Fame has been kind to Ian McEwan, but not to his writing. Few under the age of fifty remember him as the author of the short story collection First Love, Last Rites (1975), the novella The Cement Garden (1978), or the Cold War spy thriller The Innocent (1990) whose taut, gothic explorations of sexual taboo and violence earned him a reputation as a provocateur and the moniker ‘Ian Macabre’. Starting with the critical success of his Booker Prize-winning Amsterdam (1998) and the commercial success of Atonement (2001), which was adapted into an Oscar- and BAFTA-winning film starring James MacAvoy and Kiera Knightley, McEwan’s plots have slackened into melodrama, and, starting with Saturday (2005), the cool reserve of his narration has succumbed to the temptations of intrusive and unenlightening commentary. With the exception of On Chesil Beach (2007) and Sweet Tooth (2012) – set in the early 60s and the mid-70s respectively – McEwan’s post-Atonement subject matter has been ripped from the headlines. As befits a regular of the international festival circuit with the occasional byline in the Guardian opinion page, his treatment of issues such as the Iraq War, climate change, euthanasia, artificial intelligence and Brexit could be described as narrativized punditry. For this, McEwan has been rewarded with increasing extra-literary prominence. In 2000, he was made a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire by the late Elizabeth Windsor; in 2016, the Daily Telegraph named him ‘the 19th most powerful person in British culture’, an honour at once dubiously conferred and comically specific.

His latest novel, Lessons, finds the author, now an autumnal 74, in the mood to encapsulate his life and career. McEwan lends a number of biographical details to his protagonist, the ‘less-than-brilliant’ cad and dilettante Roland Baines. Among them: the 1948 birth in Aldershot, the working-class Scottish father who works his way up the ranks of British army and class system, the childhood in Tripoli and Singapore, the boarding school education at Woolverstone Hall School (which appears in the novel as Berners Hall, ‘the poor man’s Eton’), the late-in-life reunion with an older brother given up for adoption, the hobbyist passion for scientific inquiry and the news cycle, as well as several of his own published opinions. Everything, it might seem, except literary fame, which McEwan gives instead to Alissa Eberhardt, Roland’s first wife and the mother of his son, Lawrence. Regular readers of McEwan will also find incidents and thematic preoccupations from his earlier novels alluded to or repurposed in omnibus-fashion for this one.

At 481 pages, Lessons is the largest canvas McEwan has worked on; its jacket copy calls it an ‘epic’. Like many contemporary novels so hailed, it is far too short. From its first mentioned incident – which takes place in 1940 – to its last – which takes place in 2021 – McEwan dispatches twice as many years as In Search of Lost Time in a little over one-tenth of the page count. The ‘lost decade’ following Roland’s comprehensive failure at his O-Levels in 1964, during which he pursues odd jobs, tours with a country rock outfit called the Peter Mount Posse, travels as far as Big Sur and the Khyber Pass, and satisfies what he sometimes calls his ‘pathological’ sex addiction, is lost not only to Roland, but to the reader as well. Because the third person narrator does not stray from Roland’s point of view, the lives and motives of the book’s vastly-more intriguing villains – Peter, Alissa, and his Berners Hall piano teacher Miriam Cornell – are left in various stages of underdevelopment.

Everything in Lessons, whose story concludes within a year and a half of its publication date, gives the impression of having been written in extreme haste. Its prose, for example, is pocked with first-order clichés (‘trying to escape his own demons’), second-order clichés (‘a demon he hoped to slay’), dull metaphors (‘Time, which had been an unbounded sphere in which he moved freely in all directions, became overnight a narrow one-way track down which he travelled’), mixed metaphors (‘ten on the pain spectrum’), limp similes (‘Some love affairs comfortably and sweetly rot. Slowly, like fruit in a fridge’), oxymorons (‘a settled, expansive mood’), pleonasms (‘the photograph which would posthumously survive her’), catachresis (‘domestic violence – generally code for men hitting women and children’), jejune diction (‘the creepy shifting shadows’, ‘the magical or silly element’, ‘shivery’, ‘mushy’), trivializing double entendres (‘Lucky too that so far no child was left behind’), pomposities (‘They rose in his thoughts as a black hammerhead cloud of international disorder’), flagrant abuse of self-reflexive questions (‘Would Roland have had her courage?’, ‘What held him back?…Courage. An old-fashioned concept. Did he have it?’, ‘In the face of it would he, Roland, have risen to Sophie and Hans’s courage?’) and barely-concealed cribbings from more talented stylists like Nabokov (‘parenting, its double helix of love and labour’, ‘seven paces up her short garden path, his signature taps at the door – crotchet, triplet, crochet, crochet’). Within the first fifty or so pages, Roland experiences no fewer than three portentous epiphanies, none of which turn out to have any bearing on the subsequent four hundred, as though they were narrative coupons McEwan cut out but forgot to cash in.

