Socialism is a story on the streets of the twenty-first century city. A lot depends on the teller. There was a mayor’s race here on November 2. One of the candidates called herself ‘a proud socialist’, a ‘democratic socialist’. Her opponents called her a ‘radical leftist’ and ‘dangerous’. An editorial cartoon in the daily newspaper in June, shortly after she upset the four-term incumbent mayor of this Democratic city in the Democratic Party primary, depicted her benevolently extending City Hall to a throng of outstretched arms. By October, the incumbent having decided to run a write-in campaign premised on the unique peril posed by this upstart, the newspaper decided that it too found her a ‘threat’. She is four feet eleven inches tall. In her pitch to voters, socialism amounted to advocating an economy and society that worked for everyone; she seldom used the term. Leftish commentators nationally rhapsodized about socialism taking the reins of power in Buffalo, and got almost everything wrong. The Erie County Democratic Party chair said talk of radicalism was ridiculous: ‘she sounds like FDR’. ‘Write-In’ came out ahead on November 2, an indistinguishable heap that didn’t officially return the incumbent mayor to City Hall until late November, once his votes were separated out from those for Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, the Buffalo Bills’ quarterback and a few candidates who also ran as write-ins, though mostly invisibly. Election night returns were robust enough, though, to relieve some contributors to the newspaper’s letters section that Buffalo had been spared from becoming North Korea on Lake Erie.

Words are pesky when they have no agreed-upon meaning.

Young woman waiting for the bus: ‘Socialism? I heard that word back in school, in history class, but … I can’t remember.’

Young man waiting for the bus: ‘I know exactly what it means. To be sociable, you know, just socializing, talking with people, over the internet, just everywhere, everywhere.’

Old man getting on the bus: ‘I wish you’d asked me first. [gruffly] I’ll tell you: Joe Biden.’

***

Socialism is a history in fragments in a fragmented city. Walking distance from my natal home there is an empty lot. There are many, actually, but 1644 Genesee Street, next to Ike and BG’s BBQ and across from Island Food Mart, a bodega defenced by door and window grates, once denoted the East Side Labor Lyceum. The building is said to have survived until 1991, though I don’t remember it. A stone’s throw away, a small but handsome brick structure where I checked out books as a girl has not been a library for decades, but the central library downtown yielded a few details. A Sanborn map from 1939 is allusive: a deep, narrow building; a ‘Hall’ on the second floor. A squib from the Buffalo Courier in 1915 announces that the lyceum’s cornerstone would be laid on April 11 of that year, a Sunday. ‘Preceding the ceremony there will be a parade of children and men and women interested in the project.’ A ‘Socialist organizer of Buffalo’ got top billing among the speakers, who also included a Presbyterian clergyman and Mrs. Frank J. Shuler, representative of the Woman Suffrage party. A reminiscence in the Courier Express from 1950 mentions ‘the old time Socialist soapboxes … They used to hold forth regularly, orating from improvised stands at Main and Mohawk, Main and Genesee and other points throughout the city’. The card catalogue in the local history reference room discloses little more, but the librarian found regular announcements of meetings, socialist lectures and card parties at the East Side Labor Lyceum while scrolling through a news database. A dissertation on the role of interior spaces in the formation of working-class consciousness reports that Buffalo had a kind of floating lyceum, a regular lecture series or salon under various roofs, as early as 1904. A sentence in a Daily Worker story from 1924 mentions a Labor Lyceum in another part of the city’s East Side, this one at 376 William Street, near Jefferson, the commercial drag of black Buffalo by the time of my youth. That address today is also an empty lot.

Nothing marks the radical past. Labor Lyceums, typically the undertakings of socialist German immigrants, replaced saloons as primary spaces for union meetings, educational events and working-class entertainments in many industrial cities around the US in the early twentieth century, but I hadn’t thought about their existence in Buffalo until I stepped into a saloon, sort of – the Eugene V. Debs Hall, a former Polish bar, beautifully restored last year and, once the state approves its liquor license, one of two taverns that remain in an East Side neighbourhood that used to be thick with them. People, some my relatives, once crowded the streets of this area; wildlife is common now. A deer loped across the street toward my car the night I visited the Debs Hall to talk with its founder and principal manager, Chris Hawley. The flock of wild turkeys that also frequent the neighbourhood must have been sleeping or shy.

