Architecture is, along with finance and armaments, one of the few industries in which the United Kingdom punches above its weight; perhaps the more benign of the three. The fact of Britain’s prominence is somewhat counterintuitive, given the notoriously poor quality of the British built environment compared with elsewhere in northwestern Europe, but then this isn’t a matter of actual buildings in this country. It is owed to the global dominance of two largely British-based architectural trends: High-Tech, devised by Archigram, Norman Foster and Richard Rogers in the late sixties; and a more amorphous movement, spearheaded by designers based at the Architectural Association (AA) in Bloomsbury a decade later, such as Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, and occasionally known by its practitioners as Deconstructivism or Parametricism but more usually described through faintly insulting epithets – ‘starchitecture’, ‘signature architecture’, ‘iconic architecture’, ‘oligarchitecture’. Both of these initially distinct movements overcame a difficult 1980s to fuse as a house style for New Labour at home and the ‘emerging markets’ – mainly China and the UAE – abroad. Beneath the famous names – some of whom are dead, and few of whom are much involved today in the buildings that carry their signature – are a plethora of obscure multinationals with roots in Britain that have spent the 21st century quietly designing entire new cities, with the likes of Aedas, Atkins, Benoy or Broadway Malyan working in watered-down versions of the styles of the archicelebrities. The quality of what they do may be questionable, but the profits are substantial.

Throughout the period during which this architecture arose out of its Clerkenwell studios to bestride the globe, there were firms who practised some sort of principled refusal, working quietly and unobtrusively in Britain. The foremost non-players were perhaps Caruso St John, whose work since 1990 is now the subject of Collected Works, a valedictory two-volume set of monographs published by MACK. To see the firm’s major works, you have to go to Nottingham, Walsall or Zurich, rather than Abu Dhabi, Beijing or New York – or, for the most part, London. Adam Caruso is Canadian, trained at McGill in Montreal, and Peter St John is English, from the Surrey-South-West London interzone, trained at the AA. The pair met in London in the 1980s, working first for Florian Beigel, a designer in the Walter Segal tradition of participatory, socialistic building, and then for Arup, the global megacorp that grew out of the London firm established by the Danish engineer Ove Arup in the 1930s; Beigel appears to have become their model for what to do, Arup for what not to. The sparse oeuvre spread across these two slabs of books is, accordingly, devoid of computer-aided geometries, spectacle, giant spans and wild cantilevers; but it also wholly transcends the dull-minded literalness of neoclassicists like Quinlan Terry or Demetri Porphyrios. You can as little imagine a Caruso St John building in Poundbury as you can in Dubai.

To be sure, many of the firm’s virtues are negative ones – the explicit posture of refusal is helpful here. There are contemporaries working in a similar vein – Sergison Bates, Haworth Tompkins or Lynch Architects, for instance – and they can be seen as successors to slightly older designers whose work aims at subtle negotiations between classical and modern, like David Chipperfield or, especially, Tony Fretton. But unlike a superficially similar confrère such as Chipperfield or the German designer Hans Kollhoff, their engagement with classicism has no hint of totalitarian chic. Unlike the occasionally dour work of some of the firm’s London co-thinkers, there is always humour and imagination in Caruso St John’s designs, but in contrast to the similarly perverse but much more successful duo of Herzog and De Meuron, they have never given in to grand ‘iconic’ gestures, as the Swiss duo eventually did in their Hamburg Elbphilharmonie. There is no house style – every project is an event, a unique response to a place and a brief, a process which is, inevitably, expensive and long-winded. Because of this, and because of the delight and surprise their work provokes, they are the only London-based architects whose new work I will almost always make the effort to go and see. This is easy to do, as a major Caruso St John building comes along only once or twice a decade.

Caruso St John, Brick House, from Collected Works: Volume 1 1990-2005 (MACK, 2022). Photograph: Hélène Binet. Courtesy of Caruso St John and MACK.

