In May 2020, the radio station France Inter commissioned a series of prominent writers to reflect on the consequences of the pandemic. One of the first invitees was Michel Houellebecq, reporting on the home front while holed up in his Paris apartment. The tenor of most other interventions was one of hopeful transition, that COVID would mark a civilizational watershed, leaving behind a world indelibly changed. Houellebecq disagreed violently: ‘After lockdown we will not wake up in a new world; it will be the same one, just a bit worse.’ COVID was ‘a banal virus, unglamorously related to some obscure flu illnesses, with poorly understood survival conditions, unclear characteristics – sometimes benign, sometimes deadly, not even sexually transmissible: in short, a virus without qualities’. This banality appeared crueller still given the response – the ways in which the victims had been hidden, abstracted, dehumanized in past months. In his intervention, Houellebecq wondered until what age elderly patients could ‘be resuscitated and cared for? Seventy, seventy-five, eighty years? It depends, apparently, on which region of the world one lives in; but never has the fact that not everyone’s life has the same value been expressed with such quiet impudence; from a certain age onwards, you are practically already dead.’

Indignation at the contemporary treatment of death, along with empathy for the private suffering of the dying, emerges as the animating force of Houellebecq’s latest novel, Anéantir, which arrived in Francophone bookstores in January. The set-up is as follows: the year is 2026, and Paul Raison is an advisor to his friend Bruno Juge, the Minister of Economy and Finance. Trapped in a tired marriage with Prudence, another senior civil servant at the same ministry, he dreams of one-night stands with Juge’s wife, Evangeline. Presidential elections are underway, and Juge is planning to run on a modernizing platform after delivering a reasonably performing economy for the previous five years. Videos of the minister’s beheading surface online, made with such ingenuity that the department’s specialists find themselves at pains to figure out who composed the clips. A series of mysterious cyberattacks then occur, shutting down traffic in several international ports. At this point though, the novel changes gear, as Paul leaves Paris to visit his father, on life support after suffering a stroke. The homecoming involves his sister Cécile, a loyal Le Pen voter and born again Catholic, now married to an unemployed notary. We also get glimpses of Paul’s mother Suzanne, a conservationist, and his brother, Aurélien, an archivist at the Ministry of Culture married to a displeasing woman named Indy. The novel ends with Paul’s own descent into purgatory after a cancer diagnosis.

‘A political thriller veering into metaphysical meditation’ was the polite summary given by one French critic; another spoke of ‘a book written in the minor key’. Many were less polite. Promoted as both a personal reflection on faith and a world undergoing rapid deglobalization, the novel’s 730 pages suggest a Wagnerite symphony, but Anéantir (‘Annihilation’, though the meaning is closer to the German ‘Vernichten’, literally ‘nothingify’) is closer to a string of sonatas, orchestrated with little sign of editorial interference. While the cyber warfare and broken supply chains of the opening pages conjure the same lure of the contemporary as the Islamist takeover of Soumission (2015) or the périphérique revolt of Sérotonine (2019), these incidents rapidly fade from view as the book suddenly transitions into a hospital memoir, growing more and more claustral, dragging itself from one sonata to the other without ever settling on a unifying theme. We hear Paul’s thoughts on presidents, televisions, vegans, the far right, fantasy films, yet none of this amounts to any clear declaration of intent or desire. The novel simply continues, aimlessly, like a device stuck on shuffle mode, switching from one track to another.

To the habitual houellebecqien, the constitutive elements of Anéantir may feel familiar – reminiscent of the competitive sociability of Extension du domain de la lute (1994), the neurotic professionals of Particules élémentaires (1998), the vaudeville treatment of the art world in La carte et le territoire (2010), the meditations on religious feeling in Soumission (2015), the social upheavals of Sérotonine (2019). But there is an unmistakeable diminution. The novel reads as if it was written compulsively and in haste, the range of themes is remarkably less grand in scope, and the tone is uncharacteristically mellow. Its goals are clear enough: Houellebecq hopes to rescue death from its contemporary dehumanization as exemplified in the state response to the pandemic. This is paired with openly congratulatory portraits of the healthcare workers and general practitioners who helped France weather its plague years (in his acknowledgements, Houellebecq devotes a word of thanks to specialists at a French hospital, who helped him with technical details on medical care). Yet this is not what the novel initially promises, nor what we’ve come to expect from Houellebecq.