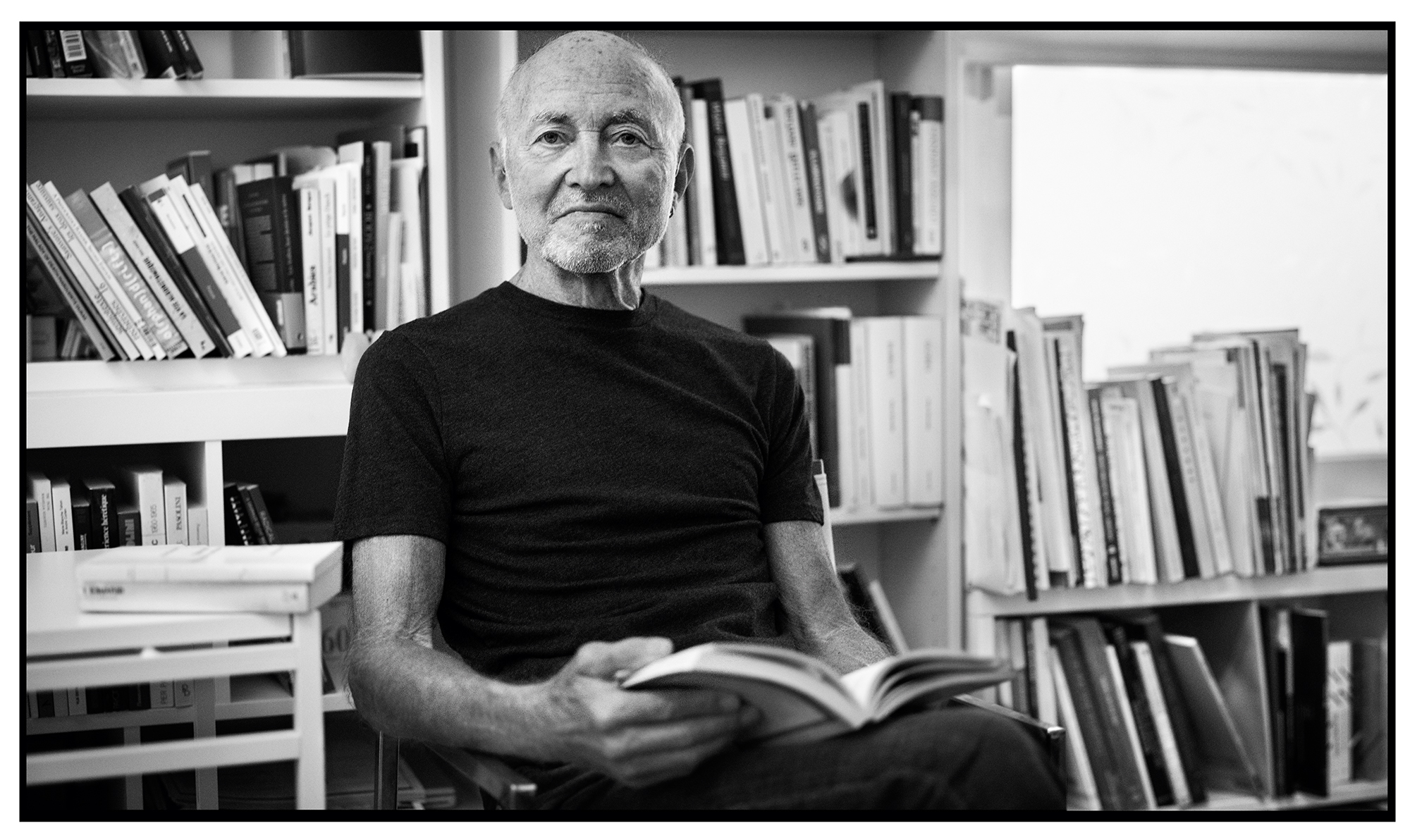

Hawley is a senior planner for the City of Buffalo. He lives in the back of the tavern with a cat named Sputnik, whom he rescued from certain death on the street, and bikes to City Hall, fifteen minutes away. As an avocation he researches the histories that have been erased in what, in so many other ways, is a landscape of memory. Ten years ago, thousands of preservationists from across the country gathered for a conference in Buffalo, marvelling at the works of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, at the daylight factories and grain elevators that had inspired Le Corbusier but, even in those cases, abstracting the architecture from the lives that had built and animated it. Hawley wasn’t in his present job at the time. He was born here forty years ago, into a family that, on one side, traces its early twentieth century heritage to skilled work and upward mobility from the beginnings of the once-gargantuan Bethlehem Steel works; and that, on the other side, preserved the silences of a working class left to fend for itself – the railroad worker killed on the job, his widow with eleven children, the rough boarders to whom she’d rent out the children’s beds, the violence of everyday life. Hawley’s parents were part of the migration out of Western New York to the Sun Belt. He began unearthing labour histories when he moved to Buffalo after university, piecing together the shards of experience that help decipher a project like the Eugene V. Debs Hall today.

Workers associations were numerous when the building was erected in the Broadway/Fillmore district not far from the city’s vast railyard and stockyards in 1899. It was always a bar, and because, according to a 1901 report by Temperance advocates, all but six of Buffalo’s sixty-nine labour organizations met in saloons or halls connected to saloons, it’s possible that the proprietors of this place augmented their income by renting space to unions. In any event – even allowing for the contradictions of the saloon as a male space, a white ethnic (here specifically Polish) space, a drinking and so potentially disabling space – the bar would have been a communal hearth, locus for workers to forge bonds against the fragmenting processes of industrial capitalism. Especially once it was spruced up in 1914, it likely played the social role of so many taverns, as a site for small wedding parties or funeral repasts, christening fetes and other celebrations. By then, Hawley says, ‘Buffalo was a hotbed of the Socialist Party. Debs had come here in 1898 to form the first local. There were twelve locals in the city, several in the outlying towns; mainly they met in taverns or other halls.’ The East Side Labor Lyceum was a step up, built by the Socialist Party specifically for socialists. He has a picture of its drum corps, a cartoon from 1917 of ‘The Regular Meeting of the Branch’, a reproduction of its mission statement: ‘Dedicated to intellectual advancement of working people and to prepare them for the abolishment of the system of exploitation and profit.’

