In the first two hundred days of 2022, Taylor Swift’s private jet made 170 flights, covering an average distance of 133 miles. It emitted 8,293 tonnes of carbon dioxide in the process. By way of comparison, the average annual carbon footprint for a US citizen is 14.2 tonnes. In Europe it is 6.8, in Africa 1.04. Swift’s jet, in other words, has a carbon footprint equal to 1,603 Americans, 2,225 Europeans and 14,552 Africans.

None of us would consider taking a plane to travel 133 miles. But evidently, we live in a world apart from the likes of Kylie Jenner – sister of Kim Kardashian – who is apparently partial to taking 12 minute flights. One wonders about the mental processes that govern such decisions, or those that led her to post on Instagram a black-and-white photograph of herself and her partner kissing in front of two private jets, captioned: ‘You wanna take mine or yours?’ It’s dispiriting to see that their uncertainty is seemingly no different from that of children deciding which scooter to ride. But the 7 million plus people who liked the post – evidently dreaming of owning a pair of jets themselves – inspire even more despair.

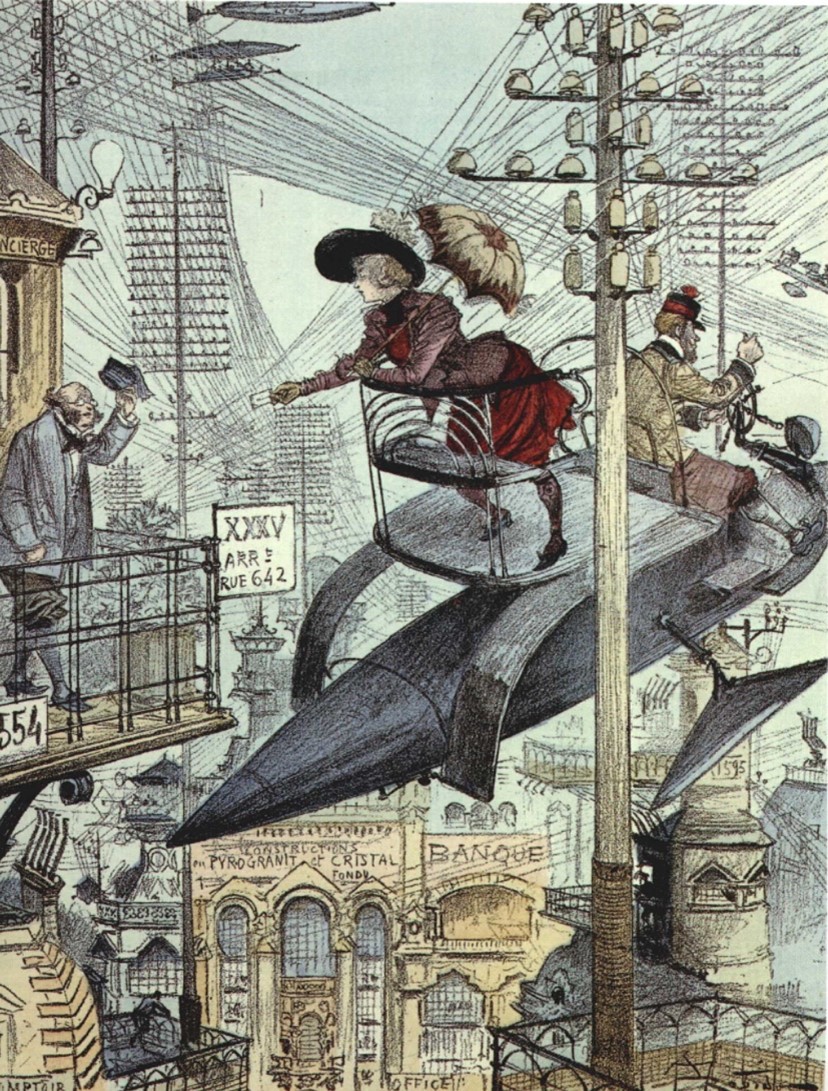

The dream of everyone having their own private aircraft – every man an Icarus – has been a figment of the Western imagination since before air travel even existed. See, for example, this French illustration from 1890 of a graceful lady with hat and parasol on her flying taxi-carriage:

