If there ever was a question of who is boss in Europe, NATO or the European Union, the war in Ukraine has settled it, at least for the foreseeable future. Once upon a time, Henry Kissinger complained that there was no single phone number on which to call Europe, far too many calls to make to get something done, a far too inconvenient chain of command in need of simplification. Then, after the end of Franco and Salazar, came the southern extension of the EU, with Spain joining NATO in 1982 (Portugal had been a member since 1949), reassuring Kissinger and the United States against both Eurocommunism and a military takeover other than by NATO. Later, in the emerging New World Order after 1990, it was for the EU to absorb most of the member states of the defunct Warsaw Pact, as they were fast-tracked for NATO membership. Stabilizing the new kids on the capitalist block economically and politically, and guiding their nation-building and state-formation, the task of the EU, more or less eagerly accepted, would be to enable them to become part of ‘the West’, as led by the United States in a now unipolar world.

In subsequent years the number of East European countries waiting to be admitted to the EU increased, with the United States lobbying for their admission. With time Albania, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia achieved official candidate status, while Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Moldova are still kept waiting further down the line. Meanwhile enthusiasm among EU member states for enlargement declined, especially in France which preferred and prefers ‘deepening’ over ‘widening’. This was in line with the peculiar French finalité of the ‘ever closer union of the peoples of Europe’: a politically and socially relatively homogeneous compound of states capable collectively of playing an independent, self-determined, ‘sovereign’, above all French-led role in world politics (‘a more independent France in a stronger Europe’, as the just reelected French president likes to put it).

The economic costs of bringing new member states up to European standards, and the required amount of institution-building from the outside, had to be kept manageable, given that the EU was already struggling with persistent economic disparities between its Mediterranean and Northwestern member countries, not to mention the deep attachment of some of the new members in the East to the United States. So, France blocked the entry into the EU of Turkey, a long-standing NATO member (which it will remain even though it has just sent the activist Osman Kavala to prison, for a lifetime in solitary confinement with no possibility of parole). The same holds for several states on the West Balkans, like Albania and North Macedonia, having failed to prevent the accession, in the first wave of Osterweiterung in 2004, of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Hungary. Four years later, Sarkozy and Merkel barred (for the time being) the United States under George Bush the Younger from admitting Georgia and Ukraine into NATO, anticipating that this would have to be followed by their inclusion in the European Union.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine the game changed. Zelensky’s televised address to the assembled heads of EU governments caused a kind of excitement that is much desired but rarely experienced in Brussels, and his demand for full EU membership, tutto e subito, drew unending applause. Overzealous as usual, von der Leyen traveled to Kyiv to hand Zelensky the long questionnaire required to start admission procedures. While normally it takes national governments months if not years to assemble the complex details the questionnaire asks for, Zelensky, Kyiv’s state of siege notwithstanding, promised to finish the job in a matter of weeks, and so he did. It is not yet known what the answers are on questions like the treatment of ethnic and linguistic minorities, above all Russian, or the extent of corruption and the state of democracy, for example the role of the national oligarchs in political parties and in parliament.

If Ukraine is admitted as swiftly as promised, and as its government and that of the United States expect, there will be no longer be any reason to refuse membership not just to the states of the West Balkans but also to Georgia and Moldova, which applied together with Ukraine. In any case, they will all add strength to the anti-Russian-cum-pro-American wing inside the EU, today led by Poland, at the time like Ukraine an eager participant in the ‘coalition of the willing’ assembled by the United States for the purpose of active nation-building in Iraq. As to the EU generally, Ukrainian accession will turn it into even more of a prep school or a holding pen for future NATO members. This is true even if, as part of a potential war settlement, Ukraine may have to be officially declared neutral, preventing it from joining NATO directly. (In fact, since 2014 the Ukrainian army has been rebuilt from scratch under American direction, to the point where in 2021 it effectively achieved what is called ‘interoperability’ in NATO jargon).

