Robert Brenner’s histories of the ‘long downturn’, The Economics of Global Turbulence (1998/2006) and The Boom and the Bubble (2004), are among the most significant conceptualizations of the postwar global economy. A compressed and simplified version of their argument is as follows. Around the turn of the 1970s, downward pressure on prices resulting from new entrants into overburdened manufacturing lines caused falling profitability and investment, leaving the economy vulnerable to exogenous shocks such as the oil crisis of 1973. Keynesian demand-side stimulus was incapable of eradicating such overcapacity and even compounded it. Nor did the subsequent turn to neoliberalism effect a lasting recovery, instead delivering a period of austerity and financialization. This analysis, which anticipated the 2008 world economic crisis and its aftermath, has over the past decade gained increasing traction among both mainstream and heterodox economists. Yet two recent commentaries, by Seth Ackerman in Jacobin and Tim Barker in NLR, appear to challenge its underlying premises. They point to an elective affinity, if not a logical connection, between Brenner’s radical histories and his anti-reformist politics – rejecting the former based on the latter. How valid are their claims, and how compatible is their image of Brenner’s work with the texts in question?

Ackerman

One might expect a critique of Brenner to reconstruct the main arguments in his work and indicate their limitations. Ackerman’s article does not do this. It belongs more to the genre of polemic. The author begins with a primer on ‘crisis theory’, referencing some interesting material on the falling rate of profit from Nobuo Okishio, Paul Mattick and Anwar Shaikh, as well as Capital: Vol. III. He then turns to Brenner’s historical narrative of the post-1973 period, which he claims belongs to this broader Marxist tradition which stresses the centrality of crisis to socialist practice. Ackerman writes that Brenner’s historical approach is motivated by the need to identify unreformable tendencies in capitalism – such as tendentially falling profits – whose existence demands a ‘revolutionary supersession of the existing mode of production’. This position is then dismissed as dogmatic and unjustifiable, or even illogical at a theoretical level. To make this case, Ackerman adduces two major flaws in Brenner’s work.

First, Brenner is said to be reliant on different, mutually exclusive theories of falling profitability, which he deploys as a workaround for the earlier disproven crisis theories of Mattick et al.: a sectoral analysis of manufacturing competition, and a ‘wage-squeeze’ theory which he purports to reject but on which his thesis covertly depends. Second, Ackerman makes the case that the ‘long downturn’ is a myth: that the rate of profit worldwide only suffered a blow during the 1970s and fully recovered thereafter. To the extent that economic difficulties have arisen, he writes, they are simply due to coordination problems: ‘With a far-flung division of labour, the activities of millions or billions of people must be minutely coordinated and anything that disrupts this intricate coordination throws a wrench into the gears of production.’ Let’s consider these claims in turn.

Brenner, as Ackerman acknowledges, is not pursuing a line of argumentation about the tendential fall in the rate of profit. He is making claims about falling profit rates in specific sectors at specific times. For this reason, obviously, criticisms of Okishio, Mattick and Shaikh cannot logically implicate his work. Ackerman’s lengthy excursus on these thinkers, which takes up the bulk of his article, is therefore somewhat extraneous. Yet, more consequentially, Ackerman’s assertion that Brenner contradicts himself by leaning on the wage-squeeze theory is not supported by anything Brenner has written; nor does Ackerman attempt to back it up by way of a relevant citation, let alone quotation. Where might Ackerman have gotten this idea? It appears that it is derived from a misreading of a passage in Brenner’s lecture ‘The Problem of Reformism’ (1993). Here, Brenner states that after the onset of the crisis of profitability, ‘reformist parties in power not only failed to defend workers’ wages or living standards against employers’ attack, but unleashed powerful austerity drives designed to raise the rate of profit by cutting the welfare state and reducing the power of unions.’ It seems that Ackerman has mistaken this uncontroversial description of the class offensive of neoliberalism for an explanation of the ultimate cause of the downturn. That is, Ackerman reads Brenner’s description of employers’ attempts to restore profitability – through austerity and attacks on wages – as an argument about the fundamental reasons for the crisis. One need not agree with Brenner to see that these are distinct. Indeed, for Brenner, the employers’ offensive did not succeed in restoring profitability, partly because it did not get to the source of the problem.