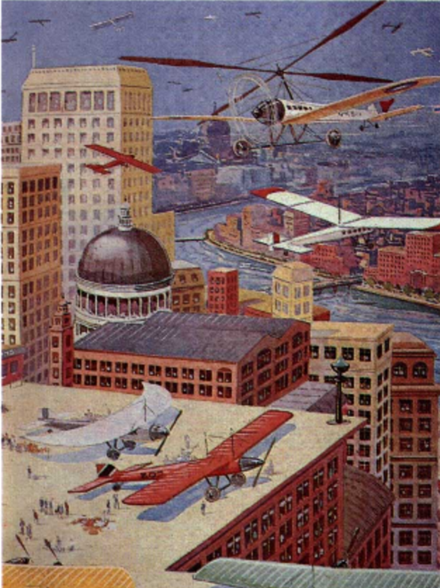

Just as the carriage, once the preserve of ‘gentlemen’, became available to all classes once it was mechanical and motor-powered, so too the aeroplane would one day become a personal form of travel, whizzing along the boulevards of the sky. An American illustration from 1931 already exhibited the idea of city parking for planes, even suggesting, perhaps in keeping with the ineffable Jenner, that a family may possess a number of them, just as they own multiple cars.

An unsustainable utopia: imagine a world with a few billion aircraft whirling around the sky. A few billion cars are already unbearable for the planet. But of course, it is the rarity of aircraft that makes them so desirable. There are 23,241 private jets in operation worldwide (as of August 2022), 63% of which are registered in North America. (The number of private aircraft as a whole is much greater; there are still 90,000 Pipers in operation, plus several other brands of private propeller planes).

Orders for new private jets are on the rise, even as calls to reduce CO2 emissions intensify. Beyond the opulent lifestyles of starlets and ephemeral idols, it is major corporations that are leading the charge. An Airbus Corporate Jet study found that 65% of the companies they interviewed now use private jets regularly for business. The pandemic caused this figure to skyrocket. Last year saw the highest jet sales on record. As one commentator noted: ‘According to the business aviation data firm WingX, the number of flights on business aircraft across the globe rose by 10% last year compared to 2021 – 14% higher than pre-pandemic levels in 2019. The report lists more than 5.5 million business aircraft flights in 2022 – more than 50% higher than in 2020’.

While solemn international summits make plans for reducing emissions (along with the use of plastic, noxious chemicals and so on), elites are polluting away as if there were no tomorrow. Meanwhile, the poor fools down below busy themselves with sorting out their recycling. For our rulers, the question of whether it would be better to have an egg today or a chicken tomorrow is entirely rhetorical. Never in human history has a king, emperor, statesman or entrepreneur chosen the chicken: it is always and only the egg today, at the cost of exterminating the entire coop.

As Le Monde reports, the five largest oil companies posted ‘an unprecedented $153.5 billion (€143.1 billion) in net profits for 2022. The oil giants are approaching the total figure of $200 billion in adjusted net profit’ (i.e. excluding provisions and exceptional items), of which ‘$59.1 billion in adjusted earnings (+157%) for ExxonMobil (US); $36.5 billion (+134%) for Chevron (US); $27.7 billion (+116%) for BP (UK), despite a net loss of $2.5 billion linked to the Russian context; and $39.9 billion (+107%) for Shell (UK).’ Even the environmentally friendly Norwegian state pension fund, Equinor, will benefit from the bonanza: it posted ‘an adjusted net profit of $59.9 billion at the end of just the first nine months of 2022’.

The announcement of these record profits (which have not been taxed by any government) comes on the back of last year’s much-hyped COP27 conference in Sharm el Sheik, attended by as many as 70 executives from the fossil fuel industry. They will be gathering again for another no doubt portentous summit later this year, presided over by Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, chief executive officer of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. (Naturally, a geopolitical emergency serves as a good excuse to delay the slightest environmental action: war in Ukraine has led even the ecologically-minded Germans to reopen their coal mines. Rather than prompting a shift away from natural gas, the war has sparked a frantic search for more of it. The pandemic likewise led to a vertiginous increase in plastic consumption, and if for a few months it helped reduce the emissions from road and air traffic, it dealt a far more serious blow to public transportation, now viewed with suspicion, as a site of infection and contagion.)

It is as if global elites weren’t just mocking the rest of humanity, but the planet itself – poisoning it with one hand while greenwashing with the other. The Italian oil company Eni has as its symbol a six-legged dog, formerly black, now green, thus assuring us of their environmental bonafides. ‘Investment firms have been capturing trillions of dollars from retail investors, pension funds, and others’, Bloomberg writes,

with promises that the stocks and bonds of big companies can yield tidy returns while also helping to save the planet or make life better for its people. The sale of these investments is now the fastest-growing segment of the global financial-services industry, thanks to marketing built on dire warnings about the climate crisis, wide-scale social unrest, and the pandemic.

