Poetry, the American poet Louise Glück once told an audience, a member of whom had, preposterously, asked her to define it, ‘is that which haunts’. The response itself haunts, not least for being strikingly satisfactory. It ‘seems true and deep’, to borrow a phrase of Glück’s, from her essay ‘Death and Absence’. It begins in indeterminacy (‘that which’) and then tapers to a verb (‘haunts’) that is both distinctive and a little mysterious, achieving the air of the irrefutable while ‘loosing a flurry of questions’ (another of Glück’s phrases, this one from her essay ‘Ersatz Thought’). At once distilled and capacious, laconic and expansive, Glück’s definition of poetry shares many of the qualities of her poems.

Glück, who died aged 80 on 13 October, also talked about making poems ‘memorable’. She wrote thirteen collections in all, the first in 1968, the last in 2021, plus two slender books of essays, and a final short ‘fiction’ in prose published last year. She also taught poetry, from her late twenties onward, an experience she found she loved. Teaching was ‘the prescription for lassitude’; interludes of silence, some lasting years, were a feature of Glück’s writing life. Reflecting on working on her students’ poems in her essay ‘Education of a Poet’, she writes: ‘It mattered to get the poem right, to get it memorable, toward which end nothing was held back’. The repetition of ‘get’, producing that subtly odd, almost impatient phrase, ‘get it memorable’, enacts the kind of dogged focus it describes. (Occasionally lines would arrive like gifts, but making poems to house them was generally hard labour: Glück said her last book of poems, Winter Recipes from the Collective, ‘came in the most tortured little drips – I thought of it as rusty water coming out of the tap’.)

The ‘right’ poem, the complete or perfected poem, is the ‘memorable’ one; its raison d’être, to ‘haunt’. Neither claim, similar but not identical, is necessarily obvious. Many poems lend themselves to learning by heart – this is one function, or effect, of rhythm and rhyme – but why would being memorable be the sine qua non? And do we want to be haunted? That which is memorable – one is tempted to say, ‘merely’ memorable – stays with you; that which haunts won’t leave you alone. That which haunts affects, consumes, disquiets, returns unbidden, perhaps unwelcome. And insofar as haunting is often recursive – that which haunts comes back – it isn’t exactly memorable: in fact, we may be haunted by what we would prefer to forget, or are in danger of forgetting (or fear we are: Hamlet’s father’s ghost commands him to ‘Remember me’).

Haunting, then, is not a steady, nor altogether pleasant, voluntary form of persistence. ‘The advantage of poetry over life is that poetry, if it is sharp enough, may last’, Glück once wrote. Her poems are sharp in several senses. They are not only distinguished by clarity, precision and keen intelligence, often delivering a penetrating, sometimes harrowing insight with aphoristic authority (most famously: ‘We look at the world once, in childhood. / The rest is memory.’ – ‘Nostos’). Her poetry is also unsparing, and can be mordant, cutting or frank to the point of callousness. The poems in perhaps her frankest, and most relentlessly morbid collection, Ararat (1990), a kind of family self-portrait written in the aftermath of her father’s death, are studded with barbs, lines of unexpected hostility:

My sister’s like a sun, like a yellow dahlia.

Daggers of gold hair around the face.

‘Yellow Dahlia’

My son’s very graceful; he has perfect balance.

He’s not competitive, like my sister’s daughter.

‘Cousins’

Or almost violent candour:

My mother’s an expert in one thing:

sending people she loves into the other world.

‘Lullaby’

In the same way as she’d prepare for the others

my mother prepared for the child that died.

‘A Precedent’

‘My son’ and ‘my father’ are the only male figures in a collection otherwise dominated by women, including a sister, a ‘girl child’ in Glück’s painful phrase (‘Mount Ararat’), who died before Glück was born. (‘Her death was not my experience, but her absence was’, she reflects in ‘Death and Absence’. It ‘produced in me a profound obligation toward my mother, and a frantic desire to remedy her every distress’ – ‘a haunted child’s compulsive compensation’.)

Ostensibly about death and grief, Ararat is shot through with envy, jealousy, fearfulness, resentment. Poems ‘will not survive on content but through voice. By voice I mean the style of thought’, Glück once wrote, and the ‘style of thought’ – the dominant logic – of the collection is comparison. The speaker often begins by contrasting, likening, ranking, summing up, categorizing. Yet there is usually something awry with these attempts at summary; they seem beside the point, the significance misplaced, a kind of category mistake:

When I saw my father for the last time, we both did the same thing.