What of Ackerman’s claims, also made by Barker, that the world economy is robust, that the rate of profit worldwide is comparable to that of the Belle Époque, and that therefore the entire basis of Brenner’s hypothesis is fatally flawed? To assess this criticism, it is necessary to begin with an accurate characterization of The Economics of Global Turbulence and The Boom and the Bubble. Both are works of history, not philosophy. The distinction is important, given the tendency of critics to select certain passages from the books and translate them into abstract principles which Brenner is said to hold. In fact, Brenner’s aim is to plot the development over time of the highly contradictory system of global capitalism. The result is not an idealist rendering of axiomatic laws, but the exact opposite: an account of large-scale changes in the postwar global economy, with its many reversals and transformations.

If this is the general method, what are the core historical arguments? Simply put, Brenner claims that Keynesian measures, intended to relieve the problems of overcapacity and overproduction that emerged from postwar industrial competition, ultimately exacerbated them. This failure, evident by 1979, provoked a dramatic macroeconomic reversal. By the turn of the 1980s, the US via the Federal Reserve was attempting to engineer a shakeout (sometimes referred to as ‘neoliberalism’) by raising interest rates to induce a recession. But this, too, failed to restore the world economy to its previous growth rates.

Facing reelection, Reagan resorted to massive spending with a programme of military Keynesianism, followed by an accord with the US’s main industrial competitors to coordinate a devaluation of the dollar to revive US manufacturing exports. But this in turn weakened the manufacturing profitability of the then second- and third-largest capitalist economies, Japan and West Germany. A decade later, in 1995, the advanced capitalist economies engineered a volte-face by way of a revaluation of the dollar. They oversaw the takeoff of finance and dollar-denominated financial assets, including in real estate and the stock market, enabled by ultra-low interest rates. For a period in the 1990s, a recovery appeared to be materializing, with profits in manufacturing rivalling those of the postwar boom. Yet by the turn of the century, first in the East Asian crisis of 1997-98, and finally with the implosion of the dot-com bubble, the so-called ‘new economy’ was shattered.

This is where The Boom and the Bubble and the second edition of The Economics of Global Turbulence leave off. In the long essay ‘What is Good for Goldman Sachs is Good for America’ (2009), Brenner showed that the historic collapse of the world economy in 2008 was an extension of such highly contradictory attempts to resolve long-standing difficulties in the real economy, temporarily achieved through over-leveraged speculation in an inflated housing market. Though originating in the US, the crisis was so large as to be systemic, and required world-historic intervention by central banks globally, lasting a decade or more, arguably down to the present.

