Terence Davies, who died late last year, described the final film he made – though he had no way of knowing it would be that at the time – as a love poem. Passing Time was commissioned as part of a project that paired directors with composers, and in the music of Florencia Di Concilio he heard the ‘tentative bittersweet sensation of remembering’. Consisting of a single, still shot captured on an iPhone, Davies shows us a view of the Essex countryside, the spire of a church looming in the distance. Birds rise into the air, lowering to land on the branches of distant trees. Their song rings out and fades into Di Concillio’s score, overlaid with Davies’s rich, low voice:

If you let me know you’re there,

in silence’s embrace; breathe a sigh and tell me so,

for you are gone and not replaced

but echoes of your lovely self will bear us through life’s cruel stream,

and if I am to join you there,

oh what joy your face will bring.

Oh tell me now,

oh tell me all,

for my poor heart with tears is ringed.

We hear the flutter of pages, and then the music swells and the screen fades to black. ‘We recorded the poem twice in my study at home; the first take I dissolved into floods of tears on the final word, and the second take had me shuffling the pages’, Davies explained. ‘I think we chose the best one.’ In these three minutes, we see so much of what distinguished Davies as a director. A love of nature, of music, of poetry, of family – matched by an acute awareness of suffering and loss. The looming presence of religion. The presence of Davies himself, made explicit here by the use of his own poetry and voice. And memory, pressing down like a thumb on a bruise. The poem is dedicated to his sister Maisie – ‘Her loss broke my heart’.

It’s hard to talk about Davies’s films without reference to his biography because the two are so closely entwined. Born into a working-class Liverpool family two months after the end of World War II, Terence was the youngest of ten children. ‘I don’t want to watch violence. I had enough of that in my childhood’, Davies later reflected. ‘My father was a psychopath’. He died when Davies was seven. ‘For about four years, I lived in utter bliss. I was happy all the time. Then I had to go up to secondary school…’ It was around this time that Davies realized he was gay. He struggled enormously. ‘I prayed to God: “Please make me like the others. Why must I be different from them?” Being homosexual destroyed my life. Really destroyed it. In school, I was beaten for it for four years.’ He left at fifteen to become a bookkeeper, prayed until his knees bled, and finally left the church when he was twenty-two. ‘I can’t revisit that’, Davies said of this time in his life. ‘My teenage years and my twenties were some of the most wretched in my life. True despair. Despair is worse than any pain.’