McEwan’s novel is not so much an epic as it is three novellas in a trench coat. Novella 1: eleven-year-old Roland is molested by Miriam during a piano lesson and is groomed by her between the ages of fourteen and sixteen, which precipitates the aforementioned ‘lost decade’ and scares him off from intimacy and discipline for the better part of his life. Lessons: our interpretations of events often do more harm than the events themselves; ‘most’ of the ‘problems’ we blame on others are in fact ‘self-inflicted’; forgiveness is essential to freeing oneself from the effects of trauma. Novella 2: thirty-seven-year-old Roland and his seven-month-old son are abandoned by Alissa, who, having witnessed her own mother’s sacrifice of her career as a journalist to marriage and family, decides that being a parent is incompatible with her vocation as a writer, and retreats to a remote village in her native Germany, where she becomes ‘Europe’s greatest novelist’ and a contender for the Nobel Prize. Lessons: just as a ‘cruel act’ which makes a work of art possible ‘made no difference’ to our assessment of them, the ‘quality of the outcome’ did not excuse the cruel act; Roland wouldn’t ‘swap his family for her yard of books’. Novella 3: twenty-something Roland meets Peter and his wife Daphne; the former goes from prima donna lead-guitarist to abusive Thatcherite businessman to philandering Brexiteer and ‘ennobled junior minister in the Johnson government’, whereas the latter becomes his best friend, confidante, co-parent, and – following her Stage 4 cancer diagnosis – second wife. Lessons: reason and fair play are no match for cunning and the will-to-power; making a commitment to someone other than oneself is ‘the best thing’ one ever does.

If this all sounds pat, it has less to do with the necessary evil that is plot summary in book reviewing, than to the didacticism with which McEwan imparts these and other praecepta in the novel itself. Yet perhaps worse than the way the book comes pre-interpreted for the reader is the way it comes pre-criticized. McEwan does not fail to anticipate the objection that what makes Roland’s case notable is that, statistically, male teachers are more likely to sexually abuse their students than female teachers, and that, historically, male artists are more likely to disregard family obligations in the pursuit of their creative ambitions than female artists. Nor, in the novel’s climactic scene, a fight in the Lake District between Roland and Peter over the urn that contains Daphne’s ashes, does McEwan fail to have Roland acknowledge that what the two septuagenarians are doing is ‘absurd’. Indeed it is – all the more so for being a bathetic allegory for Brexit (a Remainer and a Leaver duke it out for the right to bury the ashes of the United Kingdom) as well as a reprise of the fight scene of Amsterdam.

In an op-ed, anticipating objections strengthens one’s case; in fiction, however, it draws unwanted attention to the hand of the author, without whom the particular element that is being apologized for would not exist. Not to put too fine a point on it, but it is hardly exonerating that Roland self-effacingly describes an article he writes as ‘plodding, earnest, lifeless’, and the journals he keeps as ‘hasty’ and ‘without interest’ compared to the writing of his wife and mother-in-law. We do not get to see Alissa’s prose, which is frequently compared to that of Nabokov, who, judging from the synopses Roland provides of her novels, would have dismissed them and – by extension – Lessons as ‘topical trash’.

The trench coat is History. Draped loosely from the backs of these three narratives are hundreds of named political and cultural events, persons, and phenomena, starting with Dunkirk and ending with the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, which range from the genuinely consequential to the merely newsworthy to the unmentionably trivial. The ones that are important to the plot are the White Rose movement (through which Alissa’s parents meet), the Suez Crisis (which precipitates Roland’s return to England from Tripoli and his matriculation at Berners Hall), the Cuban Missile Crisis (which inspires him to pay a call on Miriam so he can lose his virginity before the world ends), divided Cold War Berlin (it is thanks to the Mauerfall that he learns the reason for Alissa’s disappearance and that she will be soon publishing her first novel) and Brexit (which precipitates his final conflict with Peter).

