‘The first man who, having enclosed a piece of land, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society.’ With this celebrated incipit from his Discourse on Inequality (1755), Rousseau reminds us what lies behind the institution of the border, and just how vexed this concept is. There is, first of all, the introduction of a physical discontinuity in space: a line, a wire, a fence, a wall. Then there is a proclamation, an affirmation that what’s on one side of that line is mine. Finally there is society’s acceptance of this assertion: I become the rightful owner of the land when society believes me to be so.

Rousseau thereby captures what history has demonstrated countless times: that a border is not a physical entity but a social construction that divides an inside from an outside – a division that, precisely because it is constructed, is liable to alter, disappear and reappear. Indeed, there is nothing so changeable as the ‘sacred borders of the homeland’. One feels a certain tenderness leafing through the atlases of fifty years ago. Or one is struck by sorrow, as I do whenever I travel between Italy and Austria and think of the hundreds of thousands killed in WWI to move a border that no longer exists; or through Alsace and Lorraine, transferred from the Germanic Holy Roman Empire to France in the late 1600s, then from France to Germany with the War of 1870, and again from Germany to France with WWI. Of course, borders also spring up where there were none before, as in the former Soviet Union. The ongoing war in Ukraine is essentially a border dispute – over Ukraine’s borders and NATO’s borders. Its anachronistic, nineteenth-century flavour is due not only to its brutal pattern of trench warfare, but also to its character as a boundary struggle: one that has now brought the entire planet to the brink of nuclear holocaust.

As a social construction, the boundary is always the (temporary) outcome of power relations. There is a particular metric, almost inhuman in its abstraction, that can be used to measure the violence with which it is drawn. This is straightness. Where borders are sinuous and jagged, every indentation and protrusion tells a centuries- or millennia-old story of rivalry, conflict, compromise, agreement. Where borders are rectilinear, on the other hand, there has usually been no such negotiation between the two parties, but an autocratic diktat expressed in the exactitude of the geometry. An almost straight north–south border runs for thousands of miles between Canada and the US. Straight lines also separate various American states, especially west of the Appalachians, where the previous inhabitants were ignored, the land considered ‘virgin’ and the geographical lines drawn with rulers. Likewise with many African nations, with the division of Papua New Guinea, and with the borders between Syria and Iraq, and Iraq and Saudi Arabia, decided at a desk by two officials, Mark Sykes and François-Georges Picot, tasked with dismembering the dying Ottoman Empire in 1916.