In addition to domesticating neophyte members, another job that has come with the EU’s new status as a civil auxiliary of NATO is to devise economic sanctions that hurt the Russian enemy while sparing friends and allies, as much as necessary. NATO controlling the guns, the EU is charged with controlling the ports. Von der Leyen, enthusiastic as always, had let the world know by the end of February that sanctions made in EU would be the most effective ever and would ‘bit by bit, wipe out Russia’s industrial base’ (Stück für Stück die industrielle Basis Russlands abtragen). Perhaps as a German, she had in mind something like a Morgenthau Plan, as proposed by advisers to Franklin D. Roosevelt, in order to reduce defeated Germany to an agricultural society forever. That project was soon dropped, at the latest when the United States realized that they might need (West) Germany for its Cold War ‘containment’ of the Soviet Union.

It is not clear who told von der Leyen not to overdo it, but the abtragen metaphor was not heard again, perhaps because what it implied might have amounted to active participation in the war. In any case, it soon turned out that the Commission, its claims to technocratic fame notwithstanding, failed as badly in planning sanctions as it had in planning macro-economic convergence. In remarkably Eurocentric fashion, the Commission seemed to have forgotten that there are parts of the world that see no reason to join a Western-imposed boycott of Russia; for them, military interventions are nothing unusual, including interventions by the West for the West. Moreover, internally, as push came to shove, the EU found it hard to order its member states what not to buy or sell; calls for Germany and Italy to immediately stop importing Russian gas were ignored, with both governments insisting that national jobs and national prosperity be taken into consideration. Miscalculations abounded even in the financial sphere where, in spite of ever-so-sophisticated sanctions against Russian banks, including Moscow’s central bank, the ruble has recently even risen, by roughly 30 percent between April 6 and April 30.

When kings return, they initiate a purge, to rectify the anomalies that have accumulated during their absence. Old bills are presented anew and collected, lack of loyalty revealed during the King’s absence is punished, disobedient ideas and improper memories are extirpated, and the nooks and crannies of the body politic are cleansed of the political deviants that have in the meantime populated them. Symbolic action of the McCarthy type is helpful as it spreads fear among potential dissenters. Throughout the West today, players of piano or tennis or relativity theory who happen to be from Russia and want to continue playing whatever they play are pressed to make public statements that would make their lives and those of their families back home difficult at best. Investigative journalists discover an abyss of philanthropic donations by Russian oligarchs to music and other festivals, donations that have been welcome in the past but are now found to subvert artistic freedom, unlike of course the philanthropic donations of their Western fellow-oligarchs. Etc.

Against the background of proliferating loyalty oaths, public discourse is reduced to spreading the King’s truth, and nothing but. Putin verstehen – trying to find out about motives and reasons, searching for a clue as to how one might, perhaps, negotiate an end to the bloodshed – is equated with Putin verzeihen, or forgiving; it ‘relativizes’, as the Germans put it, the atrocities of the Russian army by trying to end them with other than military means. According to newly received wisdom, there is only one way of dealing with a madman; thinking about other ways advances his interests and therefore amounts to treason. (I remember teachers in the 1950s who let it be known to the young generation that ‘the only language the Russian understands is the language of the fist’.) Memory management is central: never mention the Minsk Accords (2014 and 2015) between Ukraine, Russia, France and Germany, don’t ask what became of them and why, never mind the platform of negotiated conflict settlement on which Zelensky was elected in 2019 by almost three quarters of Ukrainian voters, and forget the American response by megaphone diplomacy to Russian proposals as late as 2022 for a joint European security system. Above all, never bring up the various American ‘special operations’ of the recent past, like for example in Iraq, and in Fallujah inside Iraq (800 civilian casualties alone in a few days); doing so commits the crime of ‘whataboutism’, which in view of ‘the pictures from Bucha and Mariupol’ is morally out of bounds.

Throughout the West, the politics of imperial reconstruction is targeting anything and anybody found to deviate, or to have deviated in the past, from the American position on Russia and the Soviet Union and on Europe as a whole. It is here that the line is drawn today between Western society and its enemies, between good and evil, a line along which not just the present but also the past needs to be purged. Particular attention is being paid to Germany, the country that has been under American (Kissingerian) suspicion since Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik and the German recognition of the postwar Western border of Poland. Since then, Germany has been suspect in American eyes of wanting to have a voice on national and European security, for the time being within NATO and the European Community, but in the future possibly on its own.

