The crisis of English government that has gathered pace since 2016, accelerating further in the context of the Covid pandemic, has frequently revolved around the predilections and vanities of three men: Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings. The three were bound together by the Vote Leave referendum campaign, but already belonged to the same intellectual and journalistic milieu, whose political implications appear increasingly stark. It is brash, disruptive, libertarian and disdainful of liberal-conservative establishment norms, including those of the legislature, judiciary and civil service. Media-savvy, it seizes on hot-button ‘cultural’ issues to distract from less spectacular (but usually more consequential) economic decisions being taken elsewhere. If this ideology has a basecamp from which to mount its assaults on the state, it is not – as was the case for Thatcherism – a post-war think tank, but a Georgian magazine: the Spectator.

In April of this year, commenting on how the government appeared to be stoking a new ‘culture war’ amidst the Covid emergency, the political editor of the Financial Times, Robert Shrimsley referred to the ‘Spectocracy’ that was driving it. Johnson, who was editor of the Spectator from 1999-2005 is clearly this faction’s totemic leader, but Cummings (who departed Downing in Street in November) held a position as online editor, which he resigned in 2006 shortly after insistently re-publishing a Danish cartoon of the Prophet Mohammad. Cummings was hired as Gove’s advisor the following year, but still occasionally uses the Spectator blog to issue his over-wrought meditations on the state of politics, while his wife, Mary Wakefield, has held a succession of senior editorial roles at the paper since Johnson’s tenure.

Shrimsley was also referring to the role of libertarian provocateur Toby Young, an associate editor, who has refashioned himself as a free-speech campaigner and ‘Covid sceptic’ who seeks to challenge expert opinion on policies such as lockdown. He might equally have mentioned the magazine’s political editor, James Forsyth, whose wife, Allegra Stratton, has – with great media fanfare – recently been appointed Downing Street press secretary. At their wedding, Forsyth’s best man was none other than Rishi Sunak, now Chancellor of the Exchequer. The cultural front of this new conservatism has been pushed in alliance with the Daily Telegraph, with whom the Spectator has shared the same owners – Conrad Black and then the Barclay brothers – and many of the same columnists and editors since the 1980s. Johnson’s December 2019 electoral triumph, built solely on the promise to complete the Brexit process, represented a startling coup for a clique that had spent much of the previous two decades trolling and trivialising politics.

In 10,000 Not Out, David Butterfield, a young(ish) Cambridge classicist, author of books on Lucretius, Varro and A. E. Housman and regular Spectator contributor, offers a lovingly told history of the magazine, its key characters, controversies and fluctuating readership. As Butterfield underlines, the Brexit era is not the first time that careers have zigzagged between Westminster and the Spectator. Previous editors include a sitting Conservative MP (Iain Macleod, 1963-65) a future Conservative Chancellor (Nigel Lawson, 1965-70), and Margaret Thatcher’s official biographer, newly ennobled by Johnson (Charles Moore, 1984-1990), while among its mainstays have been such figures as Thatcher’s policy advisor, Ferdinand Mount. Johnson combined the editorship with a parliamentary seat, plus stints as deputy chairman of the Conservatives and as Shadow Arts Minister. His successor, Matthew D’Ancona, was closely involved with David Cameron’s efforts to shift his party to the centre, and remains chair of the Cameronite think tank, Bright Blue.

This level of intimacy between a political party and a publication would be significant enough. What’s stranger is that the Spectator has frequently been at pains to stress its ambivalence towards the Conservative Party. Every incoming editor appears to have felt compelled to make the same self-regarding declaration of independence and lofty intellectual aspiration, no matter how personally entangled with the party they may have been. Some (like Cummings) appear to have held the Tories in some contempt, while fraternising and gossiping with them for a living. Perhaps they doth protest too much, and this rhetoric of independent mindedness is simply how the establishment likes to present itself. On the other hand, there is something distinctive about this restless branch of conservatism, which is constantly on the verge of attacking the very institutions it claims to cherish. Since this is the culture that has shaped Britain’s latest political elite, Butterfield’s impressively researched if hagiographic book might be read as a kind of history of our unhappy present.

The Spectator was founded in 1828 by Robert Rintoul, a Scottish journalist with Whig sympathies and a progressive Benthamite perspective on social reform. Rintoul deliberately revived the title of the famous but short-lived coffeehouse periodical, established by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in 1711, and Rintoul’s descendants have occasionally muddied the waters surrounding its true origins (the Spectator blog is named ‘Coffee House’). Like the Economist, which became something of a sister when it was founded fifteen years later, its main political concern was to defend and extend free trade. Beyond this core liberal principle, Rintoul hoped that his paper would avoid political partisanship, and instead focus on offering a form of intellectualism and heterodoxy that its readers would revere and learn from.

