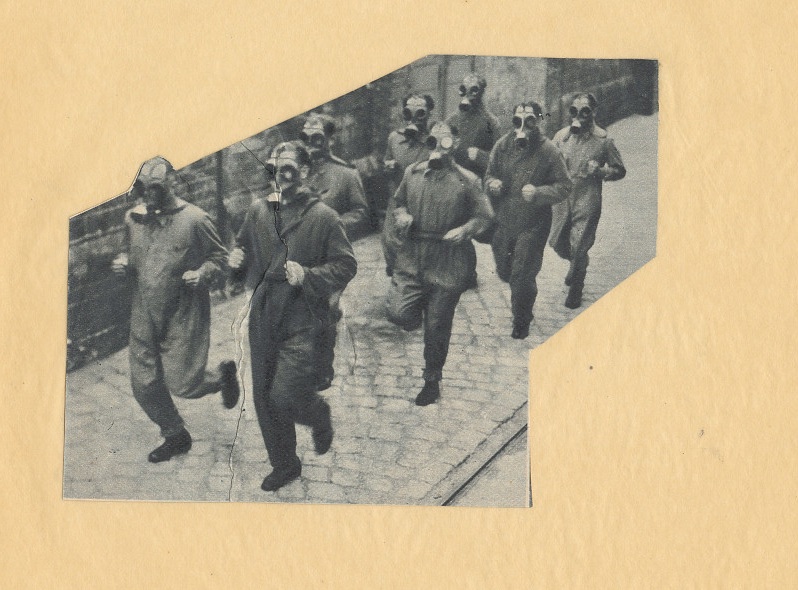

On 28 February 1948 in Accra, the capital of the British colony of the Gold Coast (now Ghana), a group of former servicemen from the Royal African Frontier Force set out with a petition for the governor. They wanted payment of pensions promised them as part of Britain’s war effort. The march was peaceful – the demonstrators were unarmed – but as they approached the governor’s residence in the former Dano-Norwegian slave fort, Christiansborg Castle, they were blocked by colonial police who opened fire. Three demonstrators were killed; several more were wounded. The riots that broke out in response targeted symbols of colonial domination: government buildings were attacked, businesses were looted, and the headquarters of the United Africa Company (UAC, since merged into Unilever) were burnt down. In the aftermath the colonial apparatus – fatally undermined, but destined to stagger on for another nine years – embarked on a programme of reconstruction and repression. Political activists like Kwame Nkrumah were arrested and imprisoned, censorship was introduced. New infrastructure was built.

Chastened by the arson, the UAC commissioned a community centre in Accra from the recently incorporated architecture firm Fry, Drew and Partners, led by the modernist architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry. A photograph of the building’s façade hangs in the first room of the V&A’s Tropical Modernism exhibition (until 22 September). It has many of the design features that characterize Fry and Drew’s work in Britain’s former colonies – what they called ‘tropical architecture’: wide, spreading eaves to create shade; cast concrete brises-soleils to break up sunlight and allow air circulation; pilotis – drawn from the architecture of the Swiss modernist Le Corbusier – for the porch. In the centre is a mural by the painter Kofi Antubam. It shows four geometric figures in traditional dress: three men and a woman. One holds a staff. The woman carries a basket on her head. The figures’ features are not differentiated. Nor are they set in illusionistic space. They are more like grand, generic archetypes than portraits of specific people. The inscription above and below them, written in the local language Ga, translates as ‘It is good that we live together as friends and one people’ – an apt sentiment after a riot.

Accra community centre sums up how ambiguous the links were between modernism and colonialism at this point in mid-century. The British were anxious to defuse ethnic and religious tensions. Antubam’s mural, with its depiction of similar figures standing around conversing, voices a call to peaceful unity regardless of tribal or religious affiliation. The centre was designed to produce such coexistence – within, shady communal areas and a cloistered courtyard allowed people to mingle. Fry and Drew were typical of modernist architects in their belief that intelligent designs, realized in the latest materials, could solve social or economic problems. Architecture, they wrote, ‘should aim at building up a new community life . . . by means of which self-respect and personal dignity may be restored’.

We could see the centre as an instrument of pacification, something brought in by the state-backed UAC to placate a desperate local population. Rather than alter their economic practices, which were a major source of local unrest in the months leading up to the riots (profit margins on company goods were fixed at 75%), the UAC brought in the modernists, to compensate the population with good design for the poverty and isolation that they – the company – had produced.