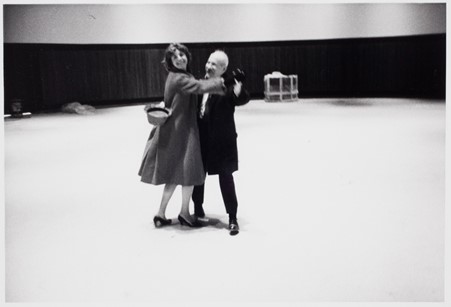

A degree of strategic aimlessness has long been part of his repertoire, and indeed once provided us with Houellebecq at his most exhilarating, whether in the opening party scenes in Extension du domain de la lutte or the closing visits to the psychiatrist in Sérotonine. Such moments approximate the repetitively psalmodic style of Thomas Bernhard, an influence that was made manifest in 2019 when Houellebecq was pictured trying on Bernhard’s jacket during a visit to the late Austrian author’s country estate. The admixture of personal and political also has precedent: Soumission simultaneously dwells on the religious and existential concerns of its protagonist, Sérotonine their depression and ailing sex life. Yet in Anéantir, the balance has shifted, with its long flight of interiority taking Houellebecq’s writing closer and closer to Bernhardian monologue. Bernhard, however, was consistent in his refusal to engage in conventional storytelling. ‘Whenever signs of a story begin to form somewhere, or even when I just see in the distance, behind a prose-hill, the indication of a story emerging, I shoot it down.’ The resulting oeuvre was one in a dizzying state of mid-air suspension, castigated by Baudrillard as little more than onanism for the Viennese bourgeoisie, but consistently captivating in its own right. In Anéantir, however, we have stretches of writing which could only be described as ‘animatronic’, intimating a sense of style where there is, in fact, none:

It was still rather vague but you could feel the beginning of spring, there was a sweetness in the air and the vegetation felt it, the leaves were shedding their winter protection with a quiet shamelessness, they were showing off their tender areas and they were taking a risk, these young leaves, a sudden frost could at any moment destroy them.

Or:

He began to wonder whether he would have been better off coming by car; it was a pleasant surprise to discover that there was a car park in the courtyard of the hospital. Its brightly coloured facade reminded him a little of the one at Saint-Luc Hospital in Lyon. After the PET-Scan, the prospect of a spinal tap and a gastrostomy, this façade. Decidedly, he thought with a mixture of ambiguous feelings, he was increasingly following in his father’s footsteps.

In a passing assessment from 2004, Perry Anderson noted how ‘the steady drone of flat, slack sentences’ in Houellebecq’s work ‘reproduces the demoralised world they depict’. Here even the affect is missing, flatness without its imitative correlative. What might explain such passages? One factor may be that Houellebecq, far from a natural born member of the establishment, has gradually developed a proximity – a cosiness, even – with parts of the French power elite. France, beholden to its republican heritage, is unique in the close relation between its literary stars and political class, consecrated through institutions such as the Académie. The Charlie Hebdo killings of 2015 marked a point of escalation: Houellebecq featured on the cover during the week of the shootings and Soumission was released the same day, with the murders prompting a rallying round of the French establishment in the name of free speech. New Philosophers such as Alain Finkielkraut subsequently celebrated the book as an authentic portrayal of France’s impending ‘Lebanonization’. The effect has been an inevitable weakening of his oppositional stance.

This proximity is encapsulated by the fact that the minister and presidential candidate in the novel is based on Bruno Le Maire, current Minister of Economy and Finance and personal friend of Houellebecq. They first met when the latter’s dog was held up by Irish customs and help from the diplomatic service was required. The two have been exchanging emails ever since about ‘German Romanticism, economic affairs, and Rilke’s poems.’ Anéantir bears unfortunate traces of this friendship. In a recent debate with Éric Zemmour, Le Maire claimed that France was now ‘nearing a growth and employment rate equal to that of the trente glorieuses’. Houellebecq picks up this theme in the book, claiming that the ingoing president was able to restore France’s competitive edge by recharging the nation’s ‘knowledge economy’. The very same ‘knowledge economy’ was once the bane of the French working class in his novels, and these passages could perhaps be read as ridiculing Macron’s attempt to modernize a hopelessly declining country. Yet in the run-up to the last election Houellebecq confessed that, given his recent change of station, he ‘now obviously supports Macron’. Such are the dangers of a writer immune to self-theorization.

In Anéantir this inability for introspection is compounded by an even more destabilizing development. The central subject of Houellebecq’s original novels – the nihilist neoliberalism of the 1990s and 2000s – has become less reliable as a target. As a raw capitalist reflex, neoliberal policies will retain their attraction. But they are hardly election winners anymore, as the current contest in France makes plain. Macron and Le Maire might be Europe’s ‘last neoliberals’, yet they are operating in a landscape far removed from that which the first neoliberals had to navigate. Along with a return to religion, Houellebecq had long predicted that neoliberals might one day adopt the protectionist platforms of their opponents. Yet what to do when the ‘entrepreneurs of the self’ of the 1990s become the ‘zombie Catholics’ of today? The great portraitist of the neoliberal subject has lost his model; in the resulting confusion, the natural pivot is to existentialist cliché: death, faith, Jacob wrestling with the angel, love eternal and so on.

