There is no denying the technological marvels that have resulted from the application of transformers in machine learning. They represent a step-change in a line of technical research that has spent most of its history looking positively deluded, at least to its more sober initiates. On the left, the critical reflex to see this as yet another turn of the neoliberal screw, or to point out the labour and resource extraction that underpin it, falls somewhat flat in the face of a machine that can, at last, interpret natural-language instructions fairly accurately, and fluently turn out text and images in response. Not long ago, such things seemed impossible. The appropriate response to these wonders is not dismissal but dread, and it is perhaps there that we should start, for this magic is overwhelmingly concentrated in the hands of a few often idiosyncratic people at the social apex of an unstable world power. It would obviously be foolhardy to entrust such people with the reified intelligence of humanity at large, but that is where we are.

Here in the UK, tech-addled university managers are currently advocating for overstretched teaching staff to turn to generative AI for the production of teaching materials. More than half of undergraduates are already using the same technology to help them write essays, and various AI platforms are being trialled for the automation of marking. Followed through to their logical conclusion, these developments would amount to a repurposing of the education system as a training process for privately owned machine learning models: students, teachers, lecturers all converted into a kind of outsourced administrator or technician, tending to the learning of a black-boxed ‘intelligence’ that does not belong to them. Given that there is no known way of preventing Large Language Models from ‘hallucinating’ – weaving untruths and absurdities into their output, in ways that can be hard to spot unless one has already done the relevant work oneself – residual maintainers of intellectual standards would then be reduced to the role of providing corrective feedback to machinic drivel.

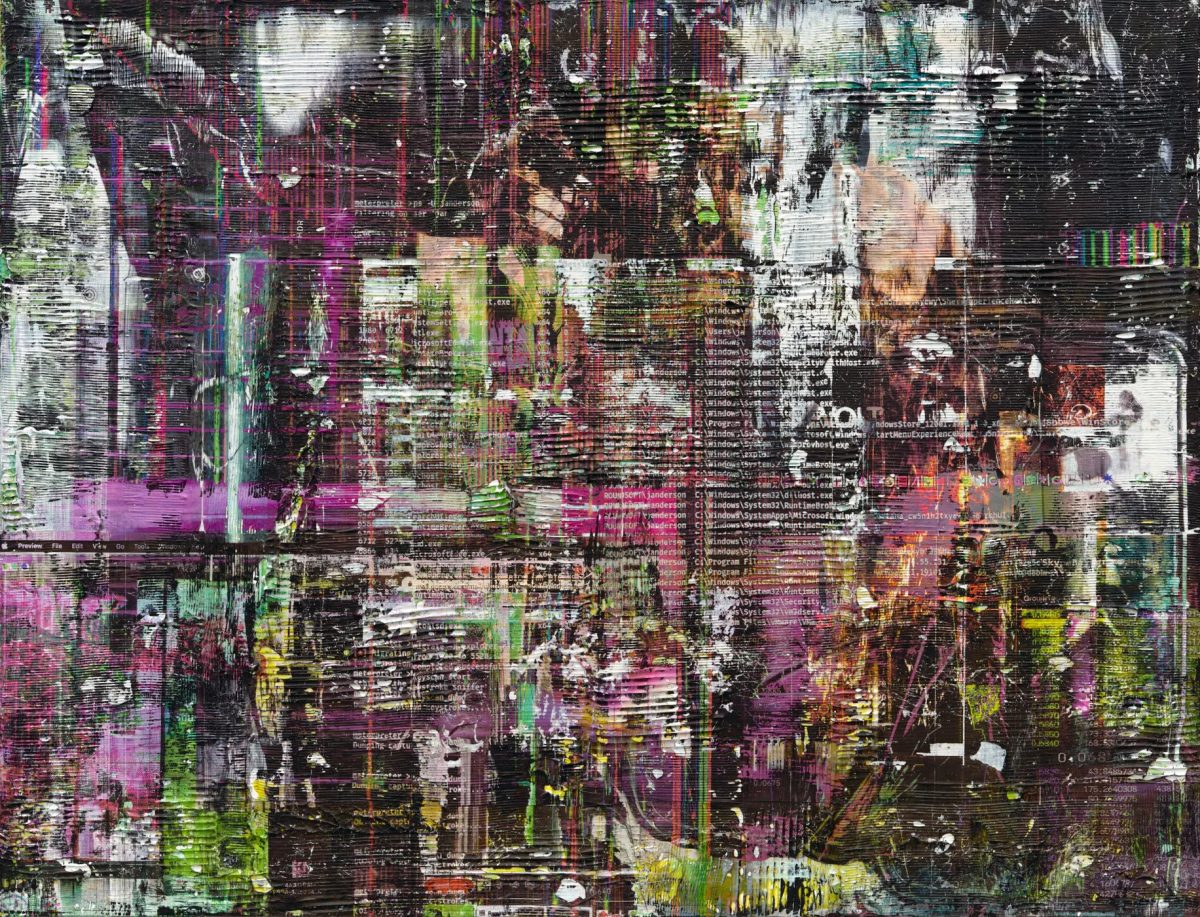

Where people don’t perform this function, the hallucinations will propagate unchecked. Already the web – which was once imagined, on the basis of CERN, as a sort of idealized scientific community – is being swamped by the pratings of statistical systems. Much as physical waste is shipped to the Global South for disposal, digital effluent is being dumped on the global poor: beyond the better-resourced languages, low-quality machine translations of low-quality English language content now dominate the web. This, of course, risks poisoning one of the major wells from which generative AI models have hitherto been drinking, raising the spectre of a degenerative loop analogous to the protein cycles of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease – machine learning turning into its opposite.