But we miss something about this building, and about modernism in general, if we associate it purely with colonial oppression. After all, the call to national unity, regardless of tribe or creed, articulated by Antubam in his mural wasn’t only useful for British governors worried about violence against Arab-owned shops. It was also crucial for Ghanaian politicians looking to throw off the colonial yoke – and, after independence in 1957, to hold together the polity’s formerly colonial boundaries. As the first president of independent Ghana, Nkrumah made Antubam an official state artist, commissioning him to design the presidential throne. Nkrumah invested in modernism itself – in the same secular, rationalist aesthetic that the British had employed – as a way to visualize the new state. Room 3 at the V&A provides a record of this investment: photographs of schools, government buildings, the modernist campus at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), the great parade ground at Black Star Square, and the buildings for the Ghana Trade Fair which opened in 1967, the year after Nkrumah’s deposal in a CIA-planned coup.

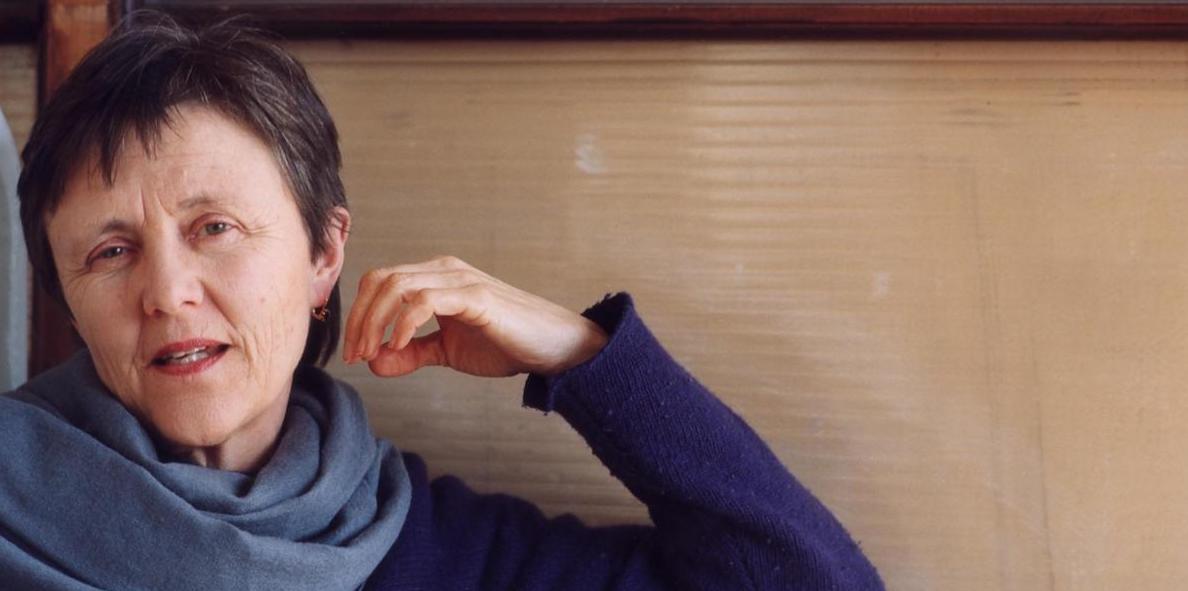

Some of these buildings were designed by Fry and Drew, whose opportunities to create and refine their ‘tropical architecture’ hardly diminished as Britain’s empire broke up. Others were built by their students: in 1954, Fry was put in charge of the Architectural Association’s new Department of Tropical Architecture, where many of the great figures of post-independence Ghanaian and Indian architecture trained. Modernism adapted to decolonization, and vice versa. If Nkrumah’s anti-ethnocentric embrace of modernist design makes him one of the heroes of the show, Jawaharlal Nehru is another. Like Nkrumah, Nehru inherited a state with an ethnically and religiously diverse population, whose boundaries had been arbitrarily fixed by colonialism. Like Nkrumah, he pursued strategies to retain these boundaries that could tip into authoritarianism (India’s occupation of Kashmir is still the longest-running illegal occupation in the world). And like Nkrumah, Nehru recognized architecture’s potential to envision a secular, unified nation beyond divisions like religion and ethnicity – ‘unfettered by the past’, as he put it.