‘Every writer knows the temptation of irresponsibility’, as Sartre used to say. And there has always been a place for smaller feelings in Houellebecq’s work, much as Schopenhauer’s practical philosophy – a source of lasting inspiration to the novelist – ended in unconditional devotion to his poodle. But it is grating to see a writer once antinomic to the ruling order now appear essentially subdued by it. The unrelentingly bleak vision of French life in Houellebecq’s finest novels, which tied together the personal and social dimensions of despair, seemed to implicitly ratify almost any anti-establishment movement (though never openly supportive of the Gilets Jaunes, it appeared that they had a shared object of critique). The characters in Anéantir however do not appear as the resigned victims of neoliberal restructuring. Rather, we see men and women outside of history, facing a godless universe as Christians without a church. The novel may reference nearly every contemporary political orientation – from right-identitarians to anarcho-primitivists to deep ecologists – but all appear merely as unwitting agents in a ‘gigantic collapse’, a naturalised disaster personified by Paul’s father’s comatose state. In this way, Anéantir is more Blaise Pascal than Michel Clouscard, the protagonist (Paul Raison) merely a cipher for modern man’s incapacity to face up to the transcendental.

If this is indeed Houellebecq’s last novel, as he proclaims in the acknowledgements, it is an underwhelming finale. Incensed as he may be by the indignities of the dying, he has remarkably little to say about the causes or material circumstances of their suffering. The pandemic is ultimately just an avenue for his growing spiritual preoccupations, increasingly detached from brutalities of the social. Houellebecq was once able to write compassionately without succumbing to religious delirium. In a 1993 essay on the city of Calais, for instance, composed after the French vote on the Maastricht Treaty, he gave readers a portrait of a déclassé France filled with spleen and anger at its tormentors, but also deeply admiring of its victims:

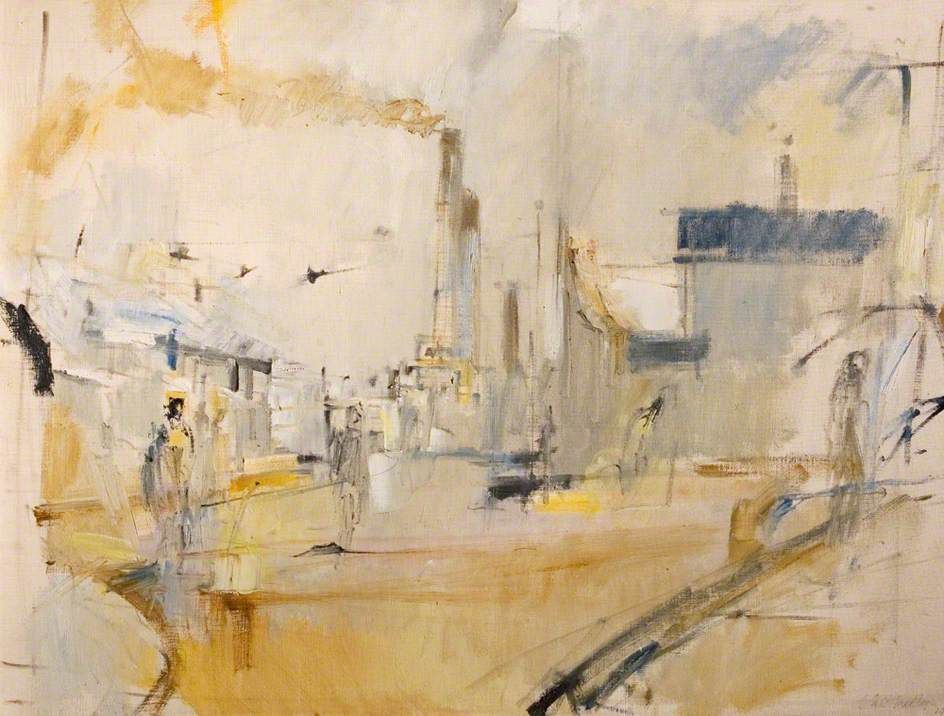

Calais is an impressive city…even if it was razed to the ground during the Second World War. Saturday afternoon one does not see a soul on the street. One passes by abandoned store windows, immense deserted parking spots (without doubt this is the city with the most parking space in the whole of France). Saturday evening is a bit jollier, but it is a particular kind of jolliness: everyone is inebriated. In bars one finds a casino, with a set of machines at which the Calaisians come to waste their benefit payments. The preferred walking spot Sunday afternoon is the entry tunnel to the Manche. Behind the bars, families pushing baby carriages watch the Eurostar pass by. They handwave to the foreman, who hoots in response before being swallowed up by the sea.

Christopher Prendergast, ‘Negotiating World Literature’, NLR 8.