With Biden in the White House, do you foresee any major US policy changes towards West Asia?

Let us look at what we are changing from before we look at what we are changing to. This is difficult to do because Trump’s policies, assuming them to be coherent strategies, were chaotic in both conception and implementation. Trump did not start any new wars in West Asia, though he did green-light the Turkish invasion of northern Syria in 2019. He withdrew from the nuclear deal with Iran in 2018, but relied on economic sanctions, not military action, to exert pressure on Iran. In the three countries where America was already engaged in military action – Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria – surprisingly little has changed. Keep in mind that his foreign policy was heavily diluted by the more interventionist policies of the Pentagon and the US foreign-policy establishment in Washington. They successfully blocked or slowed down Trump’s attempted withdrawals from what he termed the ‘endless wars’ in West Asia. It is not clear, however, that they have a realistic alternative approach.

Biden will be subject to the same institutional pressures as Trump was and is unlikely to resist them. He may be less sympathetic to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Saudi Arabia and Netanyahu in Israel, but I doubt if the relationship between the US and either country will change very much. The next Secretary of State, Tony Blinken, approved the Iraq invasion of 2003, the regime change in Libya in 2011, and wanted a more aggressive policy in Syria under Obama. It does not sound as if he has learned much from the failure of past US actions in West Asia. This is not just a matter of personalities: the US establishment is genuinely divided about the merits and demerits of foreign intervention. It is also constrained by the fact that there is no public appetite in America for more foreign wars. For all his rhetorical bombast, Trump was careful not to get Americans killed in West Asia, and it would be damaging for Biden and the Democrats if they fail to do the same.

Will the Biden administration want to resuscitate the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran?

Biden says he wants to resume negotiations, but there will be difficulties. One, security establishments in the West are against it. Two, Saudi Arabia and its allies are against it, and so, more significantly, is Israel. Three, the Iranians did not get the relief from sanctions they expected from the nuclear deal of 2015, so they have less incentive to re-engage.

A misunderstanding – perhaps an intentional one – on the side of Western states, Israelis and Saudis/Emiratis about the nature of the deal may prevent its resurrection. They claim that Iran used it as cover for political interference elsewhere in the region. But Iranian action, and its ability to project its influence abroad, is high in countries where there are powerful Shia communities such as Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, Afghanistan – and low elsewhere. Iran is never going to stop its intervention in these countries in which, in any case, the Iranians are on the winning side.

Gulf countries such as the UAE and Bahrain have recently established diplomatic relations with Israel. What effect will this have on Israel-Palestine relations?

This weakens the Palestinians, though they were very weak already. The UAE and Bahrain (the latter is significant only as a proxy of Saudi Arabia) did not do much for the Palestinians in any case. Yet, however weak the Palestinians become, they are not going to evaporate so, as before, Israel holds all the high cards but cannot win the game.