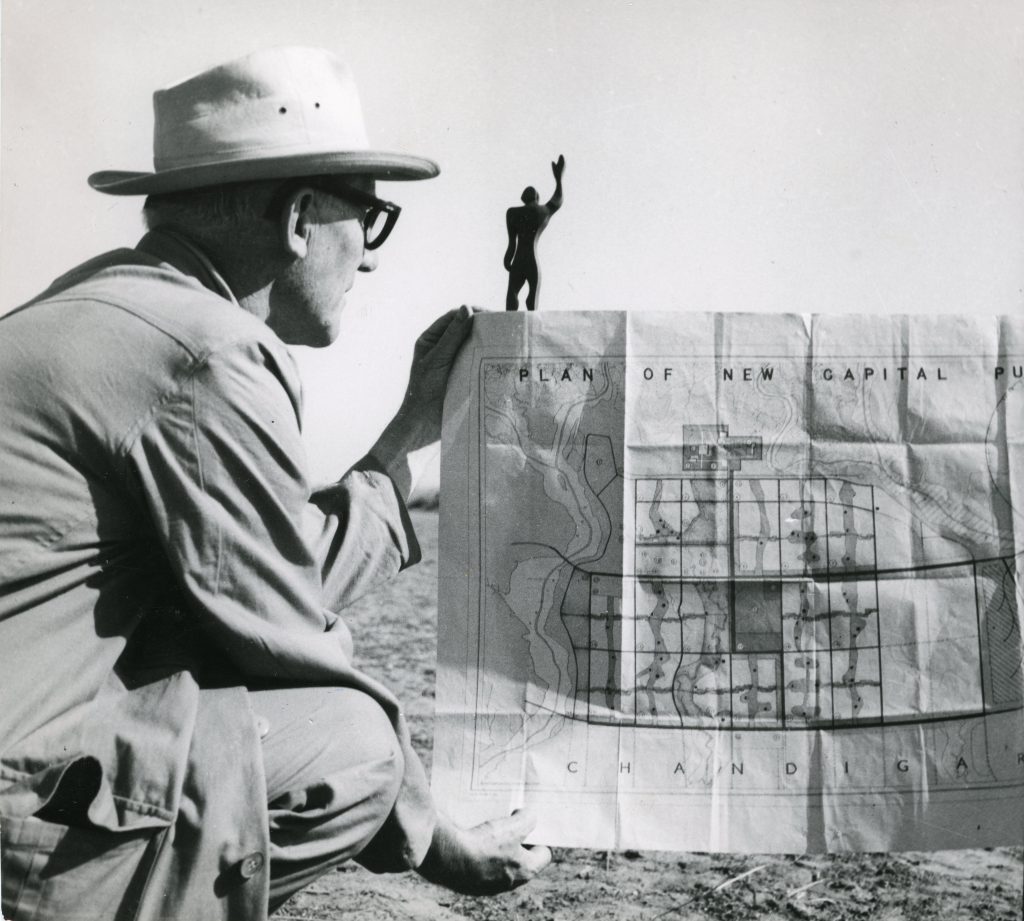

It was Nehru who gave Fry and Drew their most significant commission – the greatest ever imparted to a modernist architect – to build a new capital city for the Punjab, Chandigarh. They convinced Le Corbusier to join the project. He brought in his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret. Chandigarh is the axis round which the exhibition rotates: the ultimate example of tropical modernism in action, a utopic attempt at urban planning on a vast scale, raised against the spectre of violence. Lahore, the previous capital, had been incorporated into Pakistan with Partition. A wall text in Room 2 references the human cost – a million dead, 20 million more displaced – although the curators have decided not to show too much of this. There is nothing of Tyeb Mehta’s rent pictures of bodies twisted and cut in half as if by lightning; nor of Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs of corpses piled in the street.

The closest we come to the horror is Satish Gujral’s anguished painting Mourning en Masse (1952) from his Partition series. This shows four women seated, veiled and moaning. Mouths gape. Eyes are covered. As with Antubam’s mural, they are hardly differentiated from one another, although here the effect of such de-individuation is not one of integrated dialogue, but of grief – of the abject misery that reduces people to wails and shrieks. Gujral’s figures grimace identically. The foremost woman’s left hand is raised, fingerless and cupped, like the blade of a shovel. I am not sure what this gesture was meant to imply – whether the hints I drew from it that the same people, reduced by loss to the condition of interchangeable units, might also make up the labour force to repair the destruction, are due to the picture’s content or to its placement in the exhibition. But this is the effect of Gujral’s painting here, since it hangs alongside so many objects and artefacts testifying to the vast collective effort that produced Chandigarh.