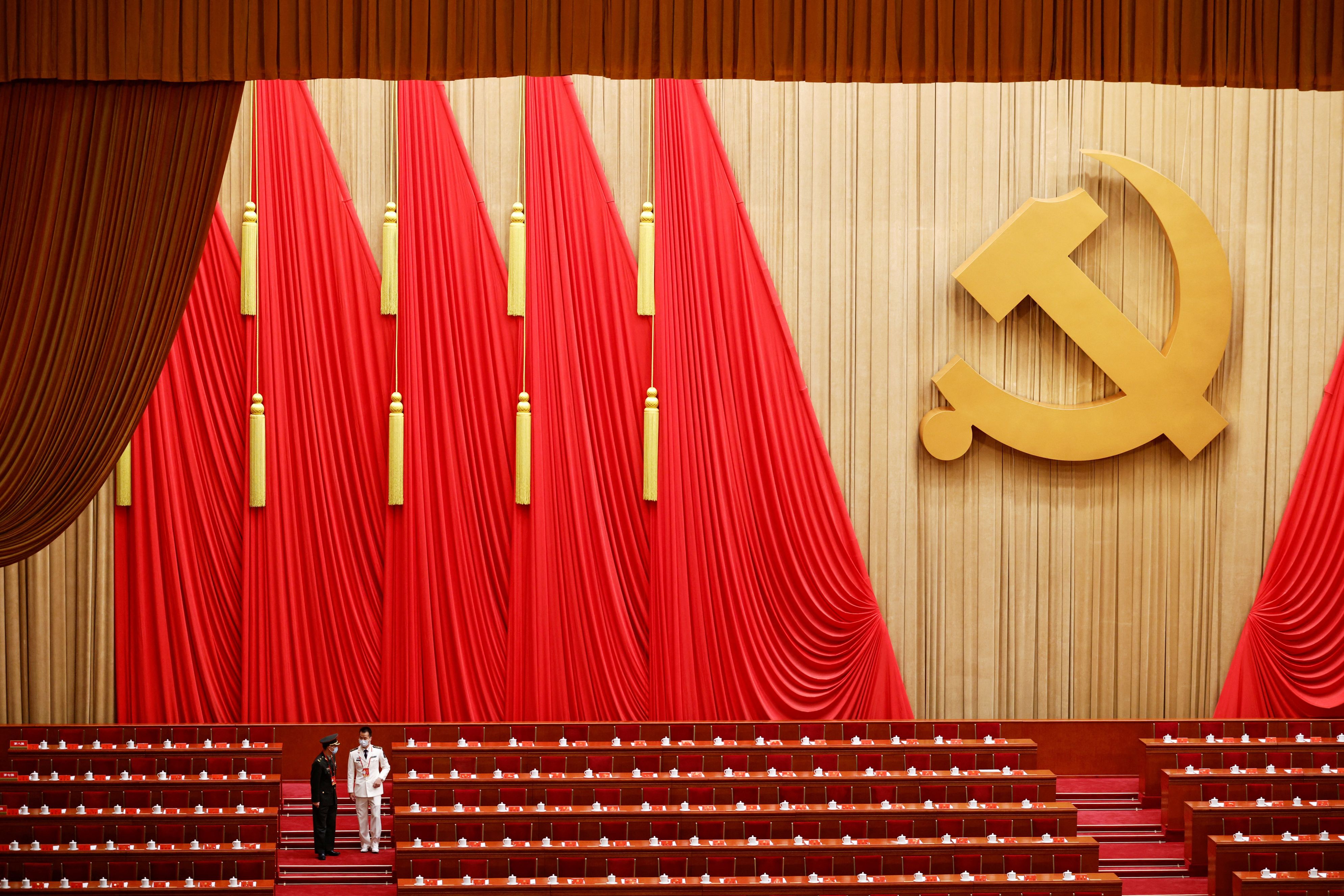

The main point is that after the early 1970s, at each of the turns discussed by Brenner, benefits accruing to manufacturing in one region came at the expense of that sector’s exports elsewhere, while finance tended to benefit from the revaluation of currencies in those same economies. Yet no sustained global recovery of manufacturing ever transpired, and the result was a qualitative transformation of the economy globally: towards financialization in certain zones, with manufacturing dynamism mostly confined to low-wage and high-tech latecomers like the Newly Industrialized Countries of East Asia: the ROK, Taiwan and above all the PRC.

In other words, to the extent that partial recoveries in profitability were achieved, they were limited to certain sectors like finance, at the expense of others like manufacturing. They were also localized, as well as highly dependent on the relative value of currencies. So, for example, finance in the US had a profitable run from 1995 onwards, but in conditions that undermined manufacturing, and by way of massive borrowing. For a time the opposite was true in Germany, but there, short-lived and fragile recoveries were only enabled by the devalued Deutschmark of the late 1990s, and, during the Merkel era, an undervalued euro, plus wage repression, nearshoring of production and the temporarily high growth in export markets like China and Brazil. China, meanwhile, has sustained its dependence on exports by underwriting credit-creation in the US to prop up consumption there. But, as Victor Shih and others have documented, it too has been beset by highly leveraged speculation in its domestic economy. Thus, the fall in manufacturing profit growth detonated a period of turbulence. Each attempt at a resolution – attacks on wages and austerity combined with high interest rates; massive military spending and then low interest rates to encourage successive financial bubbles; coordinated devaluations and revaluations of currencies – had only temporary effect, and set the stage for new rounds of instability.

Is turbulence in the world economy an esoteric diagnosis – one at odds with the scholarly consensus – as Ackerman and Barker appear to think? Hardly. Not just among libertarians, as Barker alleges, but also among his fellow neo-Keynesians, as well as radical historians and social scientists, the general chronology laid out by Brenner is accepted. In the latter category, its adherents range from Philip Armstrong to David Harvey to Eric Hobsbawm to Giovanni Arrighi (author of the most comprehensive critique of Brenner to date). Prominent mainstream economists – including Marcel Fratzscher in Germany, and Larry Summers and Barry Eichengreen in the US – have also developed theories of stagnation that accord with Brenner’s periodization, identifying structural problems in the economy even when it appeared to be firing on all cylinders.