Graduate student, political philosophy, 30-ish [coolly]: ‘Socialism is the first stage of state control of all means of production and distribution. It’s command central … Socialists are communists.’

Firefighter, middle-aged: ‘Socialism is the practice – the practice – of equality.’

***

Whatever else it was, the recent mayor’s race was a public confrontation with inequality. The dominant boosterist story of contemporary Buffalo is abbreviated as ‘Renaissance’. In the miserablist press the story is typically abbreviated ‘disaster’. Neither suits the whole.

Deer are not wandering everywhere in the city, and even where they tread, the grassy plots represent progress from the thousands of firetraps, shooting galleries and condemned hulks that a working class stripped of its livelihood – by the collapse of steel and then domino-like deindustrialization – had once called home. Buffalo’s population was 532,759 in 1960; it is now 278,349, a bit higher than in 1890. The latest census reflects an uptick, driven most dramatically by new migrants. On the East Side, which for decades has been predominantly black with a Polish remnant, the newcomers include at least 10,000 (possibly 20,000) Bangladeshis, many who fled the high costs of New York City and then encouraged relatives from the old country to join them, transforming some abandoned Catholic churches into mosques and community centers. Not far from the Debs Hall, a Spanish-speaking enclave has taken root, climate refugees from Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Rita. The bones of the walkable city have not been obliterated. Housing is typically two-story, two-family wood-frame residences, ‘the Buffalo double’ in the vernacular, like my grandfather built a bit farther east in 1924; or the lower profile, extended ‘telescope cottage’. Until the pandemic-fueled real estate price boom, a house could be had here for $25,000 to $50,000, often less. Residential lots tend to be long and narrow, and as in every poor urban district I know, what people call ‘good blocks’ might be a cross-walk away from blight; ‘good houses’, alongside vacant or tumble-down properties; side streets intact with contiguous houses whose owners are trying, bracketed on each end by broad stretches of near-nothingness – the radial commercial streets that lead downtown and are mute testimony that for sixteen years the city’s first black mayor, incumbent Byron Brown, has not tried very hard for what is considered the black side of town.