In the middle of the room are two of the iconic, immensely collectible teak and cane chairs made for the different buildings – an Office Armchair designed by Jeanneret and a Library Chair designed by Eulie Chowdhury. Chowdhury was the only woman on the Chandigarh team, responsible for designing a number of buildings including the Government Polytechnic College for Women. The attribution of the chair to her rather than Jeanneret (as is usually the case) represents another small step in recognizing the centrality of Indian architects to the project. The chairs were made from local materials and techniques – a fact that is easy to miss if one dwells for too long on their formal elegance, which seems to speak a language of machines and mass production (this is especially true today, since they have now been copied and mass-produced for sale on the global market). The same holds for modernist architecture in general. The methods by which these buildings were realized, and the traditions to which they appealed, were often drawn from the premodern world, even if their aesthetics strained in the opposite direction. At Chandigarh, as Drew put it rather chillingly, ‘we found . . . that it was easier’ – i.e. cheaper – ‘to use 700 people to excavate than to employ an excavating machine’.

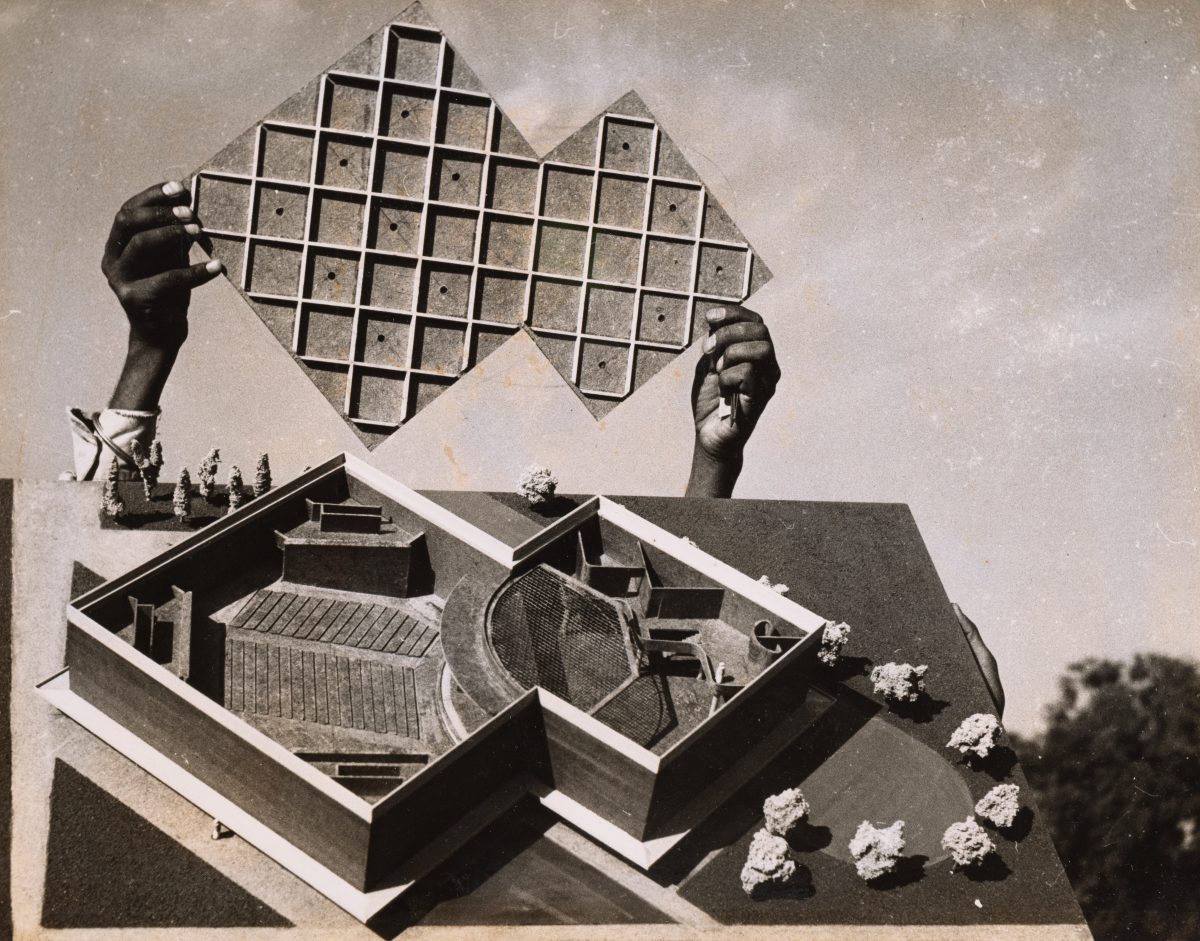

The regular concrete forms, perfect lines and massive, tessellating units of the finished buildings make this fact of their construction difficult to discern. This ultimate modernist project – embodiment of the doctrine of ‘truth to materials’ – belies its own process, the people who made it. One of the loveliest objects in the show is an architect’s model of the Palace of Assembly at the Capitol Complex, done in wood for Le Corbusier by the Sikh model maker Giani Rattan Singh in 1957. Photographs by Jeanneret show him carving the model on site, by hand. The iconic, typically Corbusian steamship-like funnel on the roof is carved from a single block of wood. The model gives us the complex as a geometrical essence – a pure language of volumes and shapes, solid and perfect, devoid of human figures.

The funnel of the Capitol Complex appears elsewhere in the same room, on a screen playing clips from Alain Tanner’s film Une Ville à Chandigarh (1966). The film, documenting the construction of the city, is a corrective to the superhuman purity of Singh’s model, and of the buildings themselves. Against a flat blue sky, labourers form human chains to pass bowls of cement. Women carry the same bowls on their heads. The work is fast and backbreaking. The men sweat through torn clothes. At times the camera pulls back to show the foothills of the Himalayas scattered with peasant dwellings. At others, it cuts to the interior of the new city, where Indian architects in immaculate shirts and ties make drawings. As the camera cuts back and forth – from interior to exterior, from city to outskirts, from half-built skeleton to completed edifice – it becomes possible to make out something of the class antagonisms that went into this ultimate symbol of secular national unity, of the labourers behind the monuments.