‘Terminal Resemblance’

This is a bizarrely roundabout way to begin: that the speaker and her father do the ‘same thing’ is a rather abstract, shallow fact about their final parting (not least because the ‘same thing’ turns out to be waving, hardly an unusual gesture during farewells). By the last stanzas, the opening observation, although outwardly unimpeachable, seems an evasion, a way of not speaking directly of the pain of the memory, much as the speaker’s ‘wave’ is an effort to hide or expel her emotion:

When the taxi came, my parents watched from the front door,

arm in arm, my mother blowing kisses as she always does,

because it frightens her when a hand isn’t being used.

But for a change, my father didn’t just stand there.

This time, he waved.

That’s what I did, at the door to the taxi.

Like him, waved to disguise my hand’s trembling.

Several of the poems in Ararat progress from static abstraction to a painful particular, from some seemingly unflinching summary to a muted emotional climax. Many lead with conclusions: ‘My sister and I reached / the same conclusion: / the best way / to love us was to not / spend time with us.’ (‘Animals’). The second poem in the sequence, ‘A Fantasy’, begins:

I’ll tell you something: every day

people are dying. And that’s just the beginning.

Glück liked poems that dramatize a ‘question, a problem’ in which the ‘poet was not wed to any one outcome’. (In ‘Death and Absence’, she recalls cutting lines that ‘summarized what the poem had to suggest’.) In the light of such preferences, the second sentence in ‘A Fantasy’ sounds almost like a self-referential joke. Glück seems to have set herself the perverse challenge of beginning the poems in Ararat in the most inert way possible, with beginnings that sound like endings, dead-ends (fitting for lyrics that are, after all, about going on after death).

Yet ‘A Fantasy’ doesn’t begin with the pronouncement itself – ‘every day / people are dying’ – but that strangely unprovoked promise of disclosure: ‘I’ll tell you something’ is an odder phrase than its colloquial aspect suggests. The ‘something’ can sound either confiding or a little menacing, either arbitrary (you’ll tell us ‘something’, but will you tell us what we asked, will anything do?) or aggressively pointed. Does the speaker have something to say or is she talking for fear of silence the way her mother compulsively blows kisses? And who would need to be told, who could fail to know, that every day people are dying? Several of the book’s opening lines have this unstable, inscrutable tone: forthright and somehow exposed, knowing and a little childlike, as though the speaker doesn’t quite understand the import of what they’re saying.

‘A Fantasy’ goes on to describe a funeral, but superficially and from a distance, mostly without the specificity that would suggest true intimacy with death:

Then they’re in the cemetery, some of them

for the first time. They’re frightened of crying,

sometimes of not crying. Someone leans over,

tells them what to do next, which might mean

saying a few words, sometimes

throwing dirt in the open grave.

And after that, everyone goes back to the house,

which is suddenly full of visitors.

The widow sits on the couch, very stately,

so people line up to approach her,

sometimes take her hand, sometimes embrace her.

She finds something to say to everybody,

Along with the accumulation of ‘some’ words (‘something’, ‘sometimes’, ‘someone’), the subtle lapses in logic (do people approach the widow because she is sitting ‘very stately’ as that ‘so’ suggests?) are little giveaways, indications that the speaker doesn’t fully comprehend the ‘something’ she set out to tell. It’s as though there is a child hiding within the world-weary manner, with its neat rhymes, or rather it’s the knowing posture that is part of what sounds like a child, a child’s botched precocity. The third and final stanza moves inward – ‘In her heart, she wants them to go away’ – and then ends on a note of unexpected ambivalence. The widow wants to be ‘back in the sickroom’: ‘it’s her only hope, / the wish to move backward. And just a little, / not as far as the marriage, the first kiss.’ She doesn’t want to revive her husband so much as relive his dying; to ‘move backward’ – not quite the same as ‘going back in time’, as though she wants to approach the past but doesn’t want to arrive.

Several of the poems in Ararat ‘move backward’, less advancing toward resolution than unravelling or backtracking from the certainties with which they begin:

Nothing’s sadder than my sister’s grave

unless it’s the grave of my cousin, next to her.