Perhaps most important for the present discussion is Eichengreen’s history of the period, which divides it into two distinct phases: before and after 1973, the year that marked the end of the ‘golden age’ of postwar growth. Eichengreen attributes this to the exhaustion of what he calls the ‘catch-up’ of West Germany and Japan, which, by putting pressure on labour and capital, caused both to abandon their mutually beneficial agreements. What he suggests, and what Brenner plainly states, is that the lack of ‘coordination’ after 1973, which Ackerman argues is the ultimate cause of the slowdown, was in fact prompted by a deeper underlying force. But whereas Eichengreen does not develop his concept of ‘catch-up’ beyond some general remarks, Brenner traces its exhaustion back to the falling rate of profit in manufacturing among the largest capitalist economies.

The potentially most serious objection to Brenner is Ackerman’s calculation of the world profit rate, on which he hangs his principal argument. This metric, undifferentiated by sector and presumably including China, is termed the ‘profit-investment ratio’. By showing little drop-off in total profits, it leaves the coordination problem in the capitalist political economy as the sole cause of the severe crises of the last quarter century. It is an interesting statistical artefact. But because it does not distinguish between manufacturing and the overall rate in the countries on which Brenner focuses, it is not really germane to his argument. It may be that Ackerman’s preferred measure is superior for understanding the rate of profit worldwide in the abstract. But, by itself, it does not address the evidence amassed by Brenner, which documents the depletion of dynamism in productivity growth, output and so on, in specific regions at specific moments – caused by the underlying persistence of overproduction and overcapacity in manufacturing. Even if one concedes that profitability overall, measured however one likes, has indeed recovered, the transformations undertaken in order to accomplish this – financialization, rationalization of production, austerity, deindustrialization – must still be registered as historical developments, along with their political and social implications. This is precisely what Brenner’s work sets out to do.

It is conceivable that a critique of Brenner might begin with the abstract profit-investment ratio; but it could not subsequently dismiss all of Brenner’s work without first considering his detailed history of the period. Unfortunately, that is exactly Ackerman’s approach. For him, there is a more or less continuously high rate of profit throughout the postwar period and across the world economy, punctuated only by ‘coordination failures’ pertaining to the uneven division of labour. Unlike Eichengreen, Ackerman does not account for when or why such issues arise – nor does he explain why, if they are simply due to poor coordination, workers and capitalists haven’t yet brokered an enduring peace to share in the profits which are accruing relentlessly system-wide, and which, under a rationalized coordination of the division of labour, would set society on the path to a brighter future. Such a lasting resolution to class struggle was, in any case, the promise of the mixed economy in the advanced capitalist world around mid-century. Why did this ‘class compromise’ finally end? And why did it end when it did? These are the historical questions that Brenner addresses and Ackerman does not.

Barker

For Barker, Brenner’s focus on manufacturing profitability represents a narrow and selective reading of history, which distorts the overall economic picture of the period. ‘It is not clear’, he writes, ‘why manufacturing profits should be especially important given that manufacturing currently accounts for only 11 per cent of value added in the US economy.’ Is this simply myopia on Brenner’s part? According to Brenner himself, the difficulties in manufacturing constitute the underlying cause which set off the concatenation schematically summarized above. Hence, his focus on the manufacturing profit rate is not due to an arbitrary prejudice, but to what he argues are the empirical and historical origins of the contradictory developments since the end of the 1960s. A critique of this focus on manufacturing, then, should challenge Brenner’s account of the recession of the early 1970s and the subsequent failure of Keynesianism at the end of the decade. But Barker does not attempt this. He simply takes the shrinking share of manufacturing in the overall economy as evidence that the sector, as such, no longer matters as much as it once did. As with Ackerman’s polemic, even if one were to agree with Barker empirically on this point, Brenner’s position cannot be so easily dismissed. For Brenner shows that the turn to finance is a response to difficulties in the real economy. As such, any serious engagement with his work must do more than assert that the real economy is no longer as vital a destination for investment; for this is one of the implications of Brenner’s argument.

