This year Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory turns fifty-two, and still that forbidding text, with its pages-long paragraphs and elusive, paradoxical argumentation, has not said everything it has to say. In a recent NLR article, Patricia McManus cited the book’s reflections on the relationship between artistic form and judgments of value in her response to Joseph North’s call for a ‘left literary criticism that would also be a radical aesthetic education, one which aimed to cultivate modes of sensibility and subjectivity that could contribute directly to the struggle for a better society’. That Adorno would have anything to contribute to this struggle is far from given. For many readers, with its conceptual vocabulary that is grounded in the German aesthetic tradition and its belief that philosophy should dictate the terms of art, the book may seem to belong far more to the past than the present. And yet it seems that Aesthetic Theory still has some light to shed on the question of what art can and – perhaps more saliently – cannot achieve in a world no less unfree than it was when Adorno left it.

A striking resonance with NLR’s present discussion of literary criticism can be found in Adorno’s call for ‘the study of those alien to art’. This is Aesthetic Theory’s equivalent of the figure of the ‘ordinary reader’, with whom the criticism of the past decade has, according to McManus, been increasingly preoccupied: the individual who, blissfully unaware of signifiers, discourses and the other paraphernalia of literary scholarship, simply reads what they like, and doesn’t read what they don’t. Is such a figure merely a projection, a symptom of the legitimacy crisis gripping the academy, as Rachel Buurma and Laura Heffernan argue? Or, as Rita Felski, Amanda Anderson and Toril Moi have it, could a better understanding of the ways in which readers actually read be the basis for a criticism more fully engaged with the wider world?

Adorno’s position on this question is typically dialectical. This figure is presented not without a tinge of elitist hauteur: ‘Those who have been duped by the culture industry and are eager for its commodities were never familiar with art’. And yet, their lack of familiarity is said to afford them a clarity that the regular opera-goer, museum patron or literary critic lacks. They are ‘able to perceive art’s inadequacy to the present life process of society – though not society’s own untruth – more unobstructedly than do those who still remember what an artwork once was’. The person who squints at a work of modern art and demands, ‘What’s it for?’, has in this sense, a more lucid view of art’s standing today than the critic does – namely, that ‘nothing concerning art is self-evident anymore…not even its right to exist’.

Insofar as such passages meld a condescending lack of familiarity with those outside the academy to the deep self-loathing within it, they seem to bring together the weaknesses of both sides of the ‘ordinary reader’ debate. But Adorno isn’t out to idealize or to denigrate. His figure is, rather, a critical check on the ‘committed’ art and criticism of his time. Against Benjamin, virtually the only critic of Adorno’s lifetime considered worthy of sustained engagement in Aesthetic Theory, Adorno takes as axiomatic that the democratization of art was a failure. Rather than bringing art to the masses, in Adorno’s view the work of art’s mechanical reproduction simply produced a more refined form of mass culture – see the grumblings around the publishing world that ‘literary fiction’ is simply an elitist marketing designation – while the cultural homogenization of the classes destroyed the coherent and identifiable publics for whom the artwork was intended.

This historicization of the relationship between art’s producers and its ‘consumers’ is a minor component of Aesthetic Theory’s critique of a critique engagé. When seen from the perspective of the individual without artistic sensibility, he argues, it becomes clear that the categories of such criticism are fired from a pistol – launched, that is, without any rigorous conceptualization of what an artwork actually is. Brecht’s dictum that literature should be ‘no less intelligent than science’ and should therefore yield knowledge as true and as actionable as the social and even the natural sciences, appears rather more vulnerable when one imagines explaining it to the non-reader. ‘There is no answer that would convince someone who would ask such questions as “Why imitate something?” or “Why tell a story as if it were true when obviously the facts are otherwise and it just distorts reality?”’, Adorno writes. There is a ridiculousness even to the gravest artworks, he argues, the roots of which lie in the archaic character of ‘the mimetic impulse’. The concepts and categories of political criticism, which fold together the seriousness of the social sciences and the moral urgency of the struggle for justice are, therefore, attractive precisely because they place a fig leaf over the artwork – like the evening dress worn by Kafka’s ape in his address to the academy.