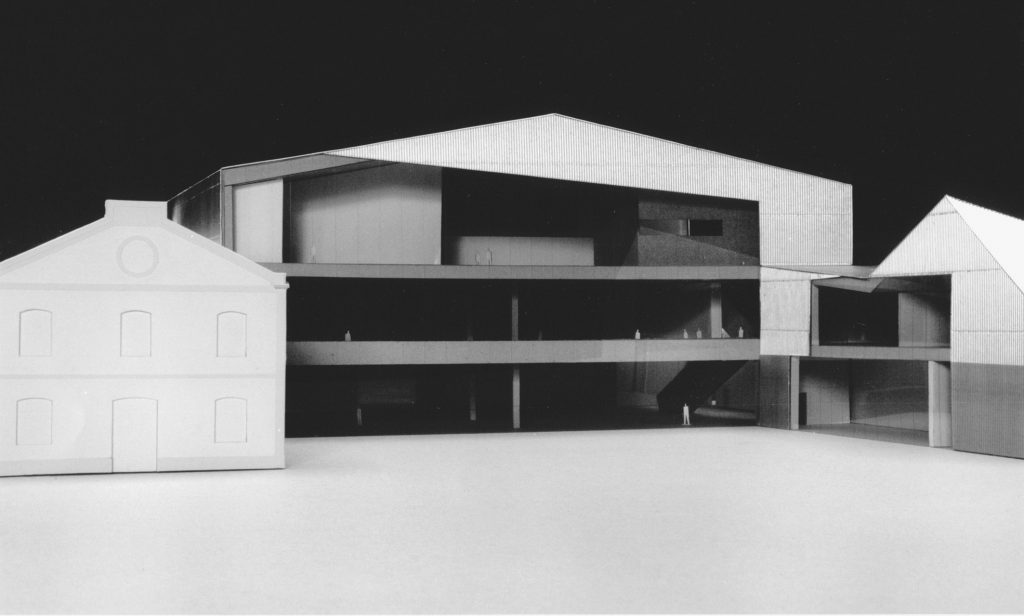

The Collected Works may be sparse in terms of finished buildings, but they are bulked out with ideas. Their built and unbuilt work, interviews, dialogues and contemporary reviews are here placed alongside texts intended as a guide to how the buildings were conceived: a curious bunch, ranging from Eliot’s ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’ and Rosalind Krauss’s ‘The Double Negative’ to a dialogue between Wim Wenders and the young Hans Kollhoff on the gap sites of 1980s Berlin. With these are texts about or written by some of the architects they consider forebears, usually figures who ambiguously straddle modernism and classicism: Sigurd Lewerentz, Louis Sullivan and Ernesto Rogers (but never his nephew Richard). There are long-forgotten early built projects – an exceptionally deadpan doctor’s surgery in the sixties suburbia of Walton-on-Thames, a shed in the Isle of Wight – and there are shadow projects, such as competition entries for contests won by spectacular monuments by a very famous firm, for the London Architecture Foundation, which they note was ‘won by an inexplicable and unbuilt project by Zaha Hadid’; and for Rome’s Centre for Contemporary Arts, where Hadid again won, and would go on to construct an immense flowing mass of precipitous voids and sudden surges. Caruso St John’s proposal was for a giant corrugated iron barn, a hypertrophied version of the industrial buildings already on the site.

Caruso St John, Centre for Contemporary Arts Rome, competition model, from Collected Works. Model photograph: David Grandorge, 1999. Courtesy of Caruso St John and MACK.