Supporters of his challenger, India Walton, pointed out that the mayor’s enthusiasm for bulldozing vacant buildings was excessive (his five-year plan of ‘a thousand a year’ ultimately totaled 8,000); in any case, it had no second act beyond some incongruous suburban-style housing here and there. The city’s poverty rate – about 30 percent, persistent across his tenure – is most starkly visible on the East Side (though hardly unique to it). Among black city residents the rate is 35 percent, three points higher than their rate of home ownership. A stinging report by the University of Buffalo’s Center for Urban Studies comparing the state of black Buffalo in 1990 and the present, called ‘The Harder We Run’, concludes: ‘Everything changed, but everything remained the same.’ For some of us crossing town on broken pavement or riding laggardly buses, low-boil rage is a familiar emotion.

And yet, and yet …

Man in a wheelchair, on disability, in front of his group home off Broadway: ‘I don’t know about socialism, but I think the mayor’s done a good job. You look at the Medical Campus, it’s beautiful. Look at the waterfront, it’s beautiful.’

Retired housing cop, East Side homeowner: ‘I’ve got nothing against India Walton or her campaign. I’m for the mayor for three reasons: affirmative action (I remember what the police department was like before, okay?); property values (I bought my house fifteen years ago for $30,000, someone offered me $170,000 the other day, that’s $140,000 of wealth); and the waterfront (I mean, it’s beautiful).’

Less than two miles from the Debs Hall, the university’s Medical Campus and the expansion of hospitals and other medical facilities have generated jobs, optimism and angry battles over displacement and disrespect in the nearest, largely black residential community. On Main Street and its downtown environs, long-abandoned hotels, department stores and office buildings have been repurposed or are in the process, with apartments priced and designed mainly to attract a niche public: empty-nesters sick of their suburban baggage, young professionals attracted to the city’s craft beer and arts scene, medical workers and students, a few pro football players, notable because they’ve long been associated with suburban residency. The transformation is by turns welcome and aggravating: welcome because no one yearns for the time when a plastic bag blowing across Main Street could symbolize downtown; aggravating because of the revivalists’ apparent contentment with the clichés of inequity. Years of official rhetoric notwithstanding, there remains the reality of the child growing up in a landscape of destitution, crossing over to one of increasing plenty. Farther west on the lakefront, the Canal district offers the city a glimpse of its long-obscured Erie Canal history along with myriad pass-times. The Outer Harbor is for now a relatively unspoiled stretch of nature trails, parkland, marina and beach where on any given summer weekend Buffalo shows up in rainbow streaks: women in plaid shirts and cutoffs towing boats from the water, latin families grilling skirt steak, mixed couples kissing, black elders watching the sun set from folding chairs, women swathed in black reclining under trees with their children.

All of this development has been accomplished with public money on what in large part was or is public land. ‘Socialism for the rich’, Walton’s supporters sometimes said breezily. The bon mot is inadequate when socialism for everyone is ill defined; it seemed especially counterproductive here, given its note of derision in a political context where ‘socialism’ was deployed most often only to deride.

What the phrase discounted, grievously, was not only the full experience of people and place but also the shape-shifting emotional aspect of urban life, the feeling for the city, which doesn’t resolve the contradiction represented by the man in the wheelchair exalting the nice new things while foot-padding along a street deprived of any of them, but does help explain it. ‘I’m Josh’, he said twice to be sure I remembered his name. His friend Marcus was more critical of the incumbent mayor but similarly admiring of the waterfront. What their expressed pride tacitly acknowledged was a sense of ownership: the lake as ‘the wealth of the people’, in Chris Hawley’s phrase, once befouled, effectively privatized by steelworks, now recovered as a zone of pleasure.

Disconcertingly, this store of collective wealth did not figure much in anyone’s electioneering – even though grass-roots action had been critical in determining the shape of the waterfront’s recovery as a public asset; and developers, who’ve already taken their bites, are perched to take more and ruin it.

Kelly, campaign volunteer for Brown, middle-aged: ‘A free for all, that’s what I think when I hear the word, just unrealistic … I think some of it is very fair, like universal health care. But it’s undefined; I think enough people when they use the word don’t know what they’re talking about, including me.’