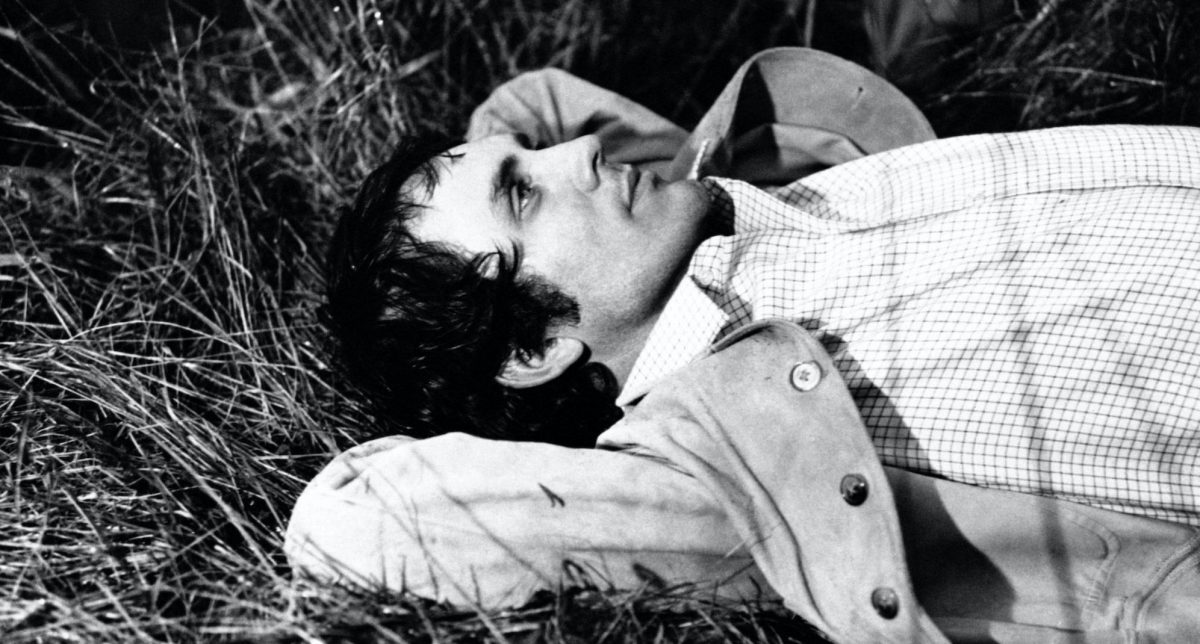

Yet Davies began his cinematic career by revisiting it. His first three films were a trilogy of shorts, Children, Madonna and Child, and Death and Transfiguration (1976-83). They follow Robert Tucker, Davies’s surrogate, through an unhappy childhood into lonely adulthood. While we see the beginnings of Davies’s signature style – long, elegant tracking shots and dissolves, an obsession with the human face, an associative and dreamlike structure that mimics memory, musical anachronism – it is entirely in service of despair. Robert weeps on ferries and in the records room in his office. His sexual fantasies and encounters are haunted, his interest in masochism tormented rather than the playful transgression of a Kenneth Anger or a John Waters. Robert’s only comfort is the love of his mother, whose death devastates him and leaves him with nothing except his own death ahead of him.

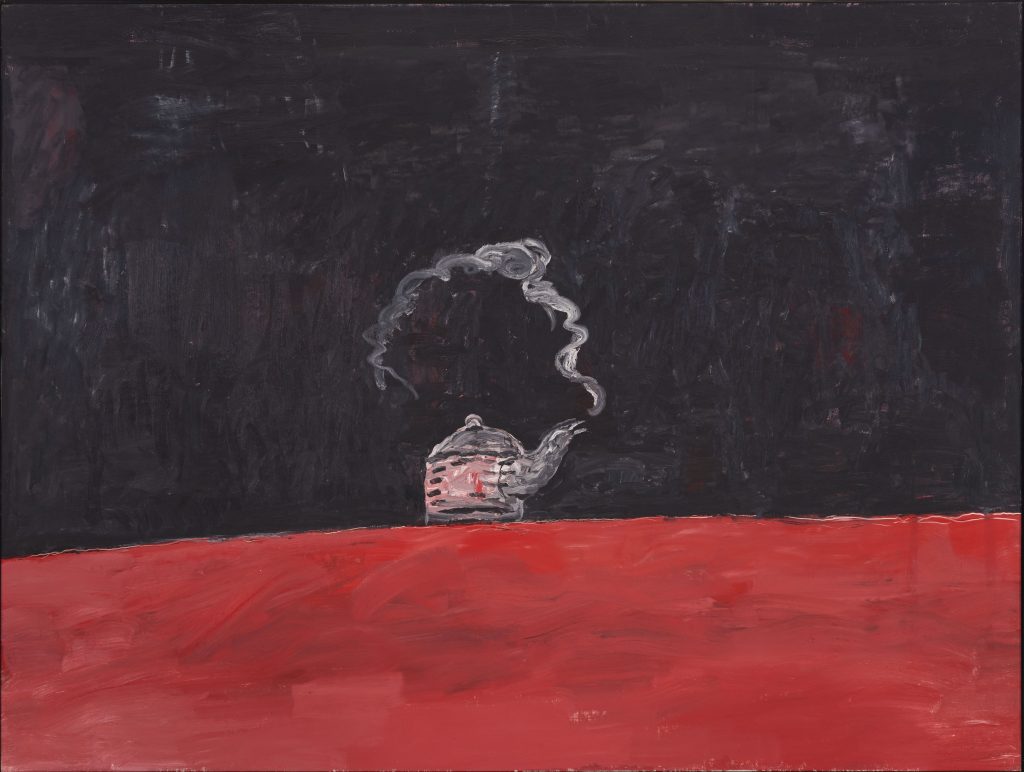

When asked about the choice to shoot the trilogy in black-and-white, Davies mused that ‘the problem with colour is that it does prettify and soften everything – there’s an intrinsic richness you can’t get away from. And I don’t like pretty pictures.’ These are beautiful films, but entirely without solace. ‘I was not only exploring literal truth – my relationship with my mother and father, my religious and sexual guilt’, Davies wrote in the introduction to a collection of his early screenplays. ‘I was also examining my terrors’. It is remarkable that Davies’s next films transcend this mood not by looking to the present or the future, but to the past. As T.S. Eliot writes in Four Quartets, poems which Davies loved so deeply he apparently carried a book of them when he travelled, ‘This is the use of memory: / For liberation – not less of love but expanding/ Of love beyond desire, and so liberation/ From the future as well as the past.’

Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992) draw on the years of ‘utter bliss’ between the death of his father and the awakening of his sexuality. They remain his best-known films. The first was shot in two parts, two years apart, and concentrates on the lives of his older siblings: ‘they were all wonderful storytellers . . . They were so vivid that they became sort of part of my memory, I felt as though I’d almost experienced them’. Davies dramatizes this, reproducing events not as they happened but as he felt them; he shoots from the foot of the stairs, looking out like a child sitting by the door. The Long Day Closes then turns to his own experience. In this sense it covers the same ground as the first of the trilogy, but here the everyday is not haunted by pain but transfigured by the glimmering of memory. Streaks of rain on the windows, projected into oozing drips of light running down the wall. The voice of his mother singing softly in a darkened room; the sun flaring through the clouds for only a moment as they sail by. The whistle of a rod moving through the air as a teacher whips each student in turn. The shadows of two faces glimpsed behind the decorative glass of a door, uniting into one when their lips meet.

At the time of Distant Voices, Still Lives Davies explained that he made films ‘in order to come to terms with my family history’. But by 1992, he had reconsidered. ‘I thought it would be a catharsis, but it wasn’t. All it did was make me realize my sense of loss’. His next film – an adaptation of John Kennedy Toole’s coming-of-age novel The Neon Bible (1995) set in rural Georgia – reflects this. The attempt to transpose his autobiographical concerns into an alien setting led to a strangely shaped film, which was a commercial and critical failure. In spite of moments of brilliance, it is at once too close to reality and too far from it. Davies accepted this, but he also saw it as a ‘transitional work’, insisting that he could not have made his subsequent Edith Wharton adaptation, The House of Mirth (2000), without it.

If The Neon Bible didn’t allow Davies’s style to expand fully, The House of Mirth is perfect for it. You can’t help but feel Davies is having fun, even as Lily Bart descends the social ladder into hell. How could he not, with a heroine firing off lines like ‘If obliquity were a vice, we should all be tainted’? On first viewing, the film plays like a standard melodrama – Davies’s trademark associative style replaced by plot and dialogue. Davies grew up watching ‘women’s pictures’, and the film has much in common with the melodramas of Douglas Sirk or Frank Borzage. As Luc Moullet once wrote about Borzage’s I’ve Always Loved You, ‘the excess of insipidness and sentimentality exceeds all allowable limits and annihilates the power of criticism and reflection, giving way to pure beauty’. The House of Mirth succeeds on similar terms. The more hysterically defeated Lily is, the greater the power of the film – and the greater the power of Davies’s style. When Lily departs on a doomed trip to Europe, Davies slowly tracks through ghostly rooms filled with covered furniture, dissolving and moving through each one in turn until we see a garden doused in summer rain and then, finally, the liquid glitter of sunlight on water.

‘It seemed completely natural to me to make a women’s picture’, Davies said. When asked about his use of music, he revealed why it came so naturally:

I grew up with American musicals. It’s a woman’s genre, as people said then, but for me it was a frame of reference. That’s why there is so much singing in my autobiographical films. For minutes at a time, the camera stays on the singer’s face. Naturally, the songs didn’t do away with the brutality we were subjected to. Yet music was healing. That’s how women are in north England. They’re strong and capable, they have a sense of humour, and they sing. I grew up among these women. Neither the women nor I understood at the time that they expressed their feelings through their songs. Singing changed them, gave them a way to speak about themselves, without becoming too personal.