At first it seems as though the effect of ‘public events on private lives’ is going to be the major theme of Lessons. ‘Roland occasionally reflected on the events and accidents, personal and global, miniscule and momentous that had formed and determined his existence’, he writes. ‘His case was not special – all fates are similarly constituted’. McEwan wisely abandons this Forrest Gump-like conceit midway through the book in favour of a much more plausible, if still unsatisfying, depiction of the way citizens of wealthy countries like the UK typically encounter history: as a spectacular entertainment mediated by newspapers, television, and/or the Internet. The historical events appear to serve two narrative functions: as substitutes for the kinds of concrete details other novelists use to convey the quiddity of a character’s experience of the world and as markers for the passage of time. Because of their sheer quantity, however, and because the vast majority of them are simply referred to rather than assimilated into Roland’s consciousness, time feels curiously static in Lessons, which has the unfortunate effect of making the dramatic ‘reckonings’ McEwan stages between Roland and Alissa, Miriam, and Peter seem, well, staged. At a certain point, historical events become little more than narrative boxes for McEwan to check off. He tells us, for example, that Roland ‘made a list of the people he knew who died of AIDS’, but since we don’t see the list, and we hear nothing more of persons who might have been on it, this kind of detail trivializes what it refers to more than if it had simply not been mentioned at all. As with his raiding of female narratives to gin up sympathy for his otherwise undistinguished male protagonist, McEwan’s use of historical events in Lessons is guilty of borrowed gravitas.

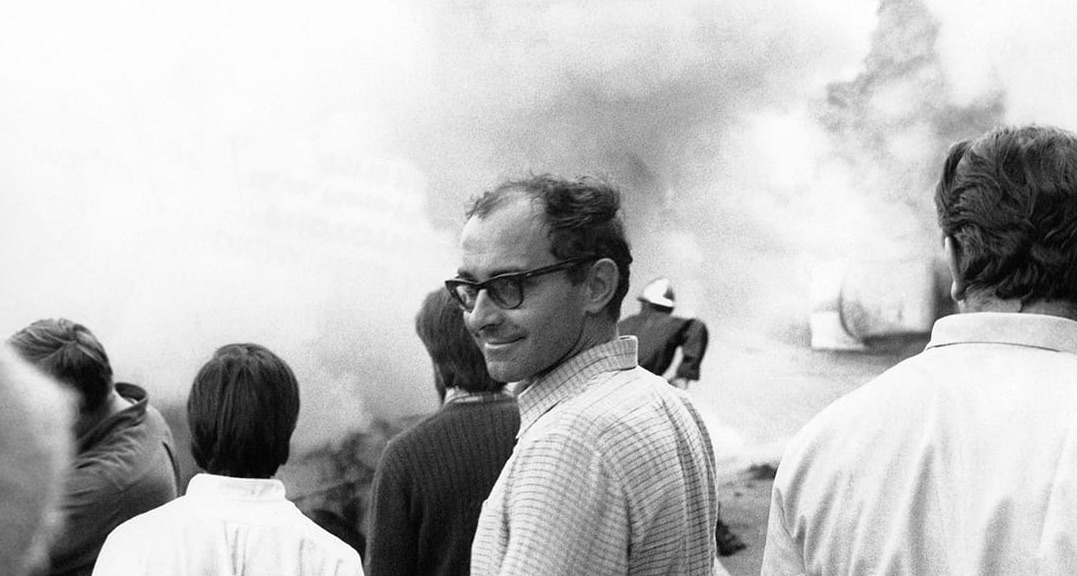

Unfortunately, it is much more difficult to draw lessons from history than it is to manufacture them in fiction. In his final days, Roland rereads the ‘forty journals’ he has been writing ‘since 1986’, the year the novel opens, and which function as its ur-text. ‘Reading back…did not bring him any fresh understanding of his life’, he reflects, and from the single excerpt we have been shown 150 pages previously – which mentions, inter alia, Islamofacism, the NHS, Scottish Independence, Princess Diana, a certain satirical columnist at the Telegraph, and the Booker Prize – it is easy to see why: the journal entries are a mishmash of noted events and reported speech. ‘There were no obvious themes, no undercurrents he had not noticed at the time, nothing learned’, he goes on to lament, as he operatically consigns the journal ‘one volume at a time’ to a fire bowl in his back yard. A self-described ‘centrist’ and ‘liberal’, Roland’s blind spot remains, to the end of his life, his politics. For those who are inclined to examine them a little more attentively than Roland seems capable, at least one ‘obvious theme’ emerges.