That three decades later Schröder, like Blair, Obama and so many others, monetized his political past after leaving office was as such never a problem. This was different with Schröder’s historical refusal, together with Chirac, to join the American-led posse invading Iraq and, in the act, breach exactly the same international law that is now being breached by Putin. (That Merkel as opposition leader at the time told the world, speaking from Washington DC a few days before the invasion, that Schröder did not represent the true will of the German people may be one of the reasons why she has up to now been spared American attacks for what is claimed to be a major cause of the Ukrainian war, her energy policy having made Germany dependent on Russian natural gas.)

Today, in any case, it is not really Schröder, all-too-obviously inebriated by the millions with which the Russian oligarchs are filling him up, who is the main target of the German purge. Instead it is the SPD as a party – which, according to BILD and the new CDU leader, Friedrich Merz, a businessman with excellent American connections, has always had a Russlandproblem. The role of Grand Inquisitor is robustly performed by the Ukrainian ambassador to Germany, one Andrij Melnyk, self-appointed nemesis in particular of Frank-Walter Steinmeier, now president of the Federal Republic, who is singled out to personify the SPD’s ‘Russian connection’. Steinmeier was from 1999 to 2005 Schröder’s Chief of Staff at the Chancellor’s Office, served two times (2005-2009 and 2013-2017) as Foreign Minister under Merkel, and was for four years (2009-2013) Bundestag opposition leader.

According to Melnyk, an indefatigable twitterer and interview-giver, Steinmeier ‘has for years woven a spider web of contacts with Russia’, one in which ‘many people are entangled who are now calling the shots in the German government’. For Steinmeier, according to Melnyk, ‘the relationship to Russia was and is something fundamental, something sacred, regardless of what happens. Even Russia’s war of aggression doesn’t matter much to him.’ Thus informed, the Ukrainian government declared Steinmeier persona non grata at the last minute, just as he was about to board a train from Warsaw to Kyiv, in the company of the Polish foreign minister and the heads of government of the Baltic states. While the others were allowed to enter Ukraine, Steinmeier had to inform the accompanying journalists that he was not welcome, and return to Germany.

The case of Steinmeier is interesting as it shows how the targets of the purge are being selected. At first glance Steinmeier’s neoliberal-cum-Atlanticist credentials would seem impeccable. Author of Agenda 2010, as head of the Chancellery and coordinator of the German secret services, he allowed the United States to use their German military bases to collect and interrogate prisoners taken from all over the world during the ‘war on terror’ – one can assume in compensation for Schröder’s refusal to join the American adventure in Iraq. He also didn’t make much of a fuss, indeed no fuss at all, when the United States held German citizens of Lebanese and Turkish descent prisoner in Guantanamo, each of whom was arrested, abducted and tortured after being mistaken for somebody else. Accusations that he failed to provide assistance, as he should have done under German law, have followed him to this day.