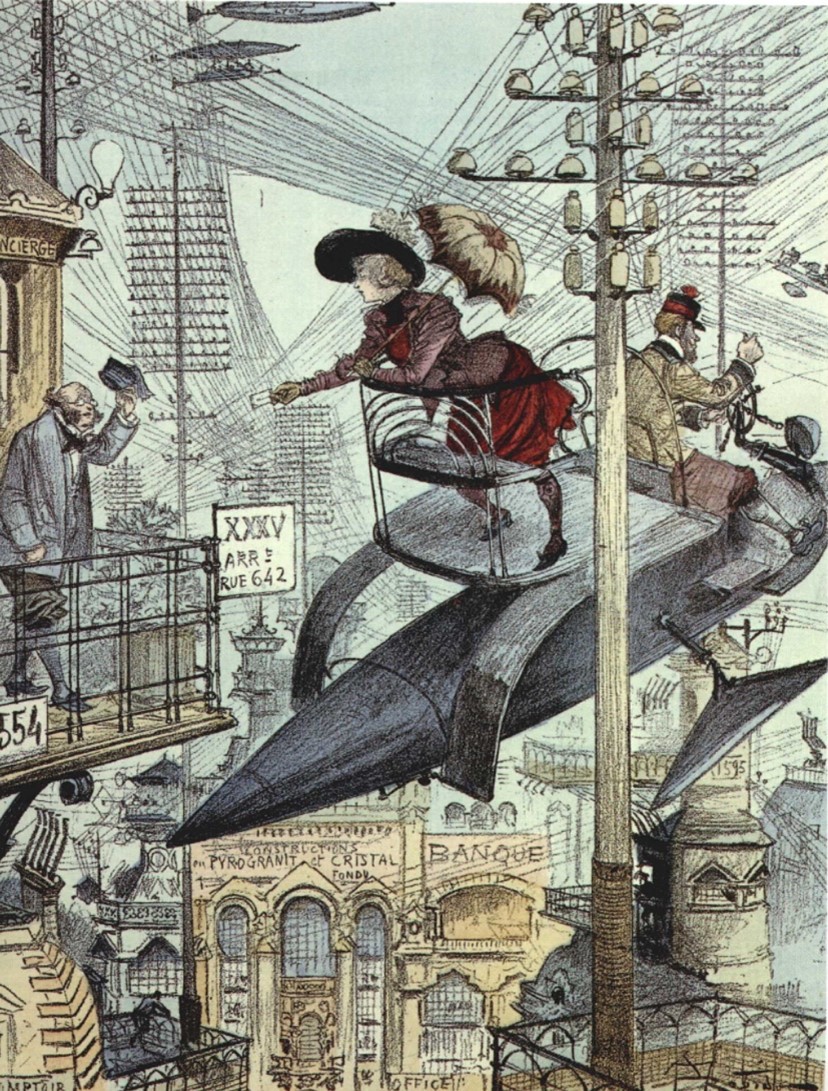

But as borders change, appear and disappear, the border as the founding institution of world geopolitics becomes more and more problematic. It seems paradoxical that in the age of globalization, when the earth appears to us as a small blue planet, when human agency extends under the seas, into space and on the waves of the ether, the problem of borders seems to be more urgent than ever. It was at the end of the 1990s – the ideological apogee of globalization – that the new discipline of Border Studies took shape, giving rise to academic journals, conferences, factions and subdisciplines. At the turn of the millenium, all the trendiest sociologists gravitated towards ‘the border’, whatever their political orientation: Étienne Balibar, Manuel Castells, Saskia Sassen, Ulrich Beck, Zygmunt Bauman. With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the advent of European integration, traditional borders seemed obsolete, yet new forms of delimitation emerged. Thus, Sassen:

One of the features of the current phase of globalization is the fact that a process happens within a territory of a sovereign state does not necessarily mean that it is a national process. Conversely, the national (such as firms, capital, culture) may increasingly be located outside the national territory, for instance, in a foreign country or in digital spaces. This localization of the global, or of the non-national, in national territories, and of the national outside national territories, undermines a key duality running through many of the methods and conceptual frameworks prevalent in the social sciences, that the national and the non-national are mutually exclusive.

This is what Beck calls ‘globalization from within’, whereby borders no longer follow the territorial limits of the nation, but multiply, diversify and become sectorialized. There is no reason why the boundaries of ethnicity, culture or religion should coincide with those of states themselves:

When cultural, political, economic and legal borders are no longer congruent, contradictions open up between the various principles of exclusion. Globalization, understood as pluralization of borders, produces, in other words a legitimation crisis of the national morality of exclusion . . . if the nation-state paradigm of societies is breaking up from the inside, then that leaves a space for the renaissance and renewal of all kinds of cultural, political and religious movements. What has to be understood, above all, is the ethnic globalization paradox. At a time when the world is growing closer together and becoming more cosmopolitan, in which, therefore, the borders and barriers between nations and ethnic groups are being lifted, ethnic identities and divisions are becoming stronger once again.

With the twentieth-century revolutions in transportation, new types of borders cropped up. Airports are an anomaly, since there the border is located not at the edge of the country but within it. One of the UK’s border posts is located in the centre of Paris, at the Gare du Nord from which the Eurostar departs; another can be found in the middle of Brussels. With Covid-19, we saw the creation of temporary borders, such as those that prevented people from entering or leaving China’s vast metropolises. Still, it is interesting to see how confidently the shrewdest social scientists of the time presented globalization as irreversible and, without openly admitting it, situated themselves within the conceptual horizon of the ‘end of history’ – a concept widely mocked but tacitly embraced. Just as they were tracking the rise of ‘globalization from within’, the ultimate cosmopolitanization of human society, deglobalization was already waiting in the wings – ready to erupt with the successive shocks of Brexit, Trump, Covid-19, war in Ukraine and decoupling from China. Meanwhile, the frontiers of yesteryear were getting ready to take their revenge, in the oldest and most mythical fom: that of the wall, like the Vallum Adrianum or the Great Wall of China.