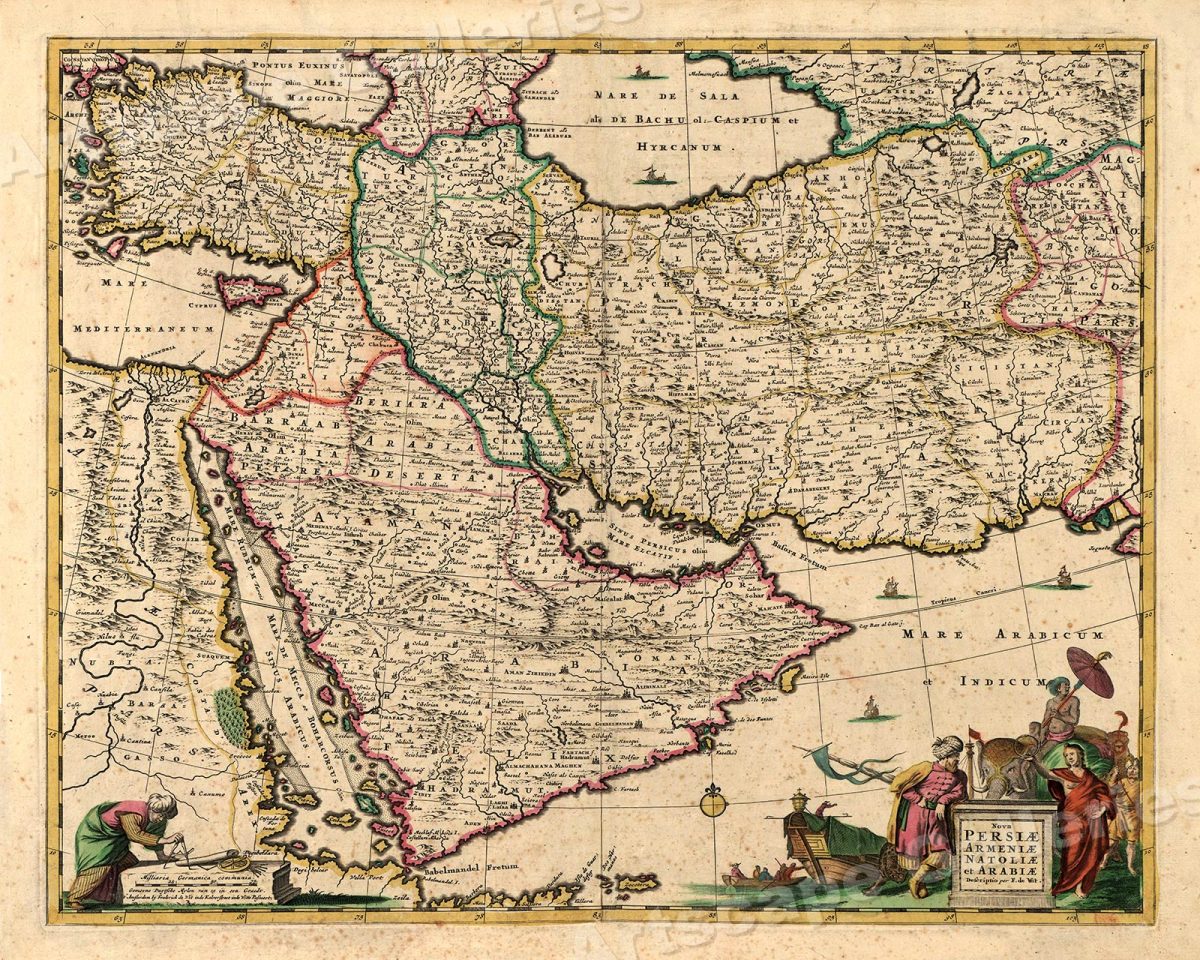

You’ve said that ‘great powers fight out their differences in West Asia’. Why is that?

West Asia has been unstable since the end of the Ottoman Empire. It has been an arena for international confrontation ever since. Reasons for this include, one, oil; two, Israel; three, states in West Asia look weak but societies are strong and very difficult to conquer – witness Israel’s disastrous invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and the even more self-destructive US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Invaders and occupiers in West Asia have great difficulty turning military superiority into political dominance.

What role did colonial rule play in the ethno-political conflicts of West Asia?

Foreign intervention usually exploits and exacerbates sectarian and ethnic divisions, though it seldom entirely creates them. Britain relied on the urban Sunnis to rule Iraq; the French looked to minorities such as Christians in Lebanon to rule there. More recently, foreign powers gave money, arms and political support to factions in Iraq to enhance their own influence but fuelling civil war. Opponents of Saddam Hussein genuinely believed that he had created religious divisions and these would disappear when he was overthrown. But, on the contrary, they got much deeper and more lethal. The same is true of Syria: the battle lines generally ran along sectarian and ethnic boundaries. Intervention in West Asia has traditionally ended badly for British and American leaders: three British Prime Ministers (David Lloyd George, Anthony Eden and Tony Blair) lost power or were badly damaged by the West Asian interventions they launched, as were three American presidents (Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush).

You’ve said that the Iran–Iraq war was ‘the opening chapter’ of a series of conflicts in the region that have shaped the politics of the modern world. Why?

The Iran Revolution was a turning point, out of which came the Iran-Iraq war that in turn exacerbated Shia-Sunni hostility throughout the region. Saddam Hussein won a technical victory in the war but then overplayed his hand by invading Kuwait. Aside from Iraq, the sides confronting one another in West Asia are much the same now as they were 40 years ago. One big change is the recent emergence of Turkey as an important player, intervening militarily in Syria, Iraq, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh.