Additionally, Barker objects to the concept of ‘political capitalism’ in Brenner’s more recent writing: the idea that, in conditions of stagnation, ‘raw political power, rather than productive investment, is the key determinant of the rate of return’ – and that the state has therefore become an indispensable instrument of surplus extraction. Barker argues that, since capitalism has always relied on state intervention, the novelty of this phenomenon is overstated. But Brenner can hardly be accused of neglecting the role of the state in capitalist development. In The Economics of Global Turbulence, the activities of the US, West German and Japanese states are addressed in nearly every section. What makes this previous period of accumulation distinct from the present one, he argues, is the state’s purpose and orientation. In the postwar period, state intervention organized itself around either increasing the competitiveness of manufacturing or, in the case of the hegemonic US, around encouraging manufacturing recovery in the FRG and Japan. Now, the political sphere is less concerned with ramping up accumulation or coordinating production in competing zones.

Instead, politics has become a process of direct (upward) redistribution of wealth. It is no longer the capitalist state organizing production; it is the ruling class engaging in an amphibious practice of corrupt internal self-dealing, in the context of a system-wide lack of dynamism and weakened ability to produce profits in the real economy. For this reason, it suggests a movement towards a novel mode of production, because it bypasses the specifically economic form of production for exchange that is characteristic of capitalism. Under this emerging regime, the separation of the economic from the social and political is no longer enforced.

Barker’s criticism therefore rests on a basic misunderstanding of the term ‘political capitalism’ in its context. Nothing in Brenner denies Barker’s point about the role of the state in creating conditions for accumulation. The historic shift Brenner identifies is, rather, about the aim of politics and its relation to economics. This is his subject, and although one may disagree with his analysis or terminology, a robust critique would have to confront his argument as it is laid out concretely.

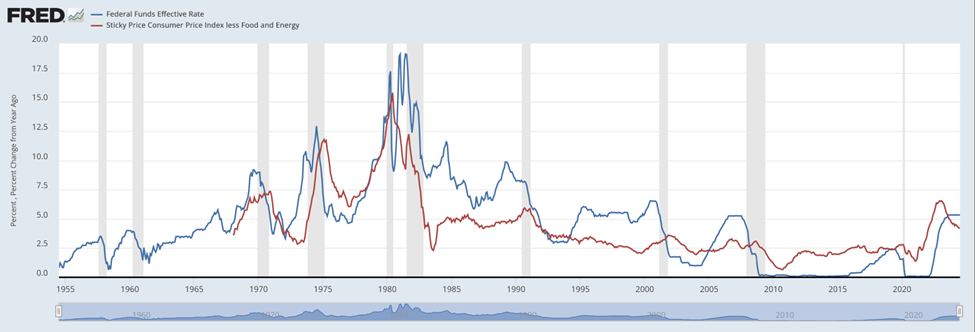

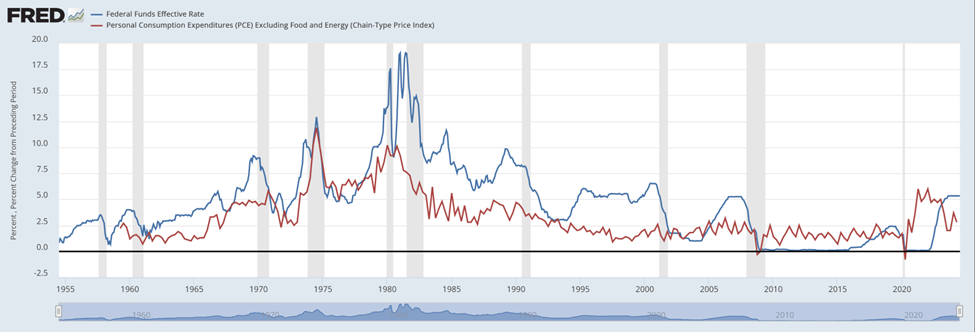

Barker also asserts that Brenner’s analysis of the Fed’s role in the successive bubbles of the last decades is contradicted by the present process of monetary tightening. He claims that the latter is something Brenner theoretically ‘should’ support, given his objection to the cheap credit regime that had characterized the global economy since the 1990s. With this analysis, Barker presents Brenner’s argument as a one-sided criticism of ‘easy money’. But what has Brenner actually written about the use of restrictive versus ‘loose’ monetary policy? One exemplary passage on monetarism from The Economics of Global Turbulence reads as follows:

Ever more restrictive macroeconomic policy was supposed to restore profitability and thereby the economy’s dynamism by undoing the inertial effects of Keynesian debt creation by flushing from the system redundant, high-cost means of production, and by reducing direct and indirect wage costs via higher unemployment. Nevertheless, like Keynesianism, while accomplishing part of what it set out to do, monetarism ultimately proved inadequate, largely because it operated only through changing the level of aggregate demand, when the fundamental problem was over-capacity and over-production in a particular sector, manufacturing, resulting from the misallocation of means of production among economic lines. To the extent that major restrictions on the availability of credit were seriously undertaken, they tended to prove counterproductive, as the sudden, sharp reductions of aggregate demand that they provoked struck over-stocked and under-stocked lines indiscriminately and brought down both well-functioning and ill-functioning firms without distinction. The reduction of aggregate demand also caused problems by making the reallocation of means of production into new lines that much more difficult. In a sense, the problem with monetarism as a solution to the problem of international over-capacity and over-production in manufacturing was the opposite of that with Keynesianism. Keynesianism, by subsidizing aggregate demand, slowed exit from over-supplied lines, but it did create a more favourable environment for the necessarily risky and costly entry into new ones; monetarism, by cutting back aggregate demand, did force a more rapid exit from over-supplied lines, but it created a less favourable environment for entry into new ones.

It is clear from this passage that Brenner sees both ‘easy’ and ‘tight’ monetary policies as incapable of resolving the fundamental contradictions driving the downward pressure on profitability in manufacturing. Each remedy, by responding to only one side of the problem and exacerbating the other, set the stage for a future contraction. Low-interest rates were always destabilizing, politically and otherwise, given the historic level of financial speculation they encouraged. In their wake, the ongoing effort to destroy wealth – mainly that of smaller investors, those who aren’t politically well-connected, and so on – reinforces the ‘political’ nature of the present accumulation regime.

Brenner does not approve of either dynamic, nor should he. He does not argue for higher interest rates as a matter of principle, as Barker – mistaking historical analysis for moral philosophy – contends. He rather shows how in recent decades, low interest rates had been the basis for the wealthy to make money in an economy with little opportunity for profitable investment. The contradictions of that thirty-year regime, which was shaken by 2008 and experienced an afterlife from 2009-19, laid the foundations for the current coordinated class offensive, which Brenner terms ‘escalating plunder’.

The use of extra-economic means of expropriation – that is, coercion – and upward redistribution of wealth are effectively ignored by Barker. But the observable features of the contemporary world economy indicate that something like this is occurring, whether in the dispossession of small property owners or in the prospect of something like a central bank digital currency (CBDC). The latter suggests the direct administration of use values, along with the abolition not just of profit-making in production, but also of money itself as a universal means of exchange and store of value. As Eswar Prasad has written, such digital currencies would be expressly political, since they could be programmed to be conditional for particular uses, and employable only under certain social conditions. By replacing cash, CBDCs may furthermore eliminate the ‘zero lower bound’, and thereby facilitate deeply negative interest rates so as to enable the direct confiscation of deposits in periods of emergency, amounting to a ‘bail-in’ of banks as already assayed in Cyprus a decade ago.

Although these possibilities are not discussed by Brenner, they are now being openly aired by bankers and governments, and deserve serious consideration from the left. In my reading, they confirm his historical narrative, especially in his writings over the last decade and a half. They demonstrate that the primary contradiction today is political; and they account for why, given the weakness of capitalism economically, the ruling class has succeeded in consolidating its power. (Such developments, however, do not preclude a critique of the ‘political capitalism’ hypothesis or the more provocative concept of ‘techno-feudalism’. As Ruth Dukes and Wolfgang Streeck have argued, looking at these claims from a legal-historical perspective, the expansion of freedom of contract distinguishes the contemporary labour market from anything that could be understood as feudal or non-capitalist.)

Reformism versus