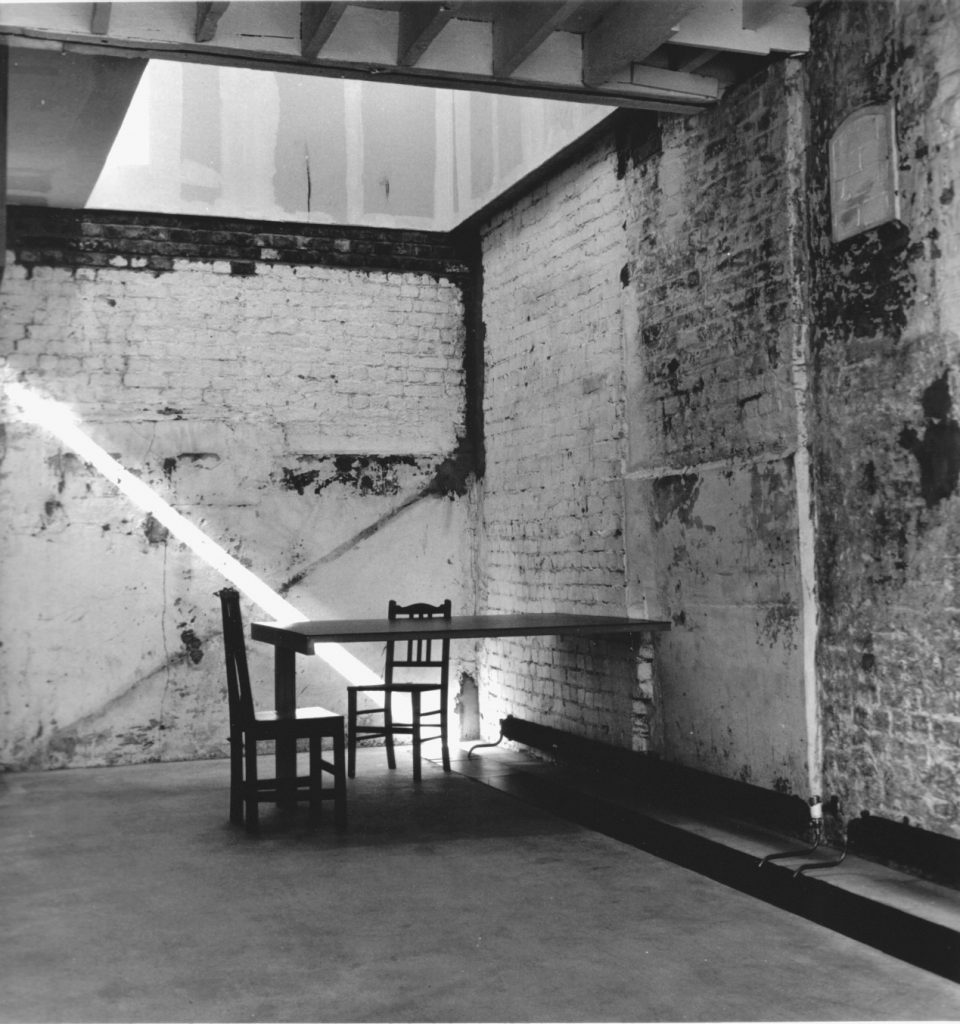

The first volume begins with a combative joint lecture to the AA in 1998. It is aimed against, specifically, the work of Rem Koolhaas and the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), and the notion that ‘if it is to continue to be relevant, the discipline must have a closer knowledge of the workings of the global market economy’, and must perforce design its products – sprawl, luxury housing, airports, malls, infrastructure. This, in the work of OMA, results in ‘an architecture of exaggerated complexity, where bifurcating plates are somehow expressive of optimised programmatic systems and the non-Cartesian space made possible by the new descriptive tools of computing’. That formalism is placed explicitly in the service of neoliberalism, an ideology which the pair describe as ‘yet another abstracted economic model’, which they expect to be proven in time to be every bit as flawed as ‘the Soviet centralised economy’. The placement of this assault at the start of the book is surely a deliberate well, we told you so. Alongside the polemic is the positive programme, which they outline via a series of oblique slides: Robert Smithson’s ‘Spiral Jetty’; the stained sheet metal of a cement works in Rugby; corrugated iron houses in Georgia; accretive brick warehouses in Clerkenwell. They then present Caruso’s own house, built in and around a small, converted abattoir in a Highbury backstreet. Its brick shell has been added to with a perch of MDF and glass; inside is torn seventies wallpaper, dirty brick, bare concrete.