What role do proxy groups play in West Asia?

One has to be careful to distinguish between different ‘proxy groups’. The phrase is often used as a form of abuse to denigrate movements with strong indigenous support as mere pawns – and sometimes this is true. The Houthis in Yemen, for instance, have been fighting for years and receive little material help from Iran, but are almost always described in the Western media as ‘Iranian-backed Houthis’, implying that they are simply Iranian proxies, which they are not. In Iraq, some of the Hashd al-Shaabi (Shia paramilitaries) are under orders from Iran, but others are independent. The Kurds in Syria rely on the US militarily and politically because they fear Turkey, but they are certainly not American puppets.

What has been the outcome of ‘the War on Terror’?

It was America’s post-9/11 wars, supposedly against ‘terrorists’, that created or increased chaos in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria. These wars turned out to be endless, so populations had no choice but to flee. In Europe, the refugee exodus from Syria peaked in 2015–16 and was probably a decisive factor in the vote for Brexit in the UK referendum. All the anti-immigrant parties in Europe were boosted. The intervention by Britain and France in Libya (backed by the US) in 2011 destroyed the Libyan state and opened the door to a flood of refugees from further south seeking to cross the Mediterranean. The Europeans in particular remain in a state of denial about the role of their own foreign policy in sparking these population movements.

You were one of the first to warn about the emergence of ISIS. What led to its rise?

ISIS was born out of the chaos in the region. Before 9/11, Al Qaeda was a small organisation. Al Qaeda in Iraq, created by the US invasion, was far more powerful. Defeated by 2009, it was able to resurrect itself as ISIS after the start of the civil war in Syria. I am surprised now that more people did not understand how strong ISIS had become by 2014, the year they captured Mosul in northern Iraq. They had already taken Fallujah, 40 miles west of Baghdad earlier in the year, and the Iraqi Army had failed to get them out. This should have been a sign that ISIS was stronger and the Iraqi government weaker than had been imagined. ISIS was a monstrous organisation, but militarily it was very effective in using a mixture of snipers, suicide bombers, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and booby traps. Its weakness militarily was that it had no answer to air power.

Do you expect to see ISIS’s resurgence?

There is a resurgence of ISIS in Iraq and Syria, not on the scale of 2012–14, but still significant. I am not convinced that clones of ISIS in other countries are as significant as is sometimes made out to be. ISIS lost its last territory with the fall of the Baghouz pocket in eastern Syria in March 2019. ISIS leader and caliph, Abu Baqr al-Baghdadi, killed himself during a raid by American Special Forces on a house in northwest Syria in October the same year. Since then events have favoured ISIS: the US-led coalition against it has fragmented and the defeat of ISIS no longer has the priority it once had; Sunni Arabs, the community from which ISIS springs in Iraq and Syria, remain impoverished and disaffected; ISIS has plenty of experience in guerilla war, to which it has reverted, because holding fixed positions led to it suffering heavy losses from artillery and airstrikes. The Syrian and Iraqi governments, as well as the Kurds, all have weaknesses like corruption that ISIS can exploit.

That said ISIS no longer has the advantage of surprise, the momentum that comes from victories, or the tolerance – and probably the covert support – of foreign countries (notably Turkey) that it had in 2014–16. The Sunni Arabs suffered hideously because of the last ISIS offensive with the part destruction of Mosul and Raqqa, their two biggest cities. Many will not want to repeat the experience. Local security forces are more effective than they were five years ago.

Was ISIS an anti-imperial force? Not primarily, since their main enemies were Shia and other non-Sunni minorities. Objectively, ISIS energised and legitimised foreign intervention wherever it had strength.

You’ve recently argued that ‘oil states are declining’. If so, what are the implications for the region and international politics at large?

