The biographical outline that typically opens an essay on Paula Rego begins with her birth to Lisbon-based Anglophiles in 1935. It registers her first encounter with England in the early 1950s when her parents – despairing at the Estado Novo regime – sent her to a finishing school in Kent. Via the Slade, the young Rego developed through contact with the London Group, coming to serve as the feminist cherry on their cake. Dividing her time between the two countries for several years, she eventually settled in London with the English painter Victor Willing. From there, her story arcs towards recognition by the British establishment, culminating in honours (she was made a Dame of the Empire in 2010) and retrospectives (the latest runs at Tate Britain until 24 October).

Fame of this kind has led Rego’s career to be plotted as a kind of social narrative, its twists and turns bent to fit agreeable cultural metaphors. Her early work – drab oil paintings like Interrogation (1950), in which a woman flanked by the bulging trousers of two male torturers collapses on herself like a broken Anglepoise lamp, and Portrait of José Figueiroa Rego (1954–55), where the face of Rego’s father wilts into his own fist – are said to articulate a raw breed of anguish connected with her birthplace. Paintings such as Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960), which depicts the dictator, his red and white belly stuffed with chauvinist dogmas, disgorging a curl of bile into the canvas’s bottom-left corner, soon garnered Rego a reputation as a fearless critic of the dictatorship. Yet as she becomes established in London a bifurcation occurs: the biographical image of Rego qua British national treasure comes to exist almost independently of her art. She is ‘one of our own’, yet the critical implications of her work are conceived as applying exclusively to the country of her birth.

Tate Britain’s exhibition is a case in point. Foregrounding Rego’s examination of the female experience, it confines the political and cultural critique her work offers, or else reduces its import to individual psychology. This is primarily achieved by unmooring her paintings from their historical context. By the time of Wife Cuts off Red Monkey’s Tail (1981), Salazar has been replaced with the titular animal: a thin pale, orange monkey who vomits while his wife stands behind him wielding a pair of scissors. Biographical readings of this work and others in which the monkey recurs (Red Monkey Beats His Wife; Red Monkey Offers Bear a Poisoned Dove) refer to Willing’s marital betrayals and Rego’s fantasies of revenge: domestic dramas that occlude any wider political landscape. The same interpretation is affixed to the renowned pictures of stocky girls looming over pets or performing household chores, which are framed in terms of Willing’s late illness. These complex portraits of female aggression – in which women are variously rendered as lovers, carers and murderers – are presented as less concerned with matrices of political power than with psychosexual impulses. The bulging fossilised skirt of the bullish girl in Snare (1987) may hint at the darkness of the Portuguese metropole, but it has nothing to do with Thatcher’s Britain.

Instead, we are told that such paintings are primarily about personal revelations Rego had while undergoing Jungian analysis. As Jung himself observed, there are hazards involved in inferring an artwork’s social meaning from the intimate life of its creator. The curators direct us to find in Rego’s art ‘the repressed desires, weaknesses and sexual instincts within the unconscious mind’, but Jung distrusted any such approach. ‘The golden gleam of artistic creation’, he wrote in 1923, ‘is extinguished as soon as we apply to it the same corrosive method which we use in analysing the fantasies of hysteria’. Rather than hunting for visual symptoms of the artist’s subterranean desires, he proposed that we view art as a reflection of a collective unconscious which, contra Freud, was never ‘repressed’ or forgotten. Nor was it pre-political. For Jung, the archetypes revealed by artistic creation were social constructions – manifestations of collective thought, or the ‘psychic residua of innumerable experiences of the same type’.

The exhibition presents the paintings completed during Rego’s ‘annus mirabilis’ of 1987 as referencing specific Portuguese people and places, but they can be better understood as archetypal constructs: The Soldier’s Daughter; The Policeman’s Daughter; The Cadet and his Sister. In these renowned de Chirico-esque stonescapes we find menacing military WAGs, their strong arms engaged in acts of force that belie the softness of their faces. The soldier’s daughter straddles the neck of a large, floppy goose whose plumage she grips with knuckles almost as white as the feathers themselves. The policeman’s daughter plunges her fist into daddy’s long black boot, polishing it with such intensity that her knee seems to grind against the table. These figures may resonate with themes from Salazar’s Portugal, yet they have no literal kinship with the state or its servants. They are neither psychological portraits of individual women nor ‘indictments of Salazar’s dictatorship’ as the Tate’s curators claim, but rather archetypes of feminine desire as produced by the carceral-military imaginary. For Rego, this imaginary operates in both the Estado Novo and the British Empire, though it is reducible to neither.