At first, the firm’s position was laid out as being neither neoclassicist, in the banal sense then embraced by British developers and local authorities, nor neomodernist, in the manner of Foster, Rogers, Hadid or Koolhaas. In a late nineties article in High-Tech’s house journal Blueprint, Caruso argued, against the magazine’s raison d’etre, that ‘the hysteria that characterises the creation of new markets and the behaviour of existing ones cannot be financially sustainable and, more seriously, are not environmentally sustainable’. He agrees with Koolhaas that to build for much of the late 20th-century environment is to build for neoliberalism, and therefore the critical act was to refuse to do it. After all, ‘has the percentage of total construction involving architects ever been higher than one per cent?’ So why not drop out? Why not, instead of trying to harness all the madness of the stock market into computer-aided globules and crescendos, ‘put forward ameliorative strategies and paradigms that might suggest what could come after the global market and can remind us of things that are excluded within the current social model’?

Against the metaphors of movement – collapse, explosion, eruption – favoured by Hadid or OMA, Caruso insisted here that, being wholly inanimate, ‘architecture is by definition about stasis’. The photographs the firm favoured as documentation and displayed in their early lectures were also static, laconic, in a Dusseldorf School tradition indebted to Thomas Struth or the Bechers, and tended to depict all the mess around the building that was ostensibly the focus. The odd little perch in Highbury that Caruso and St John showed off to the AA is a case in point, a peculiar found object, and a very London one. The essays and talks collected in the first volume of Collected Works, dating from the mid-1990s, describe London lovingly, outlining something close to the oddly calm city depicted in the series of sustained shots that make up Patrick Keiller’s now-canonical 1994 film, London (the similarity is unsurprising given Keiller and Caruso St John share Beigel as a mentor). Dirty, depopulated and often derelict, defined by the legacies of 19th-century speculation and 20th-century public housing, it is a place to get lost in, irrational and at least partly abandoned by capital. In a 1998 dialogue at the AA, St John explains ‘we’ve always enjoyed the broken fabric and additive character of London, the way it accepts the new amongst the old without too much fuss’.

St John’s 2000 essay ‘London for instance’ depicts the English capital as a fragmentary city seen through odd angles and juxtapositions. Each form has its own value, with the space shared by the terrace, the warehouse and the council estate, all accepted for their distinct qualities: ‘in this openness is space for architects to breathe’. That city is long gone. In a later conversation from 2019, on the approaching thirtieth anniversary of the practice, Caruso remembers this ambiguous city, and cries: ‘it’s much more depressing now!’ Post-industrial London was repopulated and rebuilt after 1997, and ‘most sites have been built on in a very poor way. That development could have been controlled to make something so much better, but this late capitalist laissez-faire is very careless. Damaged urban fabric has a poetic content, and you can do something that is careful and attentive to those qualities’, but the Richard Rogers-inspired preference for ‘brownfield’ development quickly erased nearly all those interestingly empty dream-spaces.

The important buildings by the duo, the work for which I suspect they’ll be remembered, comprise two purpose-built art galleries in the English Midlands – Walsall New Art Gallery, designed in 1995 and opened in 2000, and Nottingham Contemporary, designed in 2004 and opened in 2009. These were for sites similar to those that Caruso and St John described in 1990s London: an apparently unplanned mess of industrial remnants, council housing, stray civic monuments, banal postmodernist retail and developer housing, wasteland, canals, viaducts. Both are highly atypical products of the wave of new arts funding and urban regeneration cash that flowed into post-industrial Britain in the Major and Blair years. After nearly a decade and a half of austerity, one can easily imagine a certain affection developing for New Labour architecture. The best of it – the late Will Alsop’s monumental, cranky Peckham Library, for instance – is now well-loved. But the great majority of this construction was, and is, patronising trash, galumphing into cityscapes in order to brighten and enliven an assumed Northern and Midland misery via lime-green cladding, barcode facades and meaningless giant atria. Most of all, very little of it showed the slightest engagement with what was already there. Indeed, that ignorance was precisely the point – these buildings were meant to launch Gateshead, Barnsley or Middlesbrough out of their depression into a future of creative industries and creative property development. Here, Caruso and St John’s interest in the mundane and ordinary and their scepticism towards the ‘aspirational’ bullshit of neoliberalism meant that they were able to design buildings in post-industrial towns and cities that felt wholly of their place, without ever being tediously ‘in keeping’. Neither of the two Midlands galleries could be imagined anywhere other than exactly where they are.