Biden or no Biden, the nature of power in West Asia is changing. Oil states are no longer what they were because the price of oil is down and is likely to stay that way. This is profoundly destabilising: between 2012 and 2020, the oil revenue of Arab oil producers fell by two-thirds, from $1 trillion to $300 billion, in a single year. In other words, the ability of the rulers of a state like Saudi Arabia to project power abroad and retain power at home has significantly diminished. A country like Iraq has just half the income it needs from oil – and it has no other exports – to pay state employees and to prevent the bankruptcy of the Iraqi state. People forget what a peculiar situation we have had in West Asia over the last half century, with countries that would have had marginal or limited importance in the world – like Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Libya and Iran – becoming international political players thanks to their oil wealth. They could afford to buy off domestic dissent by creating vast patronage machines that provided well-paid jobs. But there is no longer the money to do this. The end of the oil-state era is not yet entirely with us, but it is approaching fast.

Is the US now trying to extricate itself from the region?

Obama and Trump both said they wanted to reduce on-the-ground commitments in West Asia, but somehow the US is still there. In reality, the Americans would like to enjoy the advantages of imperial control or influence but without the perils it involves. They would prefer to operate by employing other means such as economic sanctions or local proxies. The Obama foreign policy was meant to see ‘a switch to Asia’ but this never really happened, and it was the West Asian crises that continued to dominate the agenda in the White House. In other words, the US would like to withdraw from West Asia, but only on its own terms.

Across West Asia, left movements have increasingly been replaced by Islamist forces. How would you explain this change?

I am not sure that this is quite as true as it used to be because Islamist rule in its different varieties has turned out to be as corrupt and violent as secular rule. Both have been discredited by their years in power. Secularism was always strongest among the elite in countries like Iraq, Turkey, Egypt. It never offered much to the poor. To a substantial degree the same thing that happened to the Left is now happening to Islamist forces. Elites with a supposedly socialist ideology were as kleptocratic as everybody else. The same was often true of nationalism because religious identity often remained stronger than national identity.

How would you analyse the changing inter-state dynamics in West Asia?

States have gone up and down. The crucial change in the relative strength of states was the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, so regional powers that it had protected became vulnerable to regime change. Russia’s military intervention in Syria since 2015 has somewhat reversed this – but not entirely. Iran became much more of a regional power thanks to the elimination of its two hostile neighbours – the Taliban in Afghanistan and Saddam Hussein in Iraq – by the US post-9/11. It is under strong pressure from US sanctions, but these were never likely to bring about its effective surrender. Iraq and Syria are too divided for state power to be rebuilt. Saudi Arabia’s more aggressive foreign policy under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman produced few successes, aside from cultivating Trump and his entourage. Does the embrace of Israel by some of the Gulf rulers enhance their power or that of Israel? Probably less than they hope. Likewise, the Palestinians are weakened, but the ‘Palestinian Question’ has not gone away, will not do so, and will always return.

What of the ongoing civil wars and ethnic conflicts in Syria and Iraq?

The main sectarian and ethnic communities – Sunni, Shia, Kurd – will still be there in both countries, though there are winners and losers. The Sunni Arabs lost power in Iraq in 2003 and the Shia Arabs and Kurds have been dominant ever since. The Sunnis have failed to reverse this despite two rebellions, roughly 2003–07 and 2013–17 during which they suffered severe losses. The Kurds expanded their power (taking Kirkuk), but could not cling on to their gains. Nevertheless, they remain a powerful player.

In Syria, the Alawites (a variant of Shi’ism) hold power now as they did in 2011 at the start of the Arab Spring. The majority Sunni Arabs, under jihadi leadership, have suffered a catastrophic defeat with more than five million of them refugees. The Kurds expanded their power thanks to their military alliance with the US, but they are under serious threat from Turkey that has invaded two Kurdish enclaves and expelled the inhabitants.

The Kurds’ problem is that they are a powerful minority in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, but all these states oppose them becoming an independent nation state. They did achieve quasi-independence in Iraq and Syria thanks to central governments in Damascus and Baghdad being weakened by ISIS and thanks to American backing. Without these two factors the Kurdish communities will be squeezed. They will remain a power in Iraq, but in Syria their position is more fragile.

How do you look back at your four decades of reporting from the region?

I am still amazed by the regularity with which Western powers, notably the US, launch military and political ventures in West Asia without knowing the real risks. They do not seem to learn from their grim experience. Reporting this was always dangerous and is getting more so.

A longer version of this interview appears in the Indian fortnightly Frontline on 15 January 2021. The questions – some of which have been shortened – were asked by Jipson John and Jitheesh P.M.