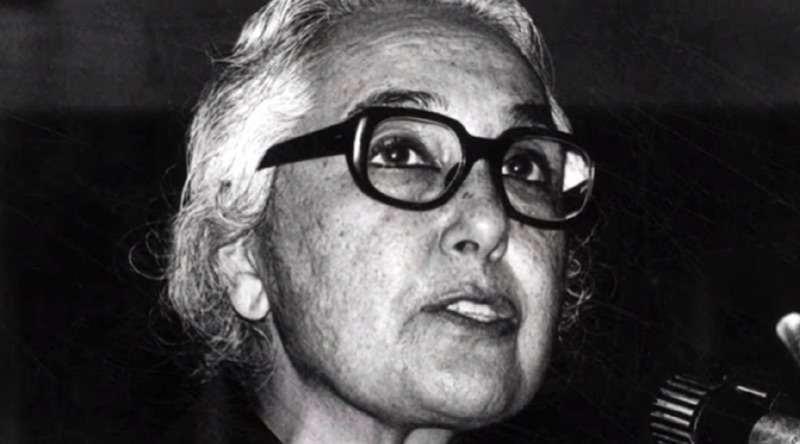

Ranajit Guha, who died recently in the suburbs of Vienna where he spent the last decades of his life, was undoubtedly one of the most influential intellectuals on the Indian left in the twentieth century, whose shadow fell well beyond the confines of the subcontinent. As the founder and guru (or ‘pope’, as some facetiously called him) of the historiographical movement known as Subaltern Studies, his relatively modest body of written work was read and misread in many parts of the world, eventually becoming a part of the canon of postcolonial studies. Guha relished the cut and thrust of intellectual confrontations for much of his academic career, though he became somewhat quietist in the last quarter of his life, when he took a surprising metaphysical turn that attempted to combine his readings of Martin Heidegger and classical Indian philosophy. This confrontational style brought him both fiercely loyal followers and virulent detractors, the latter including many among the mainstream left in India and abroad.

Guha was never one to tread the beaten path, despite the circumstances of relative social privilege into which he was born. His family was one of rentiers in the eastern part of riverine Bengal (today’s Bangladesh), beneficiaries of the Permanent Settlement instituted by Lord Cornwallis in 1793. The area of Bakarganj (or Barisal) from which he hailed was also the birthplace of another Bengali historian, Tapan Raychaudhuri (1926-2014) from a similar zamindar background. Raychaudhuri was himself a complex figure, a raconteur and bon viveur with a melancholy streak, who was destined to play Porthos to Guha’s Aramis. Guha was sent to Kolkata (Calcutta) for his schooling in the 1930s, where he attended the prestigious Presidency College in that city, and soon became active as a Communist. It would have been in these years that he acquired his violent aversion to the ‘comprador’ Gandhi and his version of nationalist politics, which accompanied him for much of his life. He also came under the influence of an important Marxist historian of the time, Sushobhan Sarkar, while at the same time developing a stormy relationship with another leading figure, Narendra Krishna Sinha (not at all a Marxist), under whose supervision he was meant to work on a thesis concerning colonial economic history in Bengal, which was never completed. Around the time of Indian independence, Guha left Kolkata briefly for Mumbai, and in December 1947 travelled to Paris as a representative to the World Federation of Democratic Youth, led for a time by the controversial Aleksandr Shelepin.

Over the next few years, until his return to Kolkata in 1953, Guha travelled widely in Eastern Europe, the western Islamic world, and even China; this included a two-year sojourn in Poland, where he met and married his first wife. On his return to India, he was already accompanied by ‘an aura of heroism’ (as one of his friends wrote) and exercised a degree of charisma and mystique over younger colleagues that would serve him well later. After a brief stint as a union organizer in Kolkata, he embarked on a peripatetic career in undergraduate teaching and began publishing his first essays on the origins of the Permanent Settlement in the mid-1950s. But these years also saw Guha’s estrangement from the Communist establishment, since – as for many of his generation – the Hungarian crisis of 1956 proved a turning point. Though his plans to defend a doctoral thesis never came to fruition, he was eventually able to find a position in 1958 at the newly founded Jadavpur University, under the wing of his former teacher Sarkar. But he quickly abandoned this post to move first to Manchester and then to Sussex University, where he then spent nearly two decades. There is much about this phase of his career around 1960 that remains obscure, including how a barely published historian managed to obtain these positions in the United Kingdom, where few other Indian historians had penetrated. Oral tradition has it that he was also proposed for a position in Paris, at the VIe Section of the École Pratique des Hautes Études, apparently at the initiative of the American economic historian Daniel Thorner (himself a refugee in Paris from McCarthyite persecution). It was also Thorner who helped arrange the publication through Mouton & Co of Guha’s first book, A Rule of Property for Bengal (1963).