***

A column inch in the Buffalo Morning Express for November 6, 1919, reports that in the steel company town of Lackawanna, just south of the city line, the Socialist ticket’s candidate scored a surprise victory as mayor amidst heavy repression against striking steel workers; his first order of business, ‘re-establish free speech’. Until India Walton’s surprise primary victory, no one remembered John H. Gibbons. Few know anything about Anna Reinstein, whose name graces another library I used as a child, in a town just east of the city line – Anna, a Polish Jew, politically radical, a doctor who came to Buffalo in 1891 and began practicing gynaecology. When she was honoured in 1941 by the Erie County Medical Society for fifty years of practice, a local paper noted: ‘Incidentally, she is the wife of Boris Reinstein, a former Buffalo druggist, now a commissar in Russia.’ Chris Hawley has a photograph of Boris seated at Lenin’s elbow. ‘Incidentally’ is a nice touch. Boris left Buffalo to serve the revolution in 1917, and never returned. Anna was a member of Buffalo’s Communist Party when she was arrested with forty-two other party members in an anti-Red roundup in 1920. When, at the same time, eighty-three mostly immigrant alleged anarchists were arrested on the East Side and in surrounding towns, a left-wing paper ridiculed them for ‘phrase-radicalism’. Confusion about aims and definitions, an undisciplined language, only encouraged a crackdown, it argued. Clarity would unlikely have deterred police raids. The first Red Scare … The second Red Scare … Decoupling words from meaning is a tactic and legacy of hysteria. Anna and Boris’s children climbed the social ladder, the son buying up land and getting into development; they secured her name on the library, but sealed the archive of her letters and papers, which became available only in the 1990s.