Time has done its inevitable work on a number of Roland’s cherished illusions, particularly to his whiggish conviction that economic liberalization produces political liberalization – refuted, in his view, by China – and that history is a slow, but inexorable march towards an ever-more-open society – refuted by democratic backsliding in Putin’s Russia, Trump’s United States, and post-Brexit Britain. Surveying the present, Roland is rightfully anxious about the world he will leave his granddaughter. His ‘bad dream’ for the future is two-fold and incompatible: that the planet will not support life long enough for her to see the end of the 21st century and of ‘freedom of expression, a shrinking privilege, vanishing for a thousand years’, as it had done in Europe during the Middle Ages. A pretty pass, to be sure. Especially for a man who has just torched his complete works.

Assessing his personal responsibility for this turn of events, Roland says: ‘Enough! Those angry or disappointed gods in modern form, Hitler, Nasser, Khrushchev, Kennedy and Gorbachev, may have shaped his life but that gave Roland no insight into international affairs. Who cared what an obscure Mr. Baines of Lloyd Square thought about the future of the open society or the planet’s fate? He was powerless.’ Let us state the obvious: Hitler, Nasser, et al are not gods, but people, as are, a fortiori, Johnson, Cameron, Blair, Major, and, yes, even Thatcher. As he so often admits, Roland is a member of the most affluent and freest generations history has ever known; if he finds himself powerless to secure these privileges for future generations, it is not exclusively due to impersonal forces beyond his control, let alone the whims of a handful of world-historical individuals. Nor is this simply a matter of moral judgment: even if you were inclined to cut Roland some slack on the grounds that no one person ought to shoulder responsibility for the state of the world, a reader, who has at this point been subjected to nearly 500 pages of the views of the ‘obscure Mr. Baines’ has every right to care, not least because McEwan is implicated in them.

Roland spends the seventies as a member of the Labour Party, living in a cheap Brixton flat and leafleting for Wilson and Callaghan. Through his then-girlfriend Mireille, a French journalist with a diplomatic passport, he travels to East Berlin, where he strikes up a friendship with an agronomist named Florian Heise and his family. He returns often to smuggle banned records – Dylan and the Velvet Underground – and books – the classics of liberal anticommunism: Koestler, Nabokov, Milosz, and, of course, Orwell – across Checkpoint Charlie. His friendship with the Heises and his unwillingness to qualify or contextualize his critiques of the political conditions in the GDR puts him increasingly at odds with his fellow Labour Party members back home, who regard actually existing socialism as the ‘lesser of two evils’ compared to US Imperialism. Disgusted by what he perceives as their apologetics and moral equivalence – after all in the West, you are free to listen to ‘Pale Blue Eyes’ and read Animal Farm – he drifts ‘rightward’, in the words of one of them, towards the party’s ‘middle class intellectuals’ who support the ‘democratic opposition’ in Eastern Europe. After Florian is arrested at work, has his house turned over by the Stasi, and is threatened with the breakup of his family – as a result, Roland wrongly imagines, of the illegal reading material – Roland hands in his party card.

When his one-man influence campaign on behalf of the Heises inevitably fails – the family is not broken up but is relocated to the dismal village of Schwedt – Roland pays a tribute to Florian the only way he knows how: with the purchase of tickets to a Dylan concert at Earl’s Court, in ‘a symbolic act of solidarity’. It is June 1981 and for the past three months Roland’s largely African-Caribbean neighbourhood, Brixton, has been undergoing sustained rioting following the Metropolitan police’s Operation Swamp 81, an aggressive, blatantly racist response to protests against high unemployment and dangerous housing conditions in the area. Having spent fifteen pages describing Roland’s time in East Berlin and the plight of the Heises, a tossed-off allusion in a single line of dialogue is all McEwan devotes to the unnamed Brixton Uprising.

Here we have an unwitting parable about the perils of making ‘freedom of expression’ the core of your politics. In the abstract, Roland’s criticisms of the GDR’s censorship policies are not wrong, but as a British citizen, he has no power to change them, and aside from having to listen to disagreement from other British citizens, he will not suffer for his views. Roland’s views are far from fringe – in fact, they are aligned with the ruling party’s foreign policy platform – so his principled stand on the matter is acquired on the cheap. While he engages in consumerist acts of symbolic solidarity with people living in other countries, he does not lift a finger to help his neighbours, who are not only living in worse economic conditions than people in the GDR, but are also suffering, like them, ideologically-motivated repression by the security forces of a state apparatus. It is a state apparatus that Roland is theoretically in a position to do something about, or would be, if he hadn’t just abjured meaningful political activity in a fit of pique.