To this day, I can’t bring myself to watch

my aunt and my mother,

though the more I try to escape

seeing their suffering…

‘Mount Ararat’

Despite its sing-song matter-of-factness, the casual briskness of those two symmetrical apostrophes in the first line – among the formal signatures of the sequence – anticipates the speaker’s impulse to hasten past ‘suffering’. She can’t even bring herself to complete the sentence, to name what she can’t watch her aunt and mother do. Yet the second line of the couplet, which ends on that slightly hurried, forced rhyme with ‘sadder’ (‘next to her’), undermines or at least alters the first. The voice of a child is faintly audible, in the ‘unless’, which suggests the speaker searching for the right answer, as though there could be one. There’s the hint of a punchline, too, in the way the second line pulls the rug out from underneath the first by taking its proposition literally – as if it were a genuine invitation to comparison (and isn’t it her sister’s death that’s sadder than her grave?)

*

Escaping suffering – sometimes in the guise of confronting it – is among the major subjects of Ararat. Unlike her ‘brave’ friend ‘able to face unpleasantness’, the speaker is ‘quick to shut my eyes’ (‘Celestial Music’); she shows ‘contempt for emotion’ (‘Paradise’); she is a ‘living expert in silence’ (‘Children Coming Home From School’). The speaker in the sequence is in this sense an unreliable narrator (one poem is titled ‘The Untrustworthy Speaker’), and the drama of the poems arises from the way the language of neutrality, detachment or composure fails to convince. In ‘Cousins’, an amusingly nasty poem, the speaker compares her son to her ‘sister’s daughter’ who is ‘competitive’ (that she won’t say ‘niece’ is an early hint of the speaker’s hostility). But what the poem reveals far more vividly, because implicitly, is the speaker’s own competitiveness, formally disavowed by the even keel of the lines, which can’t quite disguise the tone of jealous vitriol:

Day and night, she’s always practising.

Today, it’s hitting softballs into the copper beech,

retrieving them, hitting them again.

After a while, no one even watches her.

If she were any stronger, the tree would be bald.

The measured pace of each line’s opening clause half-obscures the sound of bitter complaint, capped by that wonderful dry line ‘the tree would be bald’. The flat adjective exudes the venom behind the exaggeration. Next the speaker turns to boasting about her son, with a cloying internal rhyme followed by an almost preening dash: ‘I’ve watched him race: he’s natural, effortless—’. But her son always ‘stops’ – he ‘was born rejecting / the solitude of the victor’. Then follows the deliciously spiteful, socially unacceptable conclusion:

My sister’s daughter doesn’t have that problem.

She may as well be first; she’s already alone.

Reflecting on past efforts to write about her family in ‘Death and Absence’, Glück writes that ‘These poems, these many attempts, were frank but without mystery. The problem was tone… I kept taking appropriate attitudes, when what was wanted had to be, in some way unique’. As with the widow in ‘A Fantasy’, who only wants to go back in time as far as her late husband’s ‘sickroom’, the ending of ‘Cousins’ – feeling viciously competitive toward a child, and seeming to wish them ill – couldn’t be mistaken for an ‘appropriate attitude’. What makes Ararat’s remorselessly frank poems mysterious and unique is this disconcerting tension between sense and sound, between sentence and line, between implied emotion and composed appearance, which scrambles the voice of the speaker.

The speaker’s father is the absent centre of Ararat – ‘there was only one hero. / Now the hero’s dead…there’s no plot without a hero.’ (‘A Novel’). While alive, he appears remote, inexpressive, so much so that he seems to be waiting for death:

What he wanted

was to lie on the couch

with the Times

over his face,

so that death, when it came,

wouldn’t seem a significant change.

‘New World’

He is avoidant, perhaps depressed:

Late December: my father and I

are going to New York, to the circus.

He holds me

on his shoulders in the bitter wind:

scraps of white paper

blow over the railroad ties.

My father liked

to stand like this, to hold me

so he couldn’t see me.

I remember

staring straight ahead

into the world my father saw;

I was learning

to absorb its emptiness,

the heavy snow

not falling, whirling around us.