This work remains something of a puzzle six decades after its first publication. Though begun as a work of economic history, it eventually became what is quite clearly an exercise in the history of ideas. Driving it at a basic level was Guha’s own childhood experience in a rural context where the Cornwallis Permanent Settlement had set the rules of the game, eventually leading (in some views) to the progressive agrarian decline of Bengal over a century and a half. But rather than analyzing class relations or related questions, Guha instead turned to debates among East India Company administrators in Bengal in the 1770s and 1780s over how the agrarian resources of the province were to be managed. This was presented as a complex struggle between different tendencies in political economy, influenced on the one hand by the Physiocrats in all their variety and splendour, and on the other by adherents of the Scottish Enlightenment (to which Governor-General Warren Hastings was attached). Demonstrating an impressive talent for close reading, Guha took apart the minutes, proposals and counterproposals that were presented and debated in the administrative councils of the time. A central figure who emerged in all this was the Dublin-born Philip Francis. While the opposition between Francis and Hastings had usually been read simply through the prism of factional politics, Guha was able to elevate the differences to a genuine intellectual debate, with lasting consequences for Bengal.

At the same time, it may be said that the work showed little or no concern with the ‘ground realities’ of eighteenth-century Bengal, and even less with the complex property regimes that had been in place before Company rule. This would have required Guha to engage with Mughal history and issues of Hanafite Muslim law, which were rather distant from his inclinations. Furthermore, there is little in A Rule of Property to suggest that it is a Marxist history, however broadly one wishes to interpret this term. Reviewers at the time often compared it with another work that had appeared a few years earlier, Eric Stokes’s The English Utilitarians and India (1959), probably to Guha’s chagrin. Stokes painted with a broader brush and embraced a larger chronology, but also showed less talent for the close reading of texts. But there is probably more that unites these books than separates them. While Stokes’s work was quite widely acclaimed, Guha’s somewhat unfairly languished for a time in obscurity. It is noticeable that for the remainder of the 1960s, Guha more or less ceased to publish, and when he did so in 1969 (in the form of a review of a long-forgotten edited volume on Indian nationalism) it was a bitter attack on the Indian history practiced in England, including Sussex University, ‘where the students are inducted into the rationale of […] thinly disguised imperialist procedure’. It was around this time that Guha decided to spend a sabbatical year in India, based at the Delhi School of Economics through the mediation of his friend Raychaudhuri who was teaching there.

The communist movement in India to which Guha had been attached in the 1940s and early 1950s had by now undergone considerable changes. The pro-Soviet Communist Party of India (CPI) had in 1964 split to produce the CPI(M), which was initially more oriented to Chinese communism and far more hostile to the ruling Indian Congress party. However, in 1967, a further splintering occurred in the context of a rural uprising in north Bengal, to produce the CPI(ML), which eschewed parliamentary politics in favour of a strategy of armed peasant and student mobilization. Radical student groups in cities such as Kolkata and Delhi formed in support of the tendency, generally known in Indian parlance as ‘Naxalites’. Guha, a visitor to Delhi in 1970-71, found this new movement attractive given his own pro-Maoist thinking and began to frequent these student groups. A handful of memoirs have gone over this ground, including a recent one by the development economist Pranab Bardhan. Owing to his fieldwork, Bardhan had a good grasp of Indian rural problems and was less than impressed with what he saw at a rather cloak-and-dagger meeting orchestrated by Guha, describing it in Charaiveti (2021-22) as a ‘collection of clichés’, with speakers ‘regurgitating rhetoric … learned from some cheap pamphlet’. Nevertheless, some of these students not only became activists but also historians, drawing directly on Guha’s formulations for inspiration.

The first of Guha’s renewed historical interventions was an essay, first published in 1972 but with subsequent incarnations, on the Indigo rebellion of 1860 in Bengal. This was accompanied in the following years by several texts of political commentary concerning the Congress and its political profile as well as state repression and democracy in India. Amid the political turbulence of the decade (symbolized by the infamous period of Emergency declared by Indira Gandhi), Guha’s intellectual influence began to spread. In part, this was aided by the move of Raychaudhuri to a position in Oxford; several of Raychaudhuri’s doctoral students came to be advised in reality by Guha, acting as a sort of éminence grise based in Brighton. This eventually led to a series of informal meetings in the UK in 1979-80, where a collective decision was made to launch the movement called ‘Subaltern Studies’, using a term drawn from Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. The first volume with this title appeared to considerable fanfare in 1982 and was followed a year later by Guha’s second book, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India.