Humans, no doubt, will be called upon to correct such tendencies, filtering, correcting and structuring training data for the very processes that are leaving this trail of destruction. But the educator must of course be educated, and with even the book market being saturated with auto-generated rubbish, the culture in which future educators will learn cannot be taken for granted. In a famous passage, the young Marx argued that the process of self-transformation involved in real learning implied a radical transformation in the circumstances of learning. If learning now risks being reduced to a sanity check on the outputs of someone else’s machine, finessing relations of production that are structurally opposed to the learner, the first step towards self-education will have to involve a refusal to participate in this technological roll-out.

While the connectionist AI that underlies these developments has roots that predate even the electronic computer, its ascent is inextricable from the dynamics of a contemporary world raddled by serial crises. An education system that was already threatening to collapse provides fertile ground for the cultivation of a dangerous technology, whether this is driven by desperation, ingenuousness or cynicism on the part of individual actors. Healthcare, where the immediate risks may be even higher, is another domain which the boosters like to present as in-line for an AI-based shake-up. We might perceive in these developments a harbinger of future responses to the climate emergency. Forget about the standard apocalyptic scenarios peddled by the prophets of Artificial General Intelligence; they are a distraction from the disaster that is already upon us.

Matteo Pasquinelli’s recent book, The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence, is probably the most sophisticated attempt so far to construct a critical-theoretical response to these developments. Its title is somewhat inaccurate: there is not much social history here – not in the conventional sense. Indeed, as was the case with Joy Lisi Rankin’s A People’s History of Computing in the United States (2018), it would be hard to construct such a history for a technical realm that has long been largely tucked away in rarefied academic and research environments. The social enters here by way of a theoretical reinterpretation of capitalist history centred on Babbage’s and Marx’s analyses of the labour process, which identifies even in nineteenth century mechanization and division of labour a sort of estrangement of the human intellect. This then lays the basis for an account of the early history of connectionist AI. The ‘eye’ of the title links the automation of pattern recognition to the history of the supervision of work.

If barely a history, the book is structured around a few striking scholarly discoveries that merit serious attention. It is well known that Babbage’s early efforts to automate computation were intimately connected with a political-economic perspective on the division of labour. A more novel perspective here comes from Pasquinelli’s tracing of Marx’s notion of the ‘general intellect’ to Ricardian socialist William Thompson’s 1824 book, An Inquiry into the Principles of the Distribution of Wealth. Thompson’s theory of labour highlighted the knowledge implied even in relatively lowly kinds of work – a knowledge that was appropriated by machines and set against the very people from whom it had been alienated. This set the stage for speculations about the possible economic fallout from this accumulation of technology, such as Marx’s famous ‘fragment on machines’.

But the separating out of a supposed ‘labour aristocracy’ within the workers’ movement made any emphasis on the more mental aspects of work hazardous for cohesion. As the project of Capital matured, Marx thus set aside the general intellect for the collective worker, de-emphasizing knowledge and intellect in favour of a focus on social coordination. In the process, an early theory of the role of knowledge and intellect in mechanization was obscured, and hence required reconstruction from the perspective of the age of the Large Language Model. The implication for us here is that capitalist production always involved an alienation of knowledge; and the mechanization of intelligence was always embedded in the division of labour.

If Pasquinelli stopped there, his book would amount to an interesting manoeuvre on the terrain of Marxology and the history of political economy. But this material provides the theoretical backdrop to a scholarly exploration of the origins of connectionist approaches to machine learning, first in the neuroscience and theories of self-organization of cybernetic thinkers like Warren McCulloch, Walter Pitts and Ross Ashby that formed in the midst of the Second World War and in the immediate post-war, and then in the late-50s emergence, at the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, of Frank Rosenblatt’s ‘perceptron’ – the earliest direct ancestor of contemporary machine learning models. Among the intellectual resources feeding into the development of the perceptron were a controversy between the cyberneticians and Gestalt psychologists on the question of Gestalt perception or pattern recognition; Hayek’s connectionist theory of mind – which he had begun to develop in a little-reported stint as a lab assistant to neuropathologist Constantin Monakow, and which paralleled his economic beliefs; and vectorization methods that had emerged from statistics and psychometrics, with their deep historical links to the eugenics movement. The latter connection has striking resonances in the context of much-publicized concerns over racial and other biases in contemporary AI.

Pasquinelli’s unusual strength here lies in combining a capacity to elaborate the detail of technical and intellectual developments in the early history of AI with an aspiration towards the construction of a broader social theory. Less well-developed is his attempt to tie the perceptron and all that has followed from it to the division of labour, via an emphasis on the automation not of intelligence in general, but of perception – linking this to the work of supervising production. But he may still have a point at the most abstract level, in attempting to ground the alienated intelligence that is currently bulldozing its way through digital media, education systems, healthcare and so on, in a deeper history of the machinic expropriation of an intellectuality that was previously embedded in labour processes from which head-work was an inextricable aspect.

The major difference with the current wave, perhaps, is the social and cultural status of the objects of automation. Where once it was the mindedness of manual labour that found itself embodied in new devices, in a context of stratifications where the intellectuality of such realms was denied, in current machine learning models it is human discourse per se that is objectified in machinery. If the politics of machinery was never neutral, the level of generality that mechanization is now reaching should be ringing alarm bells everywhere: these things cannot safely be entrusted to a narrow group of corporations and technical elites. As long as they are, these tools – however magical they might seem – will be our enemies, and finding alternatives to the dominant paths of technical development will be a pressing matter.

Read on: Hito Steyerl, ‘Common Sensing?’, NLR 144.