For Adorno, therefore, any attempt to derive moral and political education directly from works of literature is bound to stumble on literature’s ‘non-identity’. It is this claim for the autonomy of the work of art – usually paired with the anecdote of Adorno blanching when bare-breasted student demonstrators stormed his lecture hall – that has tended to furnish charges of political quietism, and, more outrageously, conservatism. But one need only set a few sentences of Aesthetic Theory alongside those of the ‘new aestheticism’ that – spearheaded by George Levine’s Aesthetics and Ideology (1994) – invoked Adorno to call for a return to the art object, against its ‘politicization’ by Foucault, Jameson and Said to see the difference. Certainly, insofar as he insists that the artwork, while obviously a fait social, cannot be deduced from its social circumstances, Adorno is at odds with other strains of Marxist criticism. He also resists, at least in my reading, the left-Nietzscheanism of Deleuze and Guattari, whose characterization of artworks as only one kind of ‘assemblage’ on the ‘plane of immanence’ suggests that artistic techniques and effects (no strong distinction is drawn here) are social practices simply because they take place within society.

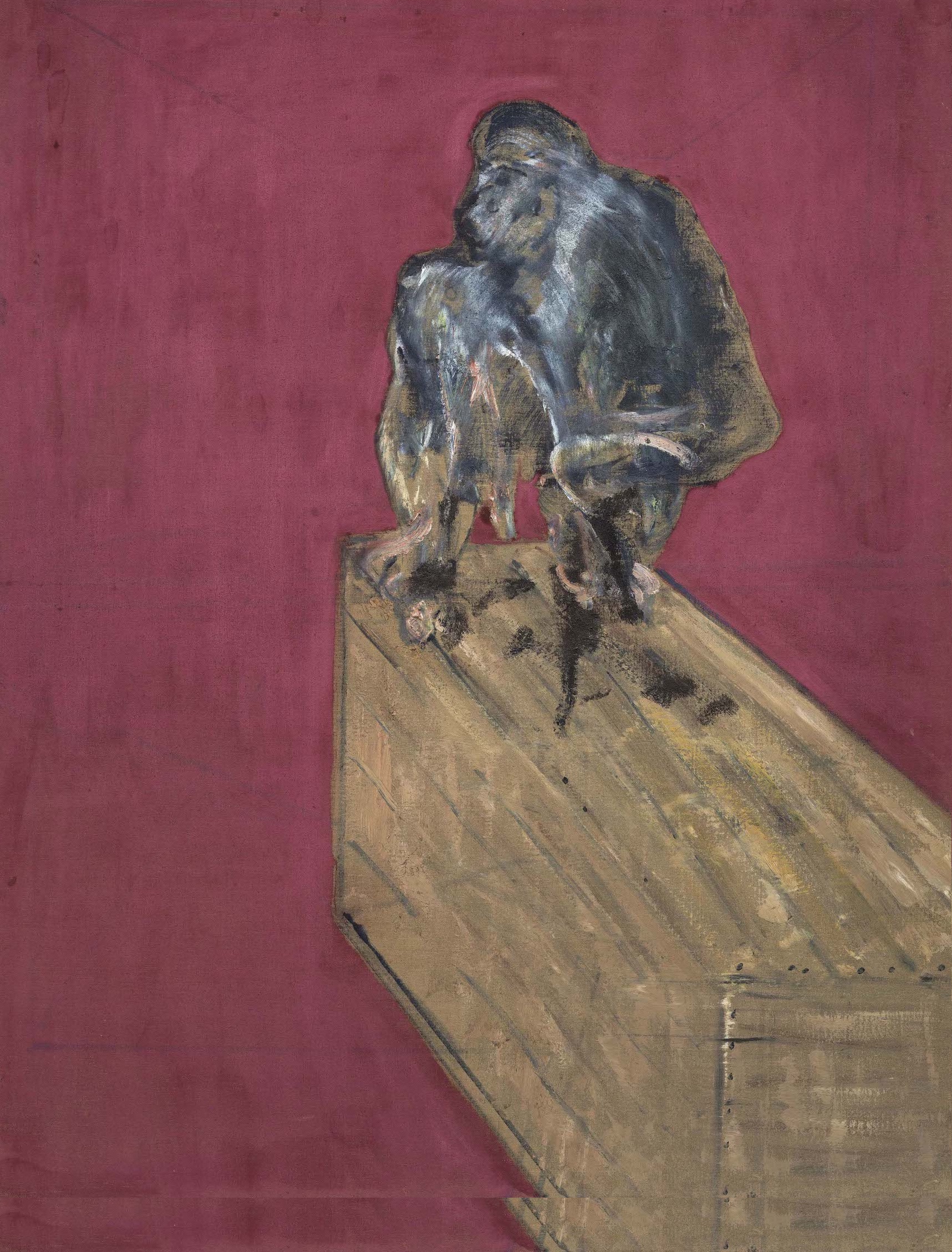

According to Aesthetic Theory, what distinguishes the artwork from the rest of perceivable reality is that it orders its material according to its own logic. In the case of literature, this is most obvious in the transposition of non-linguistic experiences into language. But it is also manifest in the more granular business of style – something considered unworthy of critical attention in the current historicist paradigm. Adorno, however, asserts that art’s social function derives precisely from its distinction from other commodities, modes of production, services and forms of information. The self-imposed rationality according to which the artwork selects and arranges its constituent elements parodies the rationality of the social world. The artwork attains a critical function not in what it says, but in what it does: ‘It accuses the rationality of social praxis of having become an end in itself and as such the irrational and mad reversal of means into ends’. The horrors of technological rationality gone mad – above all, the Holocaust – are never far from Adorno’s analysis of Beckett and Kafka’s ‘negativity’. But even the lightest verse by Eduard Mörike, he argues, has a political character, simply because its elements appear to have come together of their own volition, free of the cruelty with which the social world makes everything within it identical with itself. A left criticism taking its cues from Aesthetic Theory would not, then, endeavour to bring the artwork closer to the social world. Instead, it would seek to move them farther apart.