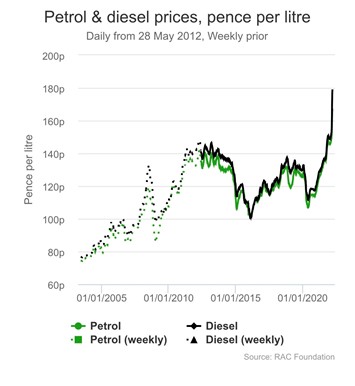

What is true is that Steinmeier helped make Germany dependent on Russian energy, although not quite as charged. It was he who, in 1999, negotiated the German exit from nuclear energy, on behalf of the Red-Green government under Schröder and as demanded, not by the SPD, but by the Greens. Later, as opposition leader, he went along when, after the Fukushima disaster in 2011, Merkel, having reversed nuclear exit I, now reversed again to push through nuclear exit II, ever so cunningly hoping that this would open the door to a coalition with the Greens. A few years later, when she for the same reason ended coal, in particular soft coal, to become effective at about the time of the shutdown of the last remaining nuclear reactors, Steinmeier went along as well. Still, it is he, not Merkel, who is being blamed for German energy dependence on and collaboration with Russia, perhaps out of lasting American gratitude for Merkel’s assistance in the Syrian refugee crisis following the botched American (half-)intervention in Syria. Meanwhile the Greens, the driving force behind German energy policy since Schröder, like the CDU manage to escape American wrath by pivoting to attack the SPD and Scholz for hesitating to deliver ‘heavy weapons’ to Ukraine.

And Nord Stream 2? Here too, Merkel was always in the driver’s seat, not least because the German end of the pipeline was to be in her home state, even her constituency. Note that the pipeline never went into operation, a good deal of the Russian gas that goes to Germany being pumped through a pipeline system that runs in part through Ukraine. What made Nord Stream 2 necessary, in Merkel’s eyes, was the chaotic legal and political situation in Ukraine after 2014, raising the question of how to secure a reliable transit of gas for Germany and Western Europe – a question that Nord Stream 2 would elegantly solve. One doesn’t have to be an Ukraineversteher to understand that this must have annoyed the Ukrainians. It is interesting to note that after more than two months of war Russian gas is still being delivered through Ukrainian pipelines. While the Ukrainian government could shut these down any moment, it does not do so, probably to enable itself and associated oligarchs to continue collecting transit fees. This does not keep Ukraine from demanding that Germany and other countries end their use of Russian gas immediately, in order to no longer finance ‘Putin’s war’.

Again, why Steinmeier and the SPD, rather than Merkel and the CDU, or the Greens? The most important reason may be that in Ukraine, especially on the radical right of the political spectrum, the name Steinmeier is known and hated above all in connection with the so-called ‘Steinmeier formula’ – essentially a sort of roadmap, or to-do-list, for the implementation of the Minsk Accords drawn up by Steinmeier as Foreign Minister under Merkel. While Nord Stream 2 was unforgiveable from a Ukrainian perspective, Minsk was a mortal sin in the eyes not just of the Ukrainian right (among other things, it would have granted autonomy to the Russian-speaking parts of Ukraine) but also of the United States, which had been bypassed by it just as Ukraine was to be bypassed by Nord Stream 2. If the latter was an unfriendly act among business partners, the former was an act of high treason against a temporarily absent king, now back to clean up and take revenge.

As much as the EU has become a subsidiary of NATO, its officials can be assumed to know as little as anybody else about the ultimate war aims of the United States. With the recent visit of the US secretaries of state and defense to Kyiv, it seems that the Americans have moved the goalposts forward, from defending Ukraine against the Russian invasion to permanently weakening the Russian military. To what extent the US have now taken control was forcefully demonstrated when on their trip back to the United States the two secretaries stopped over at the American airbase in Ramstein, Germany, the same that the US used for the war on terror and similar operations. There they met with the defense ministers of no less than forty countries, whom they had ordered to show up to pledge their support for Ukraine and, of course, the United States. Significantly the meeting was not called at NATO headquarters in Brussels, a multinational venue at least formally, but on a military facility which the United States claims to be under its and only its sovereignty, to the muted occasional disagreement of the German government. It was here, the United States presiding under two huge flags, American and Ukrainian, that the Scholz government finally agreed to deliver the long-demanded ‘heavy arms’ to Ukraine, without apparently being allowed a say on the exact purpose for which its tanks and howitzers would be used. (The forty nations agreed to reconvene once every month to figure out what further military equipment Ukraine requires.) One cannot but recall in this context the observation of a retired American diplomat at an early stage of the war that the US was going to fight the Russians ‘to the last Ukrainian’.