Mind you, barriers had never ceased to be erected – in concrete, latticework, or barbed wire (the list is not exhaustive):

- 1953: a 4 km wall between South and North Korea;

- 1959: 4,057 km of the Line of Actual Control between India and China;

- 1969: 13 km of peace lines in Ireland between Catholic Belfast and Protestant Belfast;

- 1971: a 550 km line of control between India and Pakistan to divide Kashmir;

- 1974: a 300 km green line between Greek and Turkish areas of Cyprus;

- 1989: a 2,720 km Berm between Morocco and Western Sahara;

- 1990: a 8.2 +11 km wall between the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla and Morocco to block migration;

- 1991: a 190 km barrier between Iraq and Kuwait;

- 1994: a 1,000 km Tijuana wall between the US and Mexico.

But globalization has done nothing to curb the walling frenzy; quite the contrary:

- 2003: 482 km between Zimbabwe and Botswana;

- 2007: 700 km between Iran and Pakistan;

- 2010: 230 km between Egypt and Israel;

- 2014: 30 km between Bulgaria and Turkey;

- 2013: 1,800 km between Saudi Arabia and Yemen;

- 2015: 523 km between Hungary and Serbia;

- 2022: 550 km between Lithuania and Belarus;

- 2022: 183 km between Poland and Belarus.

Not to mention naval fortifications to prevent migrants from disembarking by sea. Still, perhaps the country that best exemplifies the level of sophistication – indeed, the level of perversion – that borders have reached, is Israel. This is how Eyel Weizman describes Clinton’s peace plan for the partition of Jerusalem:

64 km of walls would have fragmented the city into two archipelago systems along national lines. Forty bridges and tunnels would have accordingly woven together these isolated neighborhood-enclaves. Clinton’s principle also meant that some buildings in the Old City would be vertically partitioned between the two states, with the ground floor and the basement being entered from the Muslim Quarter and used by Palestinians shop-owners belonging to the Palestinian state, and the upper floors being entered from the direction of the Jewish Quarter, used by Jews belonging to the Jewish state.

In short, the proposed solution was to create a de facto airport, with the Arrivals and Departures located on two different floors that don’t communicate with one another, each with its own entrance and exit. So the border is not a line on a two-dimensional plane, as it appears on a map, but a dynamic partition in three-dimensional space – one whose complexity can be labyrinthine.

Where such ingenuity has been most striking, however, is in the construction of the 730 km wall separating Jewish settlements from Palestinian lands, which began to be constructed in 2002. Weizmann devotes a chapter of his magnificent Hollow Land (2007) to this wall and its consequences. Since those on each side of the partition must still be able to interact, the problem for Israeli planners is how to reconcile such interaction with isolation. For instance, when it comes to a highway that must serve Israelis and Palestinians,

The road is split down its centre by a high concrete wall, dividing it into separate Israeli and Palestinian lanes. It extends across three bridges and three tunnels before ending in a complex volumetric knot that untangles in mid-air, channelling Israelis and Palestinians separately along different spiralling flyovers that ultimately land them on their respective sides of the Wall. A new way of imagining space has emerged. After fragmenting the surface of the West Bank by walls and other barriers, Israeli planners started attempting to weave it together as two separate but overlapping national geographies – two territorial networks overlapping across the same area in three dimensions, without having to cross or come together.

In the face of such intellectual perversion, we must return to that fabled man who first fenced off a piece of land, and read Rousseau’s reaction to this founding act:

From how many crimes, wars and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes, might not anyone have saved mankind by pulling up the stakes, filling in the ditch, and crying to his fellows, ‘Beware of listening to this imposter; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.’

Read on: Chin-tao Wu, ‘Biennials without Borders’, NLR 57