Caruso St John, View of New Art Gallery Walsall from the south, from Collected

Works. Photograph: Hélène Binet, 2000. Courtesy of Caruso St John and MACK.

Walsall, the earlier of the two, was designed to house the Garman Ryan Collection, a first-rate modern art collection granted to the town in the 1970s and then shoved into a room above the municipal library. So from the outset, rather than offering a shell for an amorphous programme, Caruso St John knew what they were designing for – small-scale, mostly modernist but figurative paintings, drawings and sculpture – and built around that, with the light and views precisely calibrated towards what was inside; and what was around it, with the apparently arbitrary arrangement of windows providing both frontal and oblique views of Victorian civic buildings and canal-side factories, framing your own little Dusseldorf School miniature. The stubby tower that housed the galleries was clad in grey tiles, with a blocky form that seemed designed to be appreciated like the grain silos or coal hoppers of a Bechers photograph. It isn’t all deadpan, and a certain perversity creeps into the detailing, with the same module used for the shuttering imprinted on the concrete and the wood of the stairwells. This love for decoration and paradox would come to the fore in the subsequent gallery in Nottingham. Rather than a flat site by a canal, this is on a steep hill connecting the railway station to the 19th-century Lace Market, between a main road and a tram viaduct. It is, again, rectilinear, slightly box-like, housing big concrete halls for temporary exhibitions; but these stacked forms are scalloped and then incised with a lace pattern.

Caruso St John, Nottingham Contemporary, from Collected Works. Courtesy of Caruso St John and MACK.

This sort of gesture towards long-gone industries was very popular at the time – think of the Dutch firm Mecanoo’s Library of Birmingham, whose decorative hoops were said to have been inspired by the city’s Jewellery Quarter, even though the designers had used them elsewhere. The lace pattern here is much more subtle, rewarding attention: a complex weave scanned and etched into precast concrete panels which is best seen up close, like the terracotta ornament on one of Louis Sullivan’s Chicago School office blocks. Nottingham Contemporary is also the closest the firm has ever come towards the computer-aided design deployed by their more successful contemporaries; not through the ultra-complex parametric equations and ‘scripting’ favoured by Hadid’s partner Patrik Schumacher, but through Photoshop: the duo discovered that darkening a banal digital image of lace would help its successful imprinting (via a latex mould) into the concrete.

Caruso St John, Nottingham Contemporary, facade detail, precast concrete, from Collected Works. Courtesy of Caruso St John and MACK.

Around the time of the building’s completion, Caruso pondered that ‘getting close to vulgarity is an interesting place to go’, drawing on the ‘long tradition of ugliness’ in British architecture – the ‘rogues’ of High Victorian Gothic, the New Brutalism of Stirling and the Smithsons – and not coincidentally offending the good taste of High-Tech. The second volume of Collected Works begins with the V&A Museum of Childhood, an expansion project of the old ‘Brompton Boilers’, a Victorian hangar with instructional mosaics inside, which the firm supplemented with a new set of ornamental patterns in a new entrance pavilion. It was and is highly popular among High-Tech designers to add an abstract, wide-span steel and glass atrium to these sorts of Victorian futurist structures, but for the duo, ‘when we work . . . on a listed Victorian building, we’re interested in explicitly (using) ornament’. They took a similarly sympathetic approach to listed modernist buildings – their small additions to the Barbican (a new ceiling for the auditorium) or Denys Lasdun’s Hallfield Estate (new buildings for the estate’s school) worked with rather than against the ethos of these heroic modernist projects – but from here, the firm’s work develops ever closer to neoclassicism.