This, after roughly two decades of relative occlusion, was the moment of Guha’s second coming. In an opening salvo in the first volume of Subaltern Studies, Guha railed against the ‘long-standing tradition of elitism in South Asian studies’, and after listing various elements which composed the foreign and indigenous elites, summarily declared that the ‘subalterns’ were the ‘demographic difference between the total Indian population and all those we have described as the “elite”’. He further argued that the ‘subalterns’ or ‘people’ had their own ‘autonomous domain’ of political action, and that an elitist view of Indian nationalism had led to a consensual narrative which laid aside ‘the contribution made by the people on their own, that is, independently of the elite to the making and development of this nationalism’. This open attack on not only British historians but Indian ones was the occasion for a set of violent exchanges, particularly with historians attached to the CPI(M), as well as more conventional nationalists. These debates occupied much of the 1980s, by which time Guha had moved to his last academic position at the Australian National University. By the end of the decade, and the publication of six volumes under Guha’s stewardship, Subaltern Studies had established itself as the dominant force in the study of modern Indian history.

This was despite the doubt cast on the originality of the project itself, given earlier forms of history-from-below, as well as issues related to the highly uneven contents of the six volumes. Intellectual fatigue with the standard left-nationalist historiography may explain some of this triumph, but the novel jargon of the new school also played a part. During the 1990s, the main thrust of the project as a contribution to radical social history became progressively diluted, and the group itself began to fragment and disperse, with some bitter recriminations from erstwhile participants. By the time of the twelfth volume, published in 2005, the project had largely lost shape and become mired in a fruitless engagement with deconstructionism on the one hand, and cultural essentialism on the other.

Returning to the original moment of 1982-83, however, several peculiar features of Guha’s stance are worth mentioning. One was his insistent adherence to a particular reading of the structuralism that had been popular in the 1960s, not so much the structural anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss as the reinterpretation of Saussurian linguistics by figures like Roland Barthes. As we know, Barthes’s own position shifted considerably in the years after his ‘Introduction à l’analyse structurale des récits’ (1966), but Guha did not follow him in this trajectory. Instead, he stuck to certain strikingly simple ideas based on a binary division between elites and subalterns. This is turn became the basis of another article of faith, namely that the voice and perspective of the subaltern could alchemically be extracted from colonial records of repression through certain protocols of translation. These ideas, expressed by Guha in some form in the first volumes of Subaltern Studies, can also be found in some of the essays by his disciples. But they are laid out at greatest length in his Elementary Aspects, which provides us with another example of the long (and ultimately unsuccessful) struggle to reconcile structuralism and historical materialism. Friendly critics such as Walter Hauser were distressed to find in the work an unmistakable strain of elitist hectoring and a somewhat unsubtle flattening out of the complexity of peasant societies, while nevertheless recognizing Guha’s importance in the renewal of peasant history. There were also issues raised by historians of the longue durée like Burton Stein over whether Guha had not confounded distinct categories such as hunter-gatherers and peasants through his adherence to the logic of binarism.

In the years that followed, Guha’s most influential writings took the form of essays, many of which were collected in a volume entitled Dominance without Hegemony (1997), which argued that the colonial political system in India (unlike the British metropolitan polity) was one in which open coercion outweighed persuasion, and that the Indian state after independence had continued to practice a version of the same nakedly coercive politics. He also developed his somewhat problematic reflections on historiography, which appeared in their final incarnation as a set of published lectures, History at the Limit of World-History (2002). In some of these later essays, we find Guha moving away from his structuralist position to try out other approaches. One of the most successful and widely cited is ‘Chandra’s Death’ (1987), in which Guha presents a very close reading of a small body of legal documents from 1849 in Birbhum, concerning a botched abortion leading to the death of a young woman. Here, we see Guha deploying his intimate knowledge of rural Bengal, as well as his hermeneutic skills dealing with materials written in a ‘rustic Bengali’ possessing an ‘awkward mixture of country idiom and Persianized phrases’. Though interspersed with genuflection to Michel Foucault, these are moments when Guha comes closest to the spirit of Italian microstoria, an approach he never formally engaged with. In contrast, the lectures on historiography take a very different tack, espousing the by-then fashionable Nietzschean critique of the Enlightenment and claims for the superiority of literature to history. We also encounter the introduction and defence of the concept of ‘historicality’ as a manner of re-enchanting the past. This would lead, almost ineluctably, to the last phase of Guha’s career, where he would largely turn to literary criticism written in Bengali and focusing for the most part on the usual suspects of the Bengali literary pantheon.

Unsurprisingly then, over the lifespan of nearly a century, Ranajit Guha’s trajectory was one of many unexpected twists and turns. The ‘biographical illusion’, as Pierre Bourdieu termed it, may call for a neater form of emplotment than what this life affords us. This is despite the fact that we are dealing with someone with a powerful drive, not to career and careerism, but to a more complex form of charismatic self-fashioning in which Guha largely eschewed the limelight, which he left to some of his younger disciples. Perhaps the secretive habits of his early adult years proved hard to shake off. Nevertheless, by choosing the fringes of the academic world, Guha managed to exercise a greater influence than many of those who held the great seats of academic power. In this, he showed that he did indeed have a consummate understanding of politics and its workings.

Read on: Timothy Brennan, ‘Subaltern Stakes’, NLR 89.