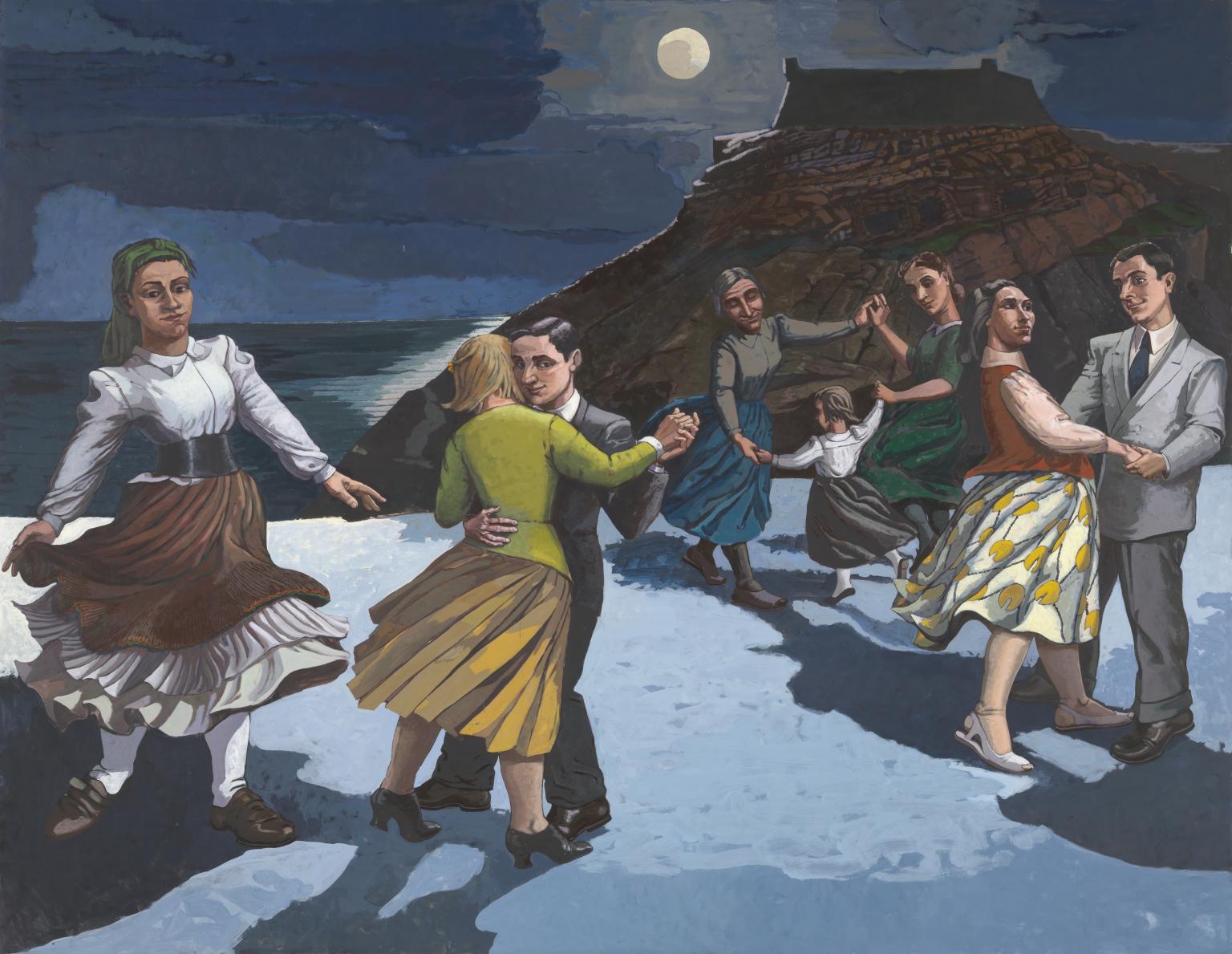

In The Dance (1988), a redoubled husband figure, appearing once with his wife and once with another woman, twirls around a moonlit beach in the shadow of a military fort. The figure of the wife is multiplied such that she appears in five separate stages of her life. Here, the drama of familial loyalty and betrayal is indivisible from the backdrop of war, but the resemblance between the military base in The Dance and the Fort of Milreu on Portugal’s Atlantic coast is incidental. The fort, and the husband, are instead symbols of masculine power without specific referent. It is precisely the generality of these images that gives them equal resonance across Rego’s two national contexts.