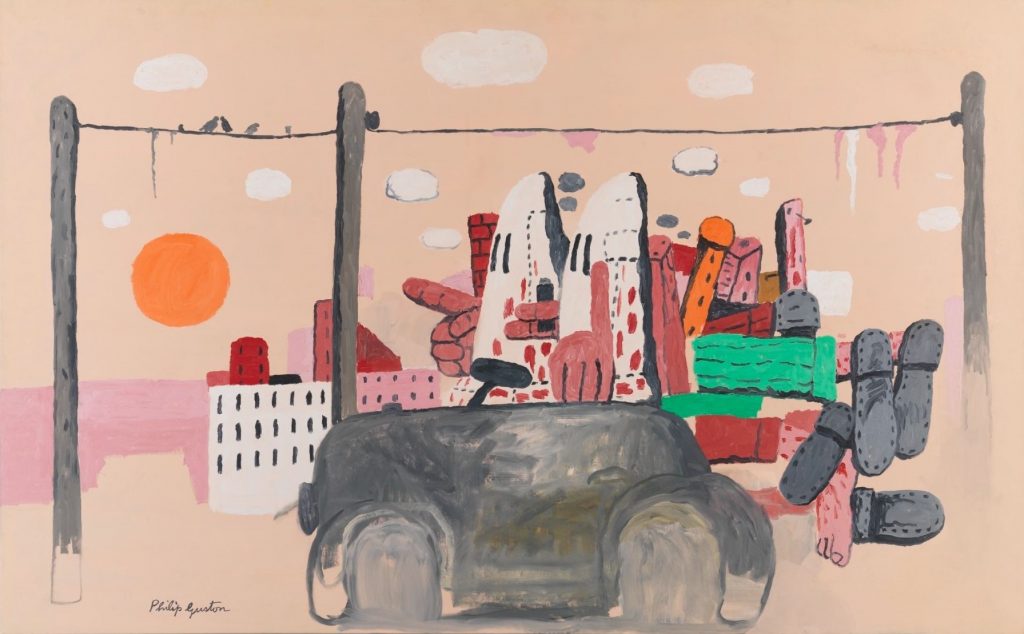

To suffer, to forgive, to learn the trick of transfiguration by turning experience into song. If autobiography had failed Davies, his identification with women’s lives and women’s suffering gave him the freedom of disguise. The House of Mirth was both an artistic breakthrough and a critical success, but Davies was unable to get another film made. He spent years shopping projects around, but they all fell through: ‘I’m sick of not working and having no money. Work is my raison d’etre, and if that’s taken away from me I don’t have a reason to be alive.’ His first films had been made with funding from the British Film Institute Production Board, which was abolished in 2000, and it was only through other sources of cultural funding that Davies found work again. His wonderful city symphony, Of Time and The City (2008), was commissioned as part of Liverpool’s tenure as European Capital of Culture. And his return to fiction, an adaptation of Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea (2011), was commissioned by the Rattigan Trust to mark the playwright’s centenary.

The Deep Blue Sea and Sunset Song (2015) begin where House of Mirth’s sublimation of autobiographical concerns left off. Between them, they have all of Davies’s trademarks: tormented desire, a distaste for religion, groups of people bursting into song, abusive and unstable men, and women who somehow manage. Their heroines bear enormous suffering. Hester’s tormented, adulterous love affair and its painful consequences in The Deep Blue Sea; Chris’s abusive father, returned to her in the form of a doting husband transformed by World War I in Sunset Song. There is a rape scene in Sunset Song so horrible I found on revisiting the film that I remembered it almost exactly: the camera slowly moving closer as Chris weeps and struggles. She screams at her husband to put out the lights, and, mercifully, Davies puts the lights out too – the camera moving down to the darkness under the bed.

But there are also moments of perfect tenderness: Davies’s swooning camera moving through a pub singalong to ‘You Belong To Me’ in The Deep Blue Sea, the camera closing in on Hester and her lover. He sings to her, but she doesn’t know the words – stopping, laughing, watching his lips. And then just the two of them dancing in warm light, the camera pushing in closer still as they rotate slowly, her arms around his neck, clasping hands, kissing. Tenderness and suffering: the world will give you both, but not in equal measure. For Davies, the transformation of life into art was the only way to bear this fact. Perhaps this is why his last two feature films were about poets: Emily Dickinson in A Quiet Passion (2016) and Siegfried Sassoon in Benediction (2021). My favourite – perhaps of all his films, in spite of its occasional awkwardnesses – is A Quiet Passion, where Dickinson’s poetry hangs over the film like mist over water. In a scene where the young Emily sits in a firelit parlour with her family, she looks up at them with a faint smile on her lips. The camera follows her eyes, and we hear:

The heart asks pleasure first,

And then, excuse from pain;

And then, those little anodynes

That deaden suffering;

And then, to go to sleep;

And then, if it should be

The Will of its Inquisitor

The liberty to die.

It’s a moment that’s almost overdetermined – freighted with the relationship between Dickinson’s life and her work, between Davies’s life and his work, between pleasure and pain, life and death. The camera moves slowly around the room, lingering on the face of each family member in turn. It is perfectly silent except for the sound of a clock chiming and the crackle of the fire. And when the camera finally lights on Emily’s face again, something in her has changed. Her eyes glisten and shift side to side as if panicked, her lips turned down faintly. When asked about the scene, Davies said: ‘When we come back to her, I said to her, “But something in you has died,” and I didn’t explain it . . . Because I did that as a child, thinking one day, they will all be dead. And even as a child, I experienced the ecstasy of happiness, but knowing that it wouldn’t last.’

Read on: Ryan Ruby, ‘Privatized Grand Narratives’, NLR 131.