‘Snow’

The sharp line, the one that punctures the line before – ‘to hold me / so he couldn’t see me’ – brings out the latent desolation in the image of discarded scraps of paper blowing over the railroad ties, two parallel lines that face in the same direction like the child and her father, but never touch, remain permanently separate. ‘So you couldn’t see me’ makes us reconsider the whole first stanza – its scarcely established sense of intimacy and anticipation (‘to New York, to the circus’) – as well as the first mention of holding: ‘He holds me / on his shoulders in the bitter wind’. That line break now seems to foreshadow the winding blow of the later line break – as though the holding is retracted by the fact she is on his shoulders (does being on someone’s shoulders count as being held, or is the child holding the parent – holding on?) And is being on her father’s shoulders the pleasure we assumed it to be or was she too exposed up there to the ‘bitter wind’?

Yet the final verb in the final line – ‘the heavy snow / not falling, whirling around us’ – like the snow itself, ‘looses a flurry of questions’. Glück uses the word ‘whirl’ twice in her essay ‘Ersatz Thought’ to describe the effect of the implicit or the incomplete in poetry: ‘the unspoken, becomes a focus; ideally, a whirling concentration of questions’; ‘the unsaid’ becomes ‘the centre around which the said whirls’. She also talks about the way the sentence ‘initiates and organizes fields of associations which (in the manner of the void) may continue to circulate indefinitely’. In ‘Snow’, even as it could suggest a kind of frightening chaos, ‘whirling’ also revives the air of magic and excitement that opened the poem, and the possibility of wresting poetry from desolation.

Whirling concentrations, flurries of questions, indefinite circulation: this is the sort of poetic permanence – alive, ongoing – Glück prefers to the more commonplace notion of poems as ‘words inscribed in rock or caught in amber’. What is left out of such ‘images of preservation and fixity’, she explains in ‘Death and Absence’,

is the idea of contact, and contact, of the most intimate sort, is what poetry can accomplish. Poems do not endure as objects but as presences. When you read anything worth remembering, you liberate a human voice; you release into the world again a companion spirit. I read poems to hear that voice. And I write to speak to those I have heard.