As is well-known, the attention span not just of the American public but also of the American foreign-policy establishment is short. Dramatic events inside or outside the United States may critically diminish national interest in a far-away place like Ukraine – not to mention the upcoming midterm elections and the impending campaign of Donald Trump to regain the presidency in 2024. From an American perspective this is not much of a problem because the risks associated with US foreign adventures almost exclusively accrue to the locals; see Afghanistan. All the more important, one would think, for European countries to know what exactly the war aims are of the United States in Ukraine, and how they will be updated as the war continues.

After the Ramstein meeting, the talk was not just of a ‘permanent weakening’ of Russian military power, never mind a peace settlement, but of an outright victory for Ukraine and its allies. This will test the Cold War wisdom that a conventional war against a nuclear power cannot be won. For Europeans the result will be a matter of life and death – which might explain why the German government hesitated for a few weeks to supply Ukraine with arms that could be used, for example, to move onto Russian territory, first perhaps to hit Russian supply lines, later for more. (When the writer of these lines read about the new American aspiration for a ‘victory’ he was for a brief but unforgettable moment hit by a deep feeling of fear.) If Germany had the courage to ask for a say on the American-Ukrainian strategy, nothing like this appears to have been on offer: the German tanks, it seems, will be handed over carte blanche. Rumours have it that the numerous wargames commissioned in recent years from military thinktanks by the American government involving Ukraine, NATO and Russia have one way or other all ended in nuclear Armageddon, at least in Europe.

Certainly, a nuclear ending is not what is being publicly advertised. Instead one hears that the United States assumes that defeating Russia will take many years, with a protracted stand-off, a long-smoldering stalemate in the mud of a land war, neither party being able to move: the Russians because the Ukrainians will unendingly be fed more money and more material, if not manpower, by a newly Americanized ‘West’, the Ukrainians because they are too weak to enter Russia and threaten its capital. For the United States this might appear quite comfortable: a proxy war, with its balance of forces adjusted and re-adjusted by them in line with their changing strategic needs. In fact, when Biden requested in the last days of April another 33 billion dollars of aid to Ukraine for 2022 alone, he suggested that this will be only the beginning of a long-term commitment, as expensive as Afghanistan, but, he said, worth it. Unless, of course, the Russians start firing more of their miracle missiles, unpack their chemical arms and, ultimately, put to use their nuclear arsenal, small battle-field warheads first.

Is there, in spite of all this, a prospect for peace after war, or less ambitious: for a regional security architecture, perhaps after the Americans have lost interest, or Russia feels that it cannot or need not continue the war? A Eurasian settlement, if we want to call it so, will probably presuppose some kind of regime change in Moscow. After what happened, it is hard to imagine Western European leaders publicly expressing confidence in Putin, or a Putinesque successor. At the same time, there are no reasons to believe that the economic sanctions imposed by the United West on Russia will cause a public uprising toppling the Putin regime. In fact, going by the experience of the Allies in the Second World War with the carpet bombing of German cities, sanctions might well have the opposite effect, making people close ranks behind their government.

De-industrializing Russia, à la von der Leyen, will not be possible anyway as China will ultimately not allow it: not least because it needs a functioning Russian state for its New Silk Road project. Popular demands in the West for Putin and his camarilla to stand trial in the International Criminal Court in The Hague will, for these reasons alone, remain unfulfilled. Note in any case that Russia, like the United States, has not signed the treaty establishing the court, thereby securing for its citizens immunity from prosecution. Like Kissinger and Bush Jr., and others in the US, Putin will therefore remain at large until the end of his days, whatever that end will be like. Those European countries that are historically not exactly inclined toward Russophilia, like the Baltic countries and Poland, and certainly also Ukraine, stand a good chance of convincing the public in places like Germany or Scandinavia that trusting Russia can be dangerous to your national health.

A regime change may, however, also be needed in Ukraine. In recent years the ultra-nationalist end of Ukrainian politics, with deep roots in the fascist and indeed pro-Nazi Ukrainian past, seems to have gained strength in a new alliance with ultra-interventionist forces in the United States. One consequence, among others, was the disappearance of Minsk from the Ukrainian political agenda. A prominent exponent of the Ukrainian ultra-right is the Ukrainian ambassador to Germany, mentioned above, who let it be known in an interview with Frankfurter Allgemeine that for him, someone like Navalny was exactly the same as Putin when it comes to Ukraine’s right to exist as a sovereign nation-state. Asked what he would say to his Russian friends, he denied having any, indeed having had any at any time in his life, as Russians are by nature out to extinguish the Ukrainian people.