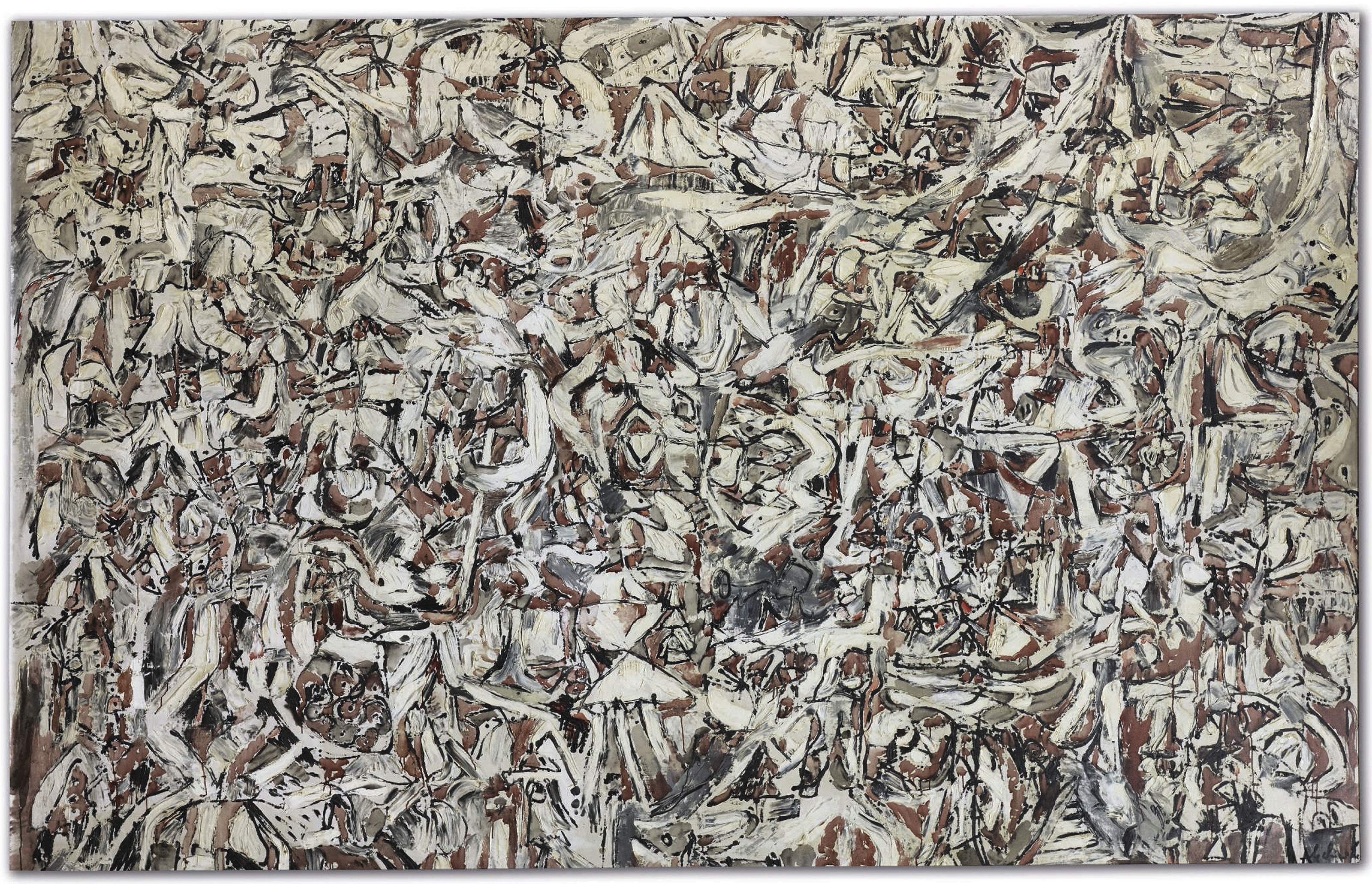

Socialism, in the deceptively mystic serenity of the Eugene V. Debs Hall’s setting, is a reclamation project. Of place, first, and, with it, confidence in the neighbourhood’s future; of social bonds, frayed by post-industrial fragmenting processes; of local labour history for workers largely unmoored from it. The professed goal is to make a social space, a political and cultural space. In conviviality – the exchange of knowledge, the appreciation of experience, the practice of economic cooperation and mutual aid – the class might see itself, and begin to act for itself if only, as a start, through that act of seeing. Much depends on who will be seeing whom, and how.

The hall itself has a spare elegance. A high tin ceiling, a leaded glass transom across big front windows hand-painted with the hall’s name and Debsian red banner, the original dark-panelled wainscoting, the original patinaed bar and tables, a refinished floor which Hawley and friends uncovered from beneath layers of asbestos tile whose evidence is burned into a diamond pattern on the wood, the ghost of ages of spilled beer and dirty mop water seeping through the seams. Above the barback mirror a photograph of Debs is flanked by small black busts of FDR and Marx. Atop the gleaming Art Moderne cash register, a purely decorative effect, sits an unassuming cast iron bust of Debs in his prison clothes.

Try not to get nostalgic, I thought. Balancing past and present is a delicate business, not unique in a city where memory has been a balm against so much loss. ‘Sentimentality is the only reason we exist as a city’, Hawley says. ‘There’s no reason it’s survived except that people love the place.’ That is simultaneously true and not. Love may be a bet on the future, but all bets are not equal.

This part of the East Side, where some people clawed to stay alive and others settled because property was a bargain, is now an area ‘in transition’ because others volunteered to save one remarkable architectural landmark – the Central Terminal, whose 1929 Art Deco tower looms above the grassy flats – and still others have drawn up a redevelopment plan around it. After decades in the dark, the tower now lights up the night sky in dramatic colours. The plan for creating a Civic Commons around it strikes all the right notes until you get to the word ‘destination’. If history is a guide, the commons will be contested. Ironically, but that feels like the wrong word, in his official capacity Chris Hawley authored a new rezoning plan for the city that does not have inclusionary mandates for affordable housing. That was supposed to be worked out by the mayor, he says. ‘Development without displacement’, the cry of poor and working-class residents everywhere, may well be raised within shouting distance of the Debs Hall. Stripped of its disguise as a mark of shame, vacant land is also the wealth of the people.

Alexandria, activist, 19, immigrant from southern Sudan: ‘You know the African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child”; socialism means this to me. Buffalo is the child, and the people are the village who must raise it.’

***

Formally, the Debs Hall is a social club. Unlike taverns, Hawley discovered, non-profit social halls tend to survive their founders; he and the 250 founding members – who each contributed $250 to buy the property and, for that, get $1 off beer for life – take the long view. Membership is $10, ‘open to anyone who has an interest in the labour history of Buffalo or the United States’. There is no political litmus test. Hawley is a member of Democratic Socialists of America, as is India Walton – the plainest explanation for how socialism entered the discourse this political season. An outside wall of the building bears her portrait. (As the only member of city administration who’d backed her publicly, Hawley figured his support ought to be big so that if he were fired that would be big too.) The local DSA chapter meets there, as have the Buffalo Lighthouse Association and neighbourhood koi pond enthusiasts. Any community-based organization can book the hall for free. Walton’s canvassers converged there during the campaign. Volunteer bartenders encourage their networks to come out. Hawley has made presentations around the city about labour history and the hall to groups as obscure as the Greater Western New York Bottle Collectors Association. It is, he says, an explicitly socialist hall (the Connolly Forum in Troy, NY, may be the country’s only other) ‘because the ideas are still relevant … how to empower everyday working people to better their lives collectively.’ But ‘if you look at the old socialist halls, they weren’t sitting around all the time talking about socialism; they were interested in whatever the working class was interested in’.

