructiveness and self-sabotage, reclusiveness, squandered potential, tragic decline. But it wasn’t. The diaries of her later years record a slow and torturous form of self-immolation. She devoted her attention to the bird song and ticking of clocks that she understood as messages from God. Mostly, she sounds terrified: of the incursions of Satan, the malign influence of other people, even more so of herself and her own mind. She was sometimes to be found commuting up to London to hand out copies of the Bible, the only book she now read, at Speaker’s Corner. In her house just behind the sea front, she worked at painfully winnowing herself away to make a vessel for God’s love.

Clearly, she was intent on making a complete break with her former self. But one can see in Rosemary Lightband a mutation of Tonks’s facilities as a writer into something else. Those same habits of mind – the form-seeking, the heightened awareness, the relentless self-interrogation – metastasized. In a letter to her great-niece from 1987, she writes that her former life was exactly ‘the preparation needed’ for studying the bible, ‘because your mind is alerted to unravelling mysteries hidden in words’. There’s an unassuming passage towards the end of The Bloater in which Min is rueing her domestic failures, but also seems to be reflecting on the source of her difficulties. ‘I know that one of my weaknesses is the fact that I can’t see dust’, she says. ‘I’ve been taught to see the fish lying in a stream, which means that I can penetrate through the glass clothes of a river and see its insides.’ This gift of obscene seeing was Tonks’ too. A writer like her, so vigilant about signs and symbols, so deep within her regime of self-punishment, must have read significance into her misfortune, especially the loss of her sight. Perhaps she decided that if you can’t cure your reading with your life, or your life with your reading, or your life with a different one, you must stop yourself from looking underneath the water.

Read on: Angus Wilson, ‘Condition of the Novel (Britain)’, NLR I/29