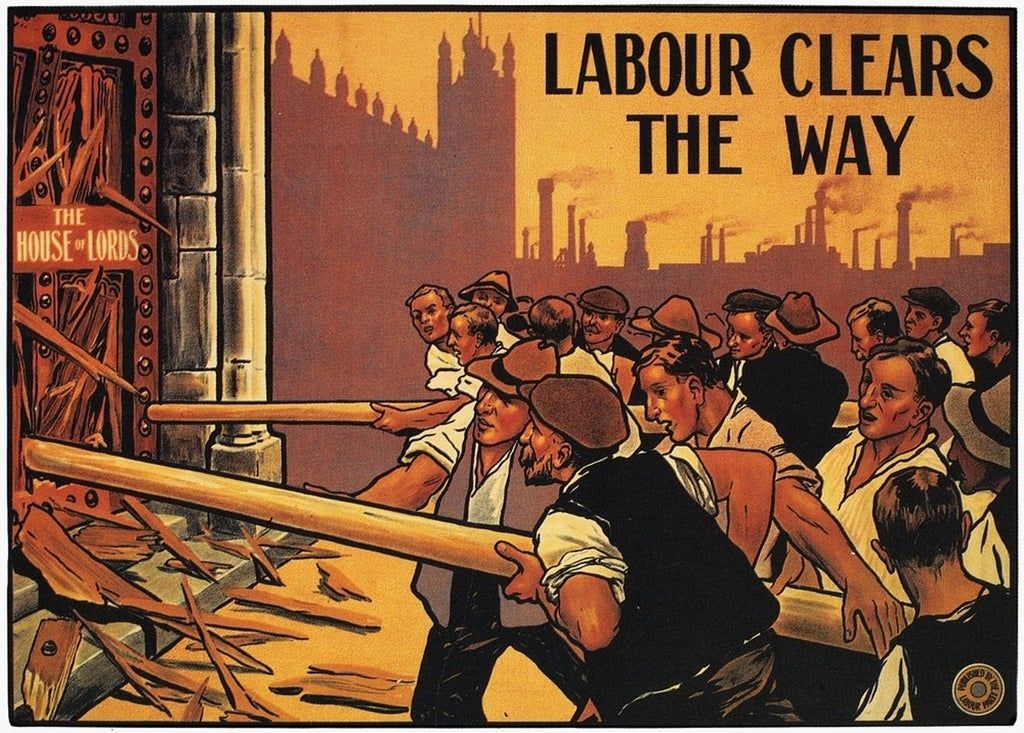

Coinciding with the heyday of Victorian laissez-faire, the early decades of the Spectator placed it firmly on the side of political modernity. Despite its stated desire to remain a neutral spectator of politics, it was forced off the fence where key liberal objectives were at stake, offering whole-hearted support for the 1832 Reform Act, then (less popularly) opposing slavery and backing the North in the American Civil War. John Stuart Mill was a frequent and enthusiastic contributor, while Butterfield reports that ‘the paper’s admiration for Gladstone had risen almost to the point of idolatry by the mid-1880s’.

The Spectator first turned on the Liberal Party over the issue of Irish home rule, which cost it a considerable number of readers, whose loyalties were to party before newspaper. By the close of the nineteenth century, the paper could boast a famous litany of literary contributors – Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle – but its progressive credentials (both culturally and politically) were growing shaky. It wasn’t until the 1930s that the Spectator was firmly supportive of the Tories (a stance embedded in a vehement anti-socialism), by which point it had also undergone a brief flirtation with Mussolini.

Yet the existential dilemma of liberalism versus Toryism has never entirely deserted the paper. The cultural world of its writers is unmistakeably that of a fading public-school and Oxbridge elite, whose access to political power has been routed via the Tory Party for the past century. But in addition to its early attachment to laissez-faire, its social values (not to mention the lifestyle choices of its leading lights) have been liberal and individualistic, to an often provocative degree.

The dilemma is constitutive of a certain strand of conservative liberalism, which is (somewhat paradoxically) nostalgic for the Victorian model of progress. Various means of squaring this circle have been sought, most powerfully the modernising neoliberalism of Hayek and Thatcher, which sought to reinvent and reimpose laissez-faire. Never sufficiently committed to economics to add much to that agenda, the Spectator has clung to a different strand of ‘classical liberalism’, the rhetorical acrobatics and innuendos of the gentleman’s club and the Oxford Union, which ultimately resolves in the self-serving free-speech activism that has become the contemporary Spectator’s greatest cause célèbre.