Wall Street now rates the environmental and social responsibility of business governance, though Bloomberg rightly points out that ESG scores ‘don’t measure a company’s impact on the earth and society’, but rather ‘gauge the opposite: the potential impact of the world on the company and its shareholders’. That is to say, they are not intended to help protect the environment from the companies, but the companies from the environment. ‘McDonald’s Corp., one of the world’s largest beef purchasers, generated more greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 than Portugal or Hungary, because of the company’s supply chain. McDonald’s produced 54 million tons of emissions that year, an increase of about 7% in four years.’ Yet in 2021 McDonald’s saw its ESG score upgraded, thanks to the ‘company’s environmental practices’.

The elites are fond of dangling a grass-coloured future in front of us – deodorized, disinfected and depolluted thanks to biofuels and electric cars. But to produce sufficient biofuel we’d have to cover the earth with soy plantations, definitively deforesting the planet (not to mention the production of fertilisers, pesticides and agricultural machinery). As for the electric car, whilst it pollutes less than its petrol-powered equivalent when used, it actually creates far more pollution to produce one. According to one professor at ETH Zurich’s Institute of Energy Technology, manufacturing an electric car emits as much CO2 as driving 170,000km in a regular car. And this is before the electric car’s engine is even turned on. As one academic study concluded:

the electric cars appear to involve higher life cycle impacts for acidification, human toxicity, particulate matter, photochemical ozone formation and resource depletion. The main reason for this is the notable environmental burdens of the manufacturing phase, mainly due to toxicological impacts strictly connected with the extraction of precious metals as well as the production of chemicals for battery production.

This is without even counting the fact that the electricity used to drive the car will benefit the environment only if it’s produced by clean and renewable sources. At best, the electric car is a mere palliative: the problem is not so much having billions of non-polluting cars, but producing billions of cars in the first place (in addition to the necessary infrastructure).

The elites are fooling the world, but they’re also fooling themselves. They believe they can poison the planet with impunity but save themselves by escaping to recently-acquired estates in New Zealand, far from all the smog and radiation, or else to Mars or some other extra-terrestrial refuge. Infantile dreams, cartoon utopias. One wonders what right they have to proclaim themselves elites in the first place. In the original French, ‘troupe d’élite’ denoted a superior stratum. The term was popularized in postwar sociology by C. Wright Mills’s Power Elite (1956), essentially as a modern synonym for the classical ‘oligarchy’. After the sixties, it fell out of fashion, until reappearing again in the 1990s.

In The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (1995), Christopher Lasch wrote that what characterized the new elites was their hatred of the vulgar masses:

Middle Americans, as they appear to the makers of educated opinion, are hopelessly shabby, unfashionable, and provincial, ill informed about changes in taste or intellectual trends, addicted to trashy novels of romance and adventure, and stupefied by prolonged exposure to television. They are at once absurd and vaguely menacing.

(Note how the fortunes of the term ‘elite’ have gone hand-in-hand with those of ‘populism’, wielded as a pejorative).

Lasch defined the elite in intellectual terms, thereby opening the way for the problematic concept of the ‘cognitive elite’. The champion of the term was Charles Murray, who together with Richard Herrnstein published The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (1994), a book whose essential claim is that black people are more stupid than white people. (In a subsequent conversation with the New York Times, aided by a significant amount of alcohol, Murray summarised his life’s work as ‘social pornography’.) Its introduction claims that ‘modern societies identify the brightest youths with ever increasing efficiency and then guide them into fairly narrow educational and occupational channels. These channels are increasingly lucrative and influential, leading to the development of a distinct band in the social hierarchy, dubbed the ‘cognitive elite’.

Those who govern today’s world consider themselves part of this enlightened set. The legitimacy of their power is based on their supposed intellectual superiority. This is meritocracy in reverse. Rather than ‘They govern (or dominate) because they are better’, we have ‘They are better because they govern (or dominate)’. Weber had already caught onto this inversion in the early twentieth century:

When a man who is happy compares his position with that of one who is unhappy, he is not content with the fact of his happiness, but desires something more, namely the right to this happiness, the consciousness that he has earned his good fortune, in contrast to the unfortunate One who must equally have earned his misfortune. Our everyday experience proves that there exists just such a need for psychic comfort about the legitimacy or deservedness of one’s happiness, whether this involves political success, superior economic status, bodily health, success in the game of love, or anything else.

Given the social, environmental and geopolitical disasters which we are heading towards at breakneck speed, it is easy to doubt the claims of the elite to cognitive superiority. Yet perhaps it is not so much that they are dim, but rather that they are asleep at the wheel – and accelerating towards the precipice.

P.S. I must confess that before researching this article I did not know of the existence of Taylor Swift and Kylie Jenner: it must be me, rather than the elites, who lives in a world apart.

Translated by Francesco Anselmetti.

Read on: Jacob Emery, ‘Art of the Industrial Trace’, NLR 71.