Melnyk’s political family goes back to the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in the interwar years and under the German occupation, with which its leaders collaborated until they discovered that the Nazis really didn’t distinguish between Russians and Ukrainians when it came to killing and enslaving people. The OUN was led by two men, one Andrij Melnyk (same name as the ambassador) and one Stepan Bandera, the latter to the extent possible somewhat to the right of the former. Both are reported to have committed war crimes under German license, Bandera as police chief, appointed by the Nazis, in Lviv (Lemberg). Later Bandera was pushed aside by the Germans and put under house arrest, like other local fascists elsewhere. (The Nazis didn’t believe in federalism.) After the war, the Soviet Union restored, Bandera moved to Munich, the postwar capital of a host of Eastern European collaborators, among them the Croatian Ustasha. There he was in 1959 assassinated by a Soviet agent, having been sentenced to death by a Soviet court. Melnyk also ended up in Germany and died in the 1970s in a hospital in Cologne.

Today’s Melnyk calls Bandera his ‘hero’. In 2015, shortly after being appointed ambassador, he visited his grave in Munich where he laid down flowers, reporting on the visit on Twitter. This drew a formal reproach from the German foreign ministry, headed at the time by none other than Steinmeier. Melnyk also came out publicly in support of the so-called Azov Battalion, an armed paramilitary group in Ukraine, founded in 2014, which is generally considered the military branch of the country’s several neofascist movements. It is not quite clear to the non-specialist how much influence Melnyk’s political current has in the government of Ukraine today. There certainly are also other currents in the governing coalition; whether their influence will further decline or, to the contrary, increase as the war drags on appears hard to predict at this point. Nationalist movements sometimes dream of a nation rising out of the death on the battlefield of the best of its sons, a new or resurrected nation welded together by heroic sacrifice. To the extent that Ukraine is governed by political forces of this kind, supported from the outside by a United States eager to let the Ukrainian war last, it is hard to see how and when the bloodshed should end, other than by the enemy either capitulating or reaching for his nuclear gun.

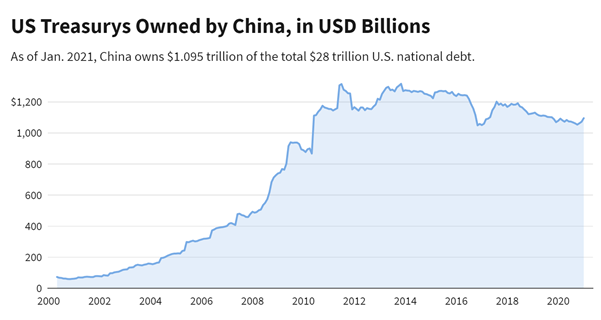

Ukrainian politics apart, an American proxy war for Ukraine may force Russia into a close relationship of dependence on Beijing, securing China a captive Eurasian ally and giving it assured access to Russian resources, at bargain prices as the West would no longer compete for them. Russia, in turn, could benefit from Chinese technology, to the extent that it would be made available. At first glance, an alliance like this might appear to be contrary to the geostrategic interests of the United States. It would, however, come with an equally close, and equally asymmetrical, American-dominated alliance between the United States and Western Europe, one that would keep Germany under control and suppress French aspirations for ‘European sovereignty’. Very likely, what Europe can deliver to the United States would exceed what Russia can deliver to China, so that a loss of Russia to China would be more than compensated by the gains from a tightening of American hegemony over Western Europe. A proxy war in Ukraine could thus be attractive to a United States seeking to build a global alliance for its imminent battle with China over the next New World Order, monopolar or bipolar in old or new ways, to be fought out in coming years, after the end of the end of history.

Read on: Tony Wood, ‘Matrix of War’, NLR 133/134.