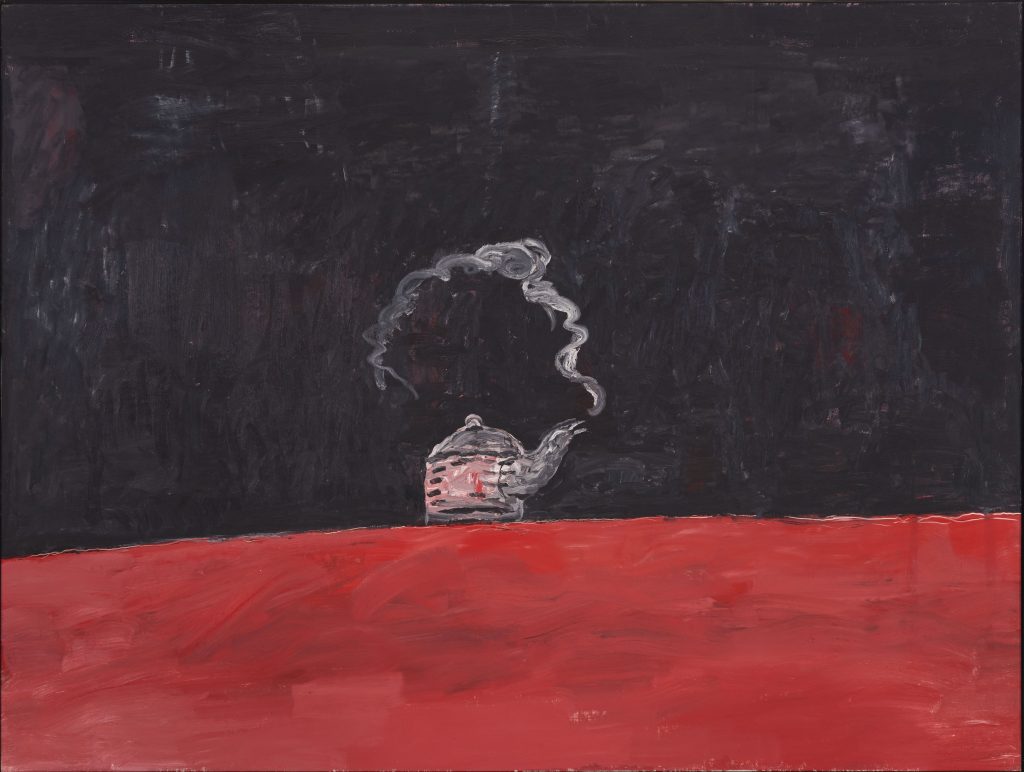

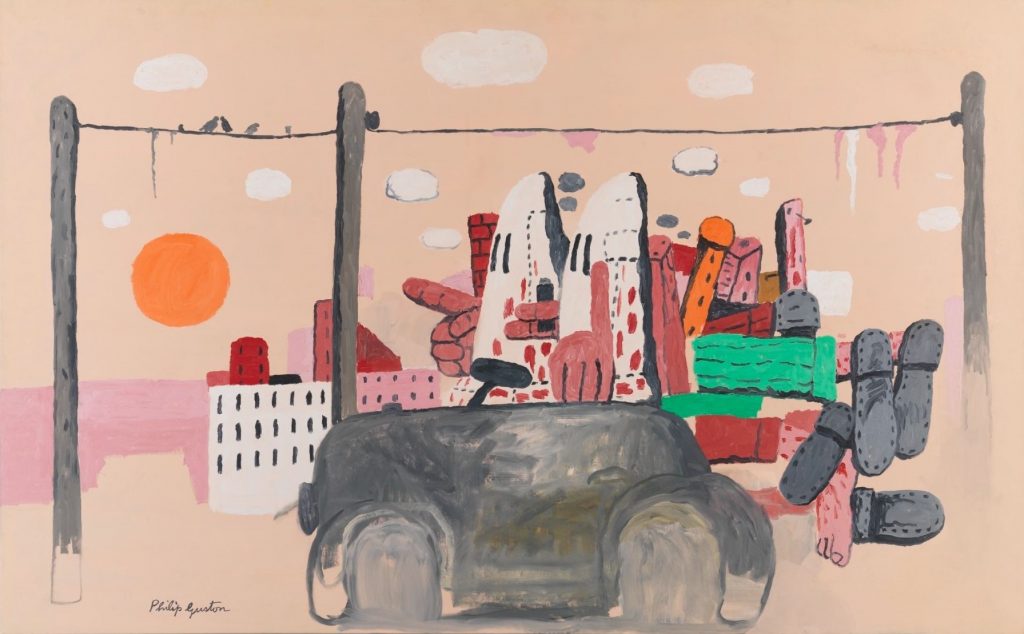

Though they contain their fair share of haunting lines, Glück’s poems are for the most part not, strictly speaking, memorable. They remain ‘strange, and will never become familiar’, as the American painter Philip Guston once said of the work of ‘marvellous artists’. But a poem that endures, this passage suggests, is not ‘memorable’ in the sense of being easy to remember; it is rather ‘worth remembering’. What is worth remembering? That which we are liable to forget, that which we need to continually discover – unsayable feelings and intolerable facts, the ‘unpleasantness’ we are perennially unable to ‘face’.

And that which disappears. ‘It seemed to Marigold that you remembered things because they changed. You didn’t need to remember what was right in front of you’, Glück writes in her final work, Marigold and Rose, a kind of adult-children’s book about the inner lives of infant twins. Marigold is writing a book even though she can’t talk, let alone read, and is given to astonishingly adult – existential, morbid – thoughts: ‘I will be grown up, she thought, and then I will be dead’; ‘the twins knew somehow they were getting older whether they wanted to or not. They would someday walk instead of crawl. They would have teeth…Everything will disappear, Marigold thought.’ Far from being a time of innocence, pre-verbal infancy in Marigold and Rose is a time of concentrated, radical losses of innocence. If ‘we look at the world once, in childhood’, it is then, Glück’s inexplicably convincing swansong suggests, that we absorb the unacceptable fundamentals – nothing lasts, including us and those we love – in elemental form. ‘Everything will disappear. Still, she thought. I know more words now…And both these things would continue happening: everything will disappear but I will know many words.’

What survives is voice, and what distinguishes a ‘specific, identifiable voice’, Glück insisted, is ‘volatility, which gives such voices their paradoxical durability’. It is this volatility which makes a voice seem to speak ‘not from the past but in the present’, which ensures a poem endures not as an ‘object’ but as a ‘presence’. One advantage presences have over objects is that they are not only there; you can be in them. If you read Glück’s poems, you can not only hear her durably volatile voice, you can feel you are in her presence.

Read on: Anahid Nersessian, ‘Notes on Tone’, NLR 142.