This can be seen in the small cafe Caruso St John designed for Chiswick House, the closest they get to Chipperfield, an example of austere, stripped classicism in lush materials (the duo note here that their interest in Burlington’s Palladianism is owed in part to its being ‘a rare example of England leading an architectural movement’). This highly establishment commission, expensively executed, must have helped them secure the job of refurbishing and redesigning Tate Britain. There are small additions throughout the building, but the focus here was a new staircase leading from the building’s Victorian baroque rotunda to the basement cafe, via a sensuous and somewhat camp stone spiral, with incised ornament in its terrazzo surfaces – an idea the firm first tried out in a new chancel for the Cathedral of St Gallen in Switzerland. In the face of the postmodernist and neomodernist additions by James Stirling and John Miller, this re-classicises the building, emphasising the bombast of rotunda and then undercutting it by burrowing underneath. It is also the first of a series of great staircases that the firm would start to specialise in, paradox-filled ascents and descents owing equal debts to Inigo Jones and Berthold Lubetkin.

There is another of these flamboyant staircases in the duo’s most complete London building, the Newport Street Gallery in Vauxhall, which was designed to house the extensive art collection of Damien Hirst – sadly, much less eccentric and interesting than the Walsall art collections of Kathleen Garman and Sally Ryan – and as a new home for his silly and very 1990s pharmaceutical-themed bistro, Pharmacy. It is constructed on top of Hirst’s old studio, a block originally built for West End scenery painting. It has much of the found-object industrial deadpan of the firm’s 1990s work, linking it with the increasingly opulent turn of their designs of the 2010s, and it sits in one of those inner London spaces described so longingly thirty years ago – next to an LCC housing estate, with a scrubby park and some fragmentary Victorian terraces nearby, all hard up against the noisy railway viaduct into Waterloo. But the feeling of freedom that such spaces once offered is gone, with the site loomed over by the cluster of new luxury residential towers on the other side of the viaduct in Nine Elms. These have morphed in shape over the years from cheap, naff versions of High-Tech, like Broadway Malyan’s hideous St George Wharf, into austere brick and stone-clad grids, their quasi-classicism in no way hiding the feverish speculation that has brought them into being. Caruso and St John’s adversaries of the 1990s still build, and have a few successors, such as the bumptious ex-OMA Danish designer Bjarke Ingels or the ridiculous English charlatan Thomas Heatherwick, but they are loathed by critics and younger designers. The architecture schools, and the most feted architects in London, tend now to favour a dialogue with the past, a willingness to use ornament, and a scepticism towards big, dumb, iconic architecture. Caruso St John are now elder statesmen among them. How does this affect their work, and their posture of refusal?

Some of Caruso St John’s early ideas are now clichés: as Tom Wilkinson has pointed out, the found-object approach of leaving as much as possible of an existing building intact, no matter how banal, has become bathetic, as the marks left by an ordinary accidental fire in an ordinary London public building like Battersea Arts Centre are conserved with the same reverence as the scars left by the Battle of Berlin; and fetishizing the mess of a London that is unplanned and unaffordable, rather than unplanned and cheap, is somewhat less appealing. Meanwhile, the old men and women trained by the AA in the sixties and seventies are now so ridiculed by young architects and critics – look, for instance, at the disdain of the meme page Dank Lloyd Wright, or the scorn directed at that generation by the excellent New York Review of Architecture – that one has to remember that they spent the 1980s largely unemployed, submerged under the moronic, anti-urban and ostentatiously reactionary postmodern classicism that dominated that decade. Twenty years ago, it was novel and daring to link neoliberalism to Stalinism as yet another failed utopia, and to argue that the Junkspace elation of Koolhaas in Atlanta or Shenzhen – ‘his thrill at flying ever closer to the naked flame of capital’, as Caruso put it in 2012 – was yet another iteration of Le Corbusier’s wonder at aeroplanes and Ford factories. It is perhaps close now to being common sense.

In an essay on ‘The Alchemy of the Everyday’, Caruso lays out the firm’s case against heroic modernisms, whether of the 1920s or the 2000s: ‘this utopia, any utopia, is simply not interested in or able to engage with the granular detail of reality. Despite modernism’s self-evident interest in the quotidian, with its emphasis on housing, hygiene and the design of kitchens, these all too often lead to simplification rather than the complexity that one would expect from an interest in the everyday’. It is the valuing of everything that distinguishes their work – there are no failures, no eyesores, for Caruso St John, and in a situation where successive forms of working-class housing are seen as ‘problems’ to be solved rather than places to live, this remains refreshing. A planning department inspired by their work would never build an Aylesbury Estate or a Thamesmead, but it would never demolish one, either. Their position is far from a banal anti-modernism – the texts in the second volume of Collected Works refer approvingly to Fischli & Weiss’s photographs of the in-between spaces of Swiss post-war housing, for instance. What it is, is decisively anti-utopian, with the market seen as just another abstract utopia. In aesthetic terms, theirs remains a bracing approach given the tedious style wars between reified versions of modernism and classicism that still rage on social networks, despite their near-total irrelevance to much current practice. In 2012, Caruso lays out an alternative canon: ‘I want to reclaim the English Arts and Crafts, the Chicago School, the Wagnerschule, the Paris of Perret and Pouillon, the Milan School, and other so-called “peripheral” figures for a modernism of realism, a modernism of continuity, and a modernism that has the capacity to be socially and physically engaged’. This is sensible and liberating, but it does not translate well on the internet.

British architecture today is in a strange position. Major new construction outside of London and Manchester has been squeezed into near-nonexistence by austerity. Although Caruso St John’s rejection of ‘iconic architecture’ is now mainstream, they themselves appear to have benefited little from this; any third volume of the Collected Works, dealing with their production since 2012, would so far include just two British buildings – a tiny adaptive re-use project in Arbroath and an office block near King’s Cross. By now, they are effectively a European firm, designing housing, offices and entire city blocks in Germany, Belgium and especially Switzerland, a country which has become a mecca for younger architects, where they can admire the austere, beautifully detailed, somewhat brutalist, somewhat classicist works of cult figures such as Peter Märkli or Valerio Olgiati, and enjoy a global financial centre which still manages to employ its architects to build large quantities of social and co-operative housing. Caruso St John’s influence is very clear on the better London architects today, such as Amin Taha, 6A Architects, Apparata, Studio Weave, et al.: all equally happy referring to Palladio, William Morris, Gropius, Mies and the Smithsons. There is an entire microindustry of this now, with its own favoured photographers such as David Grandorge and Hélène Binet, and its own places of pilgrimage like Ghent or Basel, where Good Architects build Good Architecture at a reasonable scale.

Architecture critics love all of this, finding it a tonic after having to go and watch cladding panels fall off the latest computer-designed Googleplex, tech billionaire’s retreat, or arts centre with nothing in it, usually designed by Ingels, Thom Mayne, Heatherwick or the posthumous firm of Hadid. But relatively few of the alternatives have actually been built, with the position of refusal and the consequences of austerity melding to the point where interesting architecture can largely be found only in tiny infill projects in London suburbia while dross is stacked to the skies in Battersea and Deansgate. As one broadsheet architecture critic privately observed recently, much of his job now consists of reviewing house extensions.

Caruso St John’s deliberate, principled sitting out of the great constructional dramas that British-based architects have participated in – the urbanisation of China, in particular – has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The refusal of utopianism cuts both ways. In the work of Foster, Rogers, Koolhaas or Hadid, the progressivist, teleological, technocratic bent of utopian interwar modernism – however curdled by irony in Koolhaas’s case – was yoked to the building of a radically unequal world. In turn, this has created immense problems, of the sort that utopian modernism emerged to solve in the first place a century ago. A housing crisis the like of which hasn’t been seen in the rich world for a century; a desperate need for green infrastructure to achieve a transition away from fossil fuels; a new wave of public transport to drag people out of their cars. The redress of these enormous problems will surely require utopians as much as realists. But then who needs utopia when you have Switzerland?

Read on: Owen Hatherley, ‘The Government of London’, NLR 122.