Chandigarh’s legacy is still contested. Arguments pointing to the city’s successes – to the high quality of life enjoyed by its residents, the excellent functionality of its public spaces, the generosity of its mass housing – are counterposed to the arrogance and imperiousness of its designers, Le Corbusier in particular. The curators point out his disdain for traditional Indian ways of life, extending to a ban on cows or markets in the city. The architect Aditya Prakash, who worked on the Chandigarh team, came to criticize the city for its commitment to totalizing design at the expense of ordinary human life: ‘it’s a place for gods to play, it’s not for humans’. In two of his own unrealized designs for expansions to the city, abstract people – Indian versions of Corbusier’s Modulor Man – tend market stalls and engage in traditional crafts.

Prakash wanted a modernism more in touch with the needs of ordinary people, more adapted to the Indian context. But the drift of architecture in the years since, towards ethnonationalist postmodern kitsch, would have horrified him as much as it would Le Corbusier. The time of secular modernism is over. India today is living in the age of the mega-temple. The last Indian object in the show is a model of Raj Rewal’s Hall of Nations Complex (1970-74), an interconnected series of capped pyramids made from tessellating triangles of cast concrete. Rewal wanted the complex – which housed the Nehru Pavilion – to echo the achievements of Chandigarh. Its placement at the end of the section is symbolic. The complex was pulled down in 2017 as part of sweeping alterations to the architecture of Delhi carried out under Narendra Modhi’s BJP.

In both India and Ghana tropical modernism is on the defensive, its monuments threatened, their associations with socialism tarnished, their solutions to design problems – whether climactic or political – disregarded. This show tries to reverse the trend. Stress falls on the secularism of modernist architecture, as well as its nascent environmentalism. The application of intelligent design to questions like the creation of breeze and shade by non-mechanical means (Fry and Drew were gloriously scathing about the energy wastage brought about by air conditioning) holds lessons for a heating planet. The effort to produce dignified low-cost housing for all, and to free architecture from the constraints of tradition and religion, are projects for our current age of mass migration and resurgent ethnonationalism. These buildings have been neglected. Sympathetic reassessment should be a first step towards their protection.

Read on: Owen Hatherley, ‘A Mud-Brick Utopia’, NLR 120.