This is by design. The function of ‘debates’ over ‘free speech’ in neoliberal societies like Britain is not to ensure that citizens retain a potent tool to criticize state policy, it is to defang criticism of its material effects, in part, by deflecting attention, energy, and personnel that might be directed towards raising the tax rate, reducing economic inequality, rolling-back privatization, or preventing a mass extinction event, back on to abstract debates about virtues of free speech, whose opponents are always, conveniently enough, located to the left or beyond the border. In fact, free speech debates are not debates at all – free speech is the condition of the existence of debate in the first place – but are rather a form of political blackmail not unlike the one Squealer levels at the supporters of Snowball in the book Roland smuggles through Checkpoint Charlie for the edification of the thought-policed citizens of the GDR: ‘you wouldn’t want Mr. Jones back would you?’

A self-appointed scourge of secular and religious ‘totalitarianisms’ and the other forms of ‘unreason’ subscribed to by the ‘delirious masses’, Roland fancies himself a man of the enlightenment, but does not seem to remember that on the flipside of the coin that reads Sapere aude is written: Argue as much as you like, and about whatever you like, but obey. He does not see that if he is ‘powerless’ and ‘obscure’ to the extent that no one ‘cares’ about his ‘opinions’, it is because whatever power he might have had he gave away long ago thanks to his rather myopic obsession with ‘the shrinking privilege’ of ‘free expression’. Roland wonders whether he should not perhaps have stayed in the Labour Party after all to ‘argue for its centrist and liberal traditions’, but concludes that he would have been ‘driven miserable and mad after four consecutive defeats’. This is not only a bizarre thing to say of a party which has recently ousted Jeremy Corbyn in favour of Keir Starmer, it is also a rather unfortunate testament to the flimsiness of his convictions. It never crosses Roland’s mind that one of the reasons Labour has suffered four consecutive electoral defeats is because of supporters like him.

Whether free speech really is ‘shrinking’ is – you guessed it – a matter of debate. On the one hand, more speech is being produced by more people than ever before. Yet just as Roland does not regard all repression by state-apparatuses as equally deserving of his attention, he does not regard all speech as equally laudatory. When, despite being a legendary ‘hermit’, Alissa is ‘cancelled’ for making a transphobic joke on an ‘American TV chat show’ – the incident is an allusion to the reaction to a 2016 comment made by McEwan – Roland attributes it to her mix of ‘acerbic rationalism’ and ‘seventies feminism’ rather than to her penchant for verbal cruelty and blithe disregard of others, which he, his son and his mother-in-law have all experienced. Following outcry, an Ivy League university withdraws Alissa’s honorary degree, her speaking tour falls apart, Stonewall and anonymous commentators on the Internet criticize her, and her US and UK sales drop. We are supposed to think that the ‘Young Puritans’ Alissa has offended are overreacting, but it is worth noting these are all instances rather than violations of free expression: private institutions and persons withholding what they had previously chosen to grant – praise, honours, money – according to their best lights at the time. Liberalism giveth and liberalism taketh away.

On the other hand, we need look no farther than the recent assassination attempt on McEwan’s friend Salman Rushdie – the 1989 fatwa against The Satanic Verses is among the events catalogued in Lessons – to concede that freedom of expression is not as secure as we would like it to be. And we may grant that, as a novelist, McEwan has a legitimate interest in its preservation. But it is precisely qua-novelist that he has a special responsibility to freedom of expression that goes above and beyond that of the pundits who argue in its defence in op-eds or even that of advocacy groups like PEN that raise money and awareness on behalf of writers around the globe who have seen their work banned or who have been imprisoned, attacked, harassed or murdered for publishing it. It is this: to create a work of literature whose aesthetic power justifies the privilege in the first place. Without such power, all we have is yet another commodity – far too disposable a peg on which to hang the values of an entire civilisation. Just as people living behind the Iron Curtain had no shortage of reading material as mediocre as Lessons, the market is currently condemning far better books than it to smaller print runs than a samizdat. A bestselling, Booker Prize-winning Commander of the British Empire, McEwan is not obscure, nor is he powerless, according to the Daily Telegraph. Lessons was written in perfect freedom. What did he need it for?

Read on: Francis Mulhern, ‘Forever Orwell’, NLR 87.