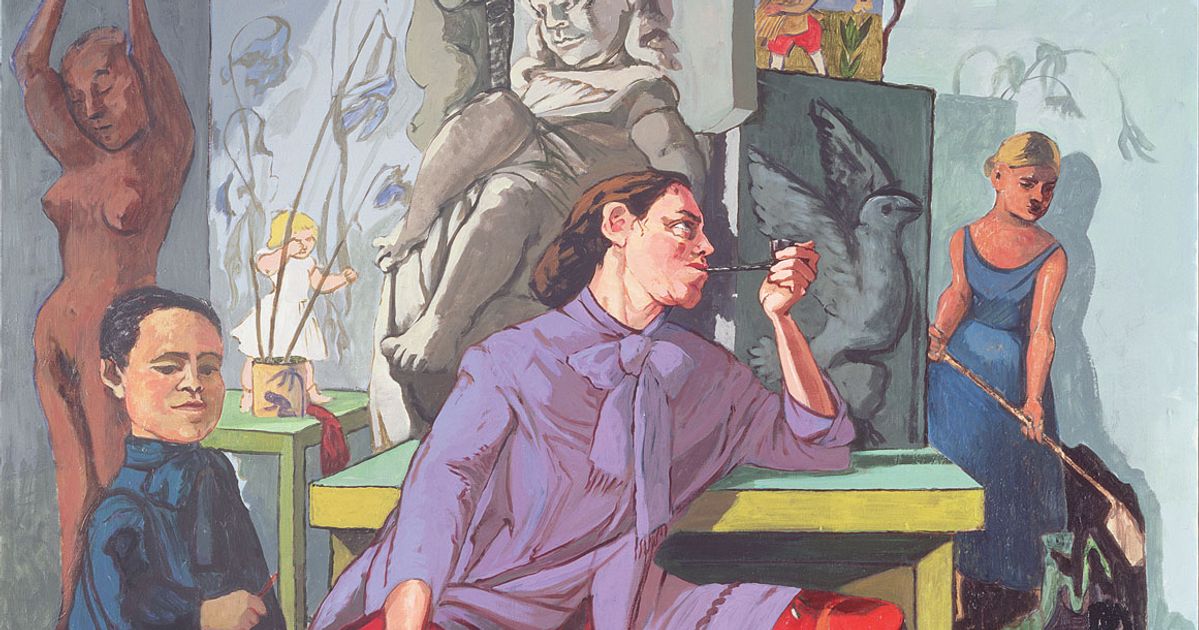

For Jung, the beauty of the archetype lay in its connection to lost forms of greatness. Types unlock ‘ideals’ which are generally linked to forms of reactionary nostalgia: ‘the mother country’, ‘the symbolic value of our native land’, and so on. Jung writes that art’s social function is to conjure up essential virtues that the spirit of the age is lacking. Although Rego’s work is indebted to Jung on various levels, this is precisely the vision that she seeks to overturn. Where Jung sees valour, Rego sees only vomit. Her excavations of the collective unconscious spurn idealism for brutal realism. Many of her paintings are tragic, rather than triumphal, retellings – of folk tales, nursery rhymes, cartoons, novels, plays and poems. Take The Maids (1987), which reimagines the eponymous protagonists of Jean Genet’s play Les Bonnes (1947): a stylised narrative of the real-life Papin sisters, famed in the nineteenth century as servants who murdered their mistress. Genet depicts the sisters as furtive sadomasochists, restaging scenes of their own domination while wearing their employer’s clothes. When Rego represents them forty years later, the ‘mistress’ is the one who appears to have dressed up for the occasion; thick, burly legs extend beneath her skirt, while the faint outline of a moustache can be seen above her upper lip. Meanwhile, the maid whose hand is gently poised against her master’s neck is given dark skin, as though to hint at an act of colonial retribution.

In Rego’s retellings we see not only the psychoanalytic imperative to articulate again (bring into the present, revisibilise), but also a political will to articulate anew (disrupt, subvert, rearrange) – as in Time, Past and Present (1990), based on Antonello’s St Jerome in His Study (c.1475). The saint is reconceived as a pensive man amid several children. One of them attempts to draw him, yet her page remains blank; another, in the doorway behind him, seems to fade into sand. Antonello’s backdrop of verdant fields is replaced by the empty yellow of an infinite, sea-less beach. Hanging on the wall in the right foreground is a painted angel whose scorched tones evoke Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920): the painting that for Walter Benjamin captures the force we mistakenly refer to as ‘progress’. Rather than longing for the past, as in Jung, Rego uses it to estrange the present, in a procedure more closely allied with Benjamin’s image of messianic time. Her paintings make legible a reordered continuity between the disfigurement of the now and the mistakes of the what-has-been.

Absent from Rego’s art however are the utopias that Benjamin hoped this process would bring forth. In their place we have an unflinching treatment of desire which emphasises its ability to trap and ensnare its subjects. The policeman’s daughter gets off on servitude to the boot; the maids are enthralled by the murderous pleasures derived from their own humiliation. If Rego gives us surprising reconfigurations of the past, she makes no special effort to imagine the route beyond it. In this regard, the final room of Tate’s exhibition is perhaps the most starkly ill-conceived:

Rego is an artist who has consistently made work that responds to and fights injustice. In keeping with this lifelong concern, we end this retrospective exhibition with this group of powerful, harrowing works of art that serve as a provocation for action. Rego’s and our wish is that there might be an Escape, and more justice for all women.

If a woman finds her desire trained on her own, or other women’s subjection, how can this desire be retranslated into an impulse to ‘escape’? The evasive abstraction of the curatorial note – ‘works of art that serve as a provocation for action’ – is sufficient indication that Rego offers no clear answer. Yet, perhaps, by turning this desire into such visceral forms of disgust, she plants some seed of its eventual redirection.

Read on: Herbert Marcuse, ‘Art as Form of Reality’, NLR I/74.