The perpetual editorial declarations of political independence and liberal intellectualism continued after the War. Graham Greene, Kingsley Amis, Phillip Larkin, Iris Murdoch and Ted Hughes were all occasional contributors, though Butterfield notes that the paper never quite got modernism or anything that smelled of the avant-garde. Social liberalism continued to inform the policies it advocated, including opposition to the death penalty and support for legalisation of homosexuality. In 1958, Michael Foot wrote to say that ‘no journal in Britain has established a higher reputation than the Spectator for the persistent advocacy of a humane administration of the law or the reform of inhumane laws’. Nigel Lawson’s paper attacked Enoch Powell’s infamous 1968 ‘rivers of blood’ speech as ‘a nonsense and a dangerous nonsense’.

The distinctive Spectator tone of reactionary satire, later advanced in cruder form by the likes of James Delingpole and Rod Liddle, was apparent in 1968 via the pen of ‘Mercurius’, a pseudonymous academic who railed against student protesters, social science and expansion of higher education. It seems fairly clear, though never confirmed, that the author was Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. Beyond such fripperies, what’s surprising is how little of substance the Spectator contributed to the resurgence of the right over the subsequent decade, especially given the critical importance of other print media (Samuel Brittan and others at the Financial Times in particular) to the spread of Thatcherite ideas. Lawson briefly positioned the paper as pro-European, though this was swiftly reversed by his successor George Gale, under whom the Spectator’s financial position and profile slid.

As for the country, so for the Spectator, 1979 proved a turning point. Under the accomplished editorship of Alexander Chancellor (who professed never to have voted Tory), Moore (who described himself as an ‘independent Tory’) and then Nigel Lawson’s son Dominic, the magazine became more spirited and increasingly hedonistic. Sales rose, as did the quantity of provocative and racy content. Thatcherism provided the backdrop, but the sense one gets from the Spectator of the 1980s is of the old patriarchal establishment becoming drunk on the freedoms of the revived laissez-faire.

Yet to grasp the cultural roots of the present political crisis, and to some extent of Brexit, it’s the Blair era that deserves closest attention. Beyond its enthusiastic support for the Iraq War, the paper found it difficult to gain a political toehold with respect to Blairism. After all, London in the late 1990s was everything that rich and well-connected social liberals could ever have hoped for. Unable therefore to offer serious or substantial criticism of the New Labour government, the Spectator under Johnson began to take libertarian swipes at what he called the ‘ghastly treacly consensus of New Britain’. Young joined in 1999, and Liddle jumped ship from the BBC three years later.

Offence-giving became a mark of intellectual freedom and was steadily ratcheted up under Johnson. William Cash, son of the Eurosceptic MP of the same name, asserted that Hollywood was the fiefdom of a Jewish cabal. Taki, a far-right lifestyle columnist, wrote of New York Puerto Ricans that they were a ‘bunch of semi-savages’ and that ‘Britain is being mugged by black hoodlums’, before later praising the Wehrmacht. In 2004, a Spectator leader repeated the lie that ‘drunken fans’ were culpable for the Hillsborough football-stadium tragedy, whose memorable death toll (96) the paper could only put at ‘more than 50’.

Throughout this period, anti-European barbs were being tossed on a regular basis, in tandem with the rest of the conservative press. Given how few steady ideological positions the paper seems to hold, the persistence of anti-Europeanism – following Nigel Lawson’s brief effort in the 1960s to embrace European integration – has become one of its most significant political identifiers, at least since the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. Butterfield treats as obvious that a publication committed to ‘free trade’ would adopt this stance (which unsurprisingly resulted in support for ‘Leave’ in the 2016 referendum) but this is to underplay the nationalist undercurrents of both Brexit and the contemporary Spectator.

Much of the time, this Euroscepticism is too flippant and jingoistic to count as a credible policy vision. As with kitsch Brexiteer appeals to ‘Global Britain’, it is rooted in nostalgia for a 19th-century modernity when you could ‘say anything you like’, cultural hierarchies were explicit and government supposedly did as little as possible. Since Thatcher left office in 1990, what Brexitism has offered subsequent generations of conservatives is a way of going ‘meta’ on the establishment that spawned them, distancing themselves from orthodoxy and authority, in the name of some higher freedom. The squaring of the liberal-Tory circle ends up in adolescent efforts to cause offence for its own sake, but the political side-effects have turned out to be far more serious.

The identity of William Cash – son, not father – has been corrected. Thanks to the Sidecar reader who pointed this out.