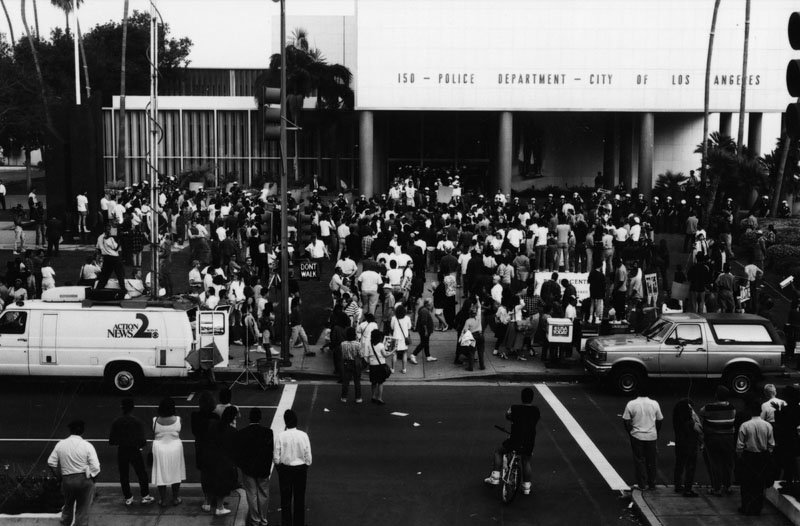

Adorno is, to say the least, elusive about what this would entail. Aesthetic Theory is sparing with its oughts, shoulds and musts. One way to understand the book is as attempting to set limits on other conceptions of the work of art. Aesthetic Theory, indeed, often seems to be inveighing against the paradigms of the present. It is difficult not to read Adorno’s claim, for example, that the technologies, social processes and ideologies without which the artwork could not exist are crystallized within it as a defence of aesthetic experience against the Foucauldian episteme. Its resistance to the total politicization of art, meanwhile, could be addressed to the post-George Floyd American academy. It also voices no small ambivalence about the kind of materialism proposed by McManus, which is understandably gaining currency in a climate of widespread unionization drives by graduate student workers in American universities. In Adorno’s terms, a criticism that would take account of the actually existing material conditions – where there is ‘too much to read, too little time’, as McManus writes – would have to reckon with the displacement of these forces within the object of study for it to be something more than a ‘mere’ sociology of the university and publishing world. Such critical models ultimately retain the same obsession with the reality principle that dominates the administered world – with seeking to ‘punish’ art for claiming to be more than it is by making it less.

It would be no small betrayal of Aesthetic Theory’s unwavering negativity to close with an assessment of its ‘positive’ contributions. Nonetheless, in a certain respect it might be said to converge with North’s view in Literary Criticism (2017) that the coming criticism will place particular emphasis on a ‘therapeutic’ – a word I use advisedly in connection with Adorno – ‘rather than a merely diagnostic use of the literary’. Such an emphasis is, paradoxically enough, apparent in Adorno’s insistence on art’s ‘muteness’, that is, on the way that it transforms discursive ideas and concepts into appearances. Even the most discursive artworks have for Adorno more in common with nature, which simply is, than they do with philosophy or politics. ‘Nature’ refers here not just to natural objects, but to everything dominated, mutilated, and repressed by the civilizing process. The work of art becomes a preserve for those aspects of the world destroyed by instrumental reason, offering a negative image of what Jameson, in his own work on Adorno, referred to as ‘a powerful vision of a liberated collective culture’. Adorno therefore shows himself, in this respect, to have more in common with the emancipatory spirit of the sixties than he let on – though in his view, unlike ‘cuisine or pornography’, art achieves this precisely by suspending the immediate sensation of pleasure (‘Anyone who listens to music seeking out the beautiful passages is a dilettante’). A fully realized aesthetics would not, however, champion a regressive anti-rationalism – whose pitfalls fascism proved once and for all – or a sensory hedonism. In keeping with the Frankfurt School’s original programme, it would work in dynamic tandem with psychoanalysis and anthropology, illuminating all that lies in reason’s shadow, and that is needed to rescue reason in its fullest, most capacious sense from its most determined antagonist – itself.

Such a project is considerably more abstract than that sketched out in McManus’s essay, or, for that matter, than anything criticism has attempted since poststructuralism’s iconoclastic moment. But even Adorno’s most abstract considerations are undergirded by an anguished, ethical commitment. Perhaps Aesthetic Theory’s most significant contribution in the present moment is the centrality of suffering to its problems and its categories. For the rescue of aesthetics does not mean discarding criticism’s moral and political commitments. On the contrary, in an era when art has no clear social function, one justification for its continued existence is its ability to ameliorate suffering. Art is the proper vehicle for grasping and expressing suffering because it ‘eludes and rebuffs rational knowledge’. While today’s engaged criticism all too often elides the distinction between the depiction and reality of suffering – a category error Adorno would have blamed on mass culture – an Adornean aesthetics might situate itself among the ethical paradoxes of the therapeutic artwork. The artwork passes the ‘soothing hand of remembrance’ over human anguish, a relief that contains within it no small measure of betrayal. Criticism can give language to these paradoxes, can tease out and transmit consolation. It can tell us, as politics cannot, what can and cannot be said – what can be changed and what has left its scar once and for all.

Read on: Anahid Nersessian, ‘For Love of Beauty?’, NLR 133/134.