Segregation, and not just by colour, splinters the nominative singular. It always has. The Walton campaign lost the election (out of inflated fears of socialism, ‘defund the police’ and inexperience), but in spotlighting poverty, land use and uneven development it succeeded in organizing a coalition that crossed barriers of colour, ethnicity, age, income, geography, education, national origin. It did not juice turnout on the East Side or ‘win the working class’, as some have reported, unless one wants to write out most of the city’s unions and all of Brown’s working-class voters, including the firefighters, police and other city workers in historically Irish South Buffalo, which powered his victory. But it felt like something new, as if the ground might be shifting. The Debs Hall is in a majority-white slice of a district that, overall, is 48 percent Asian (mainly Bangladeshi), 24 percent black, 8 percent latin and 13 percent white. Walton lost the district by about 650 votes. Almost 17 percent of the people in that white slice are officially poor, and as in the rest of the district, and the East Side, and the city, or anywhere actually, what it means to be poor is as open for political redefinition as what it means to be a socialist or even working class.

Back when John Gibbons became the region’s first and only Socialist mayor, to be a steel worker meant all the things it means to be poor today: to live always on edge and to die young, your housing substandard, the rent too high for your income, your education inadequate, your psychic and physical environment unhealthy. At the time of the great strike of 1919, steel work meant compulsory twenty-four hour shifts every other day. Organized labourers changed what it meant to be a worker by challenging and ultimately changing factory conditions. Henry Louis Taylor of UB’s Center for Urban Studies argues that the point of attack now is the set of ‘conditions that make some neighbourhoods the factories that produce low-wage workers’: change the conditions and so too what it means to be poor.

People tend not to recognize that workers died to change their conditions, died to ‘bring you the weekend’, as an old union slogan once put it. Maybe because work still leaves them poor, running behind, or because it’s absurd to think ‘dying for the weekend’ might ever have been meant literally. Maybe because, as for so many in this region who are linked by ancestry to vanished industry, death was normalized but collective struggle was not. My father’s father, who built the house not so far from the Labor Lyceum, was a railroad machinist: his lungs gave out in early middle age; his daughter died at 4 of diphtheria; a son was stillborn. I grew up with pictures of the dead, knowing my father assumed responsibility for the family at 17; it didn’t seem weird. My grandmother seemed happy. I think she was: my father became a tool and die maker and didn’t die young, and nor did his wife or his children, and nor did my grandmother, who was never alone. No one talked about historical context.

A century after the heyday of Labor Lyceums, socialism is fetishized, like democracy. As words, like any other, even the most abstract – ‘God’ comes to mind – they are animated only in practice, experience. It would be interesting to observe an election that prompted discussion about democracy. In Buffalo the incumbent mayor, so intimate with cronyism, might have had a problem with that one.

Hawley often begins telling people about Debs the man by saying he was imprisoned in 1920 for giving an anti-war speech and ran for president from behind bars. He begins telling about the Debs project’s first labour history memorial with the story of Casimer Mazurek, a 26-year-old decorated World War I veteran shot to death when Lackawanna Steel guards opened fire on 5,000 men, women and children on a picket line in the opening days of the great steel strike. In both cases, he reports, listeners are amazed. The many whose family histories intersect in some way with steel often know almost nothing beyond that convergence. A plaque, sponsored by the Debs Hall and the Area Labor Federation, sits propped against a wall in the tavern, awaiting deployment. When it is finally erected to commemorate the violence, the failed strike, and the success, twenty-two years later, of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee at Bethlehem Steel, it will be the first public historic marker to recognize the labour history of Western New York.

Lola, university student, political science/pre-law, 19, at a picket line of striking hospital workers: ‘Socialism? It means you’re for the people.’

Jackie, her mother, gift shop manager: ‘I think the word, … I think it’s evolving.’

Read on: JoAnn Wypijewski, ‘Politics of Insecurity’, NLR 103.