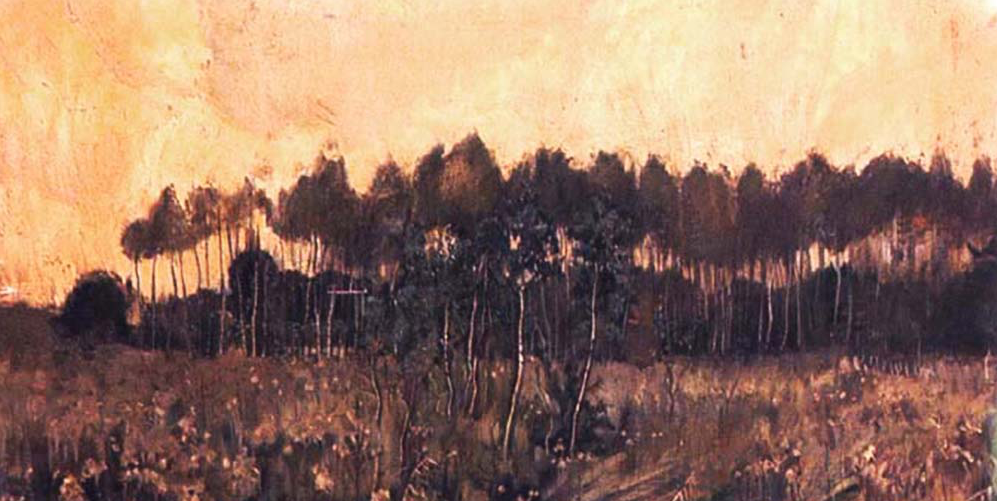

On a recent walk in Białowieża Forest, the immense primeval woodland that straddles Poland and Belarus, I saw a perfectly still figure holding binoculars. It initially appeared to be a birdwatcher, until I drew closer and realized it was a soldier from the Polish army.

In Białowieża, bison stride through oak, ash and linden trees that are hundreds of years old. Recently they’ve been joined by refugees, who are entering the woodland from Belarus. In August, people from countries including Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria were caught crossing into Poland through the forest. For over a month, a group of Afghans has been stranded on the border near the village of Usnarz Górny (north of Białowieża, in the Podlasie region). The ruling Law and Justice government has refused to let them apply for asylum or provide humanitarian aid. ‘We are defending sacred Polish territory’, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said.

European officials and Belarusian exiles have accused Alyaksandr Lukashenka of taking revenge against sanctions by luring migrants to Minsk and releasing them into the EU through Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. In response, Poland has sent 1,800 soldiers to the border, installed barbed-wire coils, and announced the construction of a new 2.5-meter-high fence. Lithuania also announced that it is building a wall on the 679-km border it shares with Belarus.

The EU’s Eastern borderland, and especially the forest, is a long-time site of debate over the difference between ‘ours’ and ‘other’, East and West. Historian Larry Wolf traces this imagined boundary between civilization and backwardness to the educated travellers of the Enlightenment, who expressed horrified fascination with the supposedly barbaric lands they encountered to the East. While competing camps have claimed Białowieża as their own, its entangled history resists ethnic or ideological separation.

During the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the area that spans modern-day Poland, Belarus and Lithuania was united under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After the last partition of Poland in 1795, the forest was turned into a private hunting ground for the Russian tsars, who decimated its population of bison. When Poland gained independence after World War I, it became a national park.

The region was seized by the Soviet Union in 1939, then the Third Reich in 1941. Nazi leader and hunting enthusiast Hermann Göring planned to create an enormous protection zone in Białowieża and populate the area with German peasants. This required the removal of local villagers, who were deported or shot, alongside the extermination of the region’s Jews. Many of them were executed in the woods alongside Poles and Belarusians accused of collaborating with partisans hiding out in the forest.

The current border through Białowieża was created at Yalta. The Belarusian side (Belavezhskaya pushcha) served as a hunting preserve for Soviet leaders, who bonded with Eastern bloc Communists on boozy shooting trips. These displays of affection ceased in 1991, when the Belavezha Accords formally dissolved the Soviet Union at a dacha in the woods.

A visitor approaching the forest from the neighbouring village of Białowieża enters on a dirt path. On the left side is the ‘strict reserve’, where mossy logs sink into layered ground cover; to the right is the national forest, which is subject to clearing and management. The road is so close to the border that cell phones connect to Belarusian telecom networks. A biologist at the Polish Academy of Sciences has warned that the new fence will inhibit the migration of endangered Eurasian lynx, which circulate across the two sides.

On August 29, a group of nine people (four from Egypt, three from Afghanistan, one from Lebanon, and one from Syria) entered Poland through the strict preserve. One of them was a man named Omar, whose relatives told his story to a journalist for Oko Press. Like many of those who have recently tried to cross the border, Omar purchased a travel package to Minsk with the promise that he would be taken to the EU. After reaching the Polish side, he was told by the border guard that he could apply for asylum, only to be dumped back in the woods and ordered to return. His family hasn’t heard from him since.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, James Mark has argued, Eastern European elites eager to prove their membership in Western Europe framed the region as an existential buffer against the East. As Poland joined NATO and the EU, Białowieża became a setting for orientalist fears and fantasies about the threat of the Communist past and the Eastern other (personified by Belarus, which has retained a command economy and close ties to Russia). According to anthropologist Eunice Blavascunas’s recent book on Białowieża, a now-defunct adventure train ride through the woods gave visitors the thrill of being captured by uniformed ‘Soviets’, who forced them to join the Communist Party.

Lukashenka’s migration games have combined with news of asylum-seekers fleeing Afghanistan to fuel anxieties over a possible repeat of the 2015-16 refugee crisis. At the time, populist parties in Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic presented their refusal to accept Syrian refugees sent by the EU as a defence against arrogant liberalism. According to this narrative, only the long-suffering nations of Central Europe were prepared to protect Christian civilization from the dual threat of ‘cultural Communism’ to the East and Islam to the South (which Viktor Orbán sought to keep out by building a steel fence on Hungary’s border with Serbia). Since 2016, as the bloc has fortified its external borders and paid large sums to Turkey and other countries to ward off migrants, this stance has coalesced with the official view from Brussels. The latter is currently preparing a massive financial package to Afghanistan’s neighbours in an attempt to keep displaced people from coming to Europe.

Poland flaunts its growing role as a safe haven for political refugees from Belarus. These include the sprinter Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, who is seeking asylum after she criticized her coaches on social media during the Tokyo Olympics and Belarusian officials tried to force her onto a flight home. After arriving in Warsaw, Tsimanouskaya appeared on an evening news program whose host excitedly asked her what she wanted to see in her new country. While welcoming Slavs who flatter its self-image, Law and Justice rejects arrivals from Africa and the Middle East, with a revival of the xenophobic rhetoric it rode to power. ‘Poland will defend itself against a wave of refugees, just as it did in 2015 ’, Minister of Culture Piotr Gliński said.

Some inhabitants of border villages offer food to people who turn up in cornfields and cow sheds, while others place an immediate call to the border guard. In reportage for Krytyka Polityczna, sociologists Sylwia Urbańska and Przemysław Sadura found that fear of the newcomers tends to be greatest among women who have returned from years working as cleaners in Western Europe, where they competed with people from majority-Muslim countries for the lowest-paid jobs.

Criticism of the government’s policy often invokes national memory of the Holocaust. Social media users retweeted a speech by Auschwitz survivor Marian Turski that called for an Eleventh Commandment: ‘thou shalt not be indifferent.’ Several opposition MPs and two priests attempted to bring food, medicine and supplies to the people at Usnarz Górny, where they were rebuffed by border guards. Donald Tusk, the leader of the party Civic Platform, has taken a more cautious approach, saying that the government should provide assistance to stranded refugees while emphasizing that ‘the Polish border must be kept intact.’

For Poles across the political spectrum, joint Russian-Belarusian military exercises near the border this month lend credence to the narrative that the region is in danger of Eastern invasion. Russia’s defence ministry has announced that a record 200,000 troops are taking part in the Zapad-2021 demonstration. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, playing his part in the neo-Cold War script, vowed that the organization would be ‘vigilant.’

By offering protection against outsiders, Law and Justice have cast themselves as the perverse heirs of previous rulers who tried to ‘purify’ a region known for human and ecological diversity. Their efforts enjoy the backing of EU border agency Frontex, which recently sponsored repatriation flights for citizens of Iraq. In early September, the Polish government (following Lithuania and Latvia) declared a state of emergency that requires activists and journalists to stay at least five kilometres away from the border zone. Aid workers previously communicated with the Afghans near Usnarz Górny through a megaphone; now, the latter are left without assistance and beyond the gaze of cameras. Some of those who arrived with Omar told a lawyer that they had already been pushed back into the forest several times. If it happens again, they said, they might not make it out alive.

Read on: Alexandra Reza, ‘Imagined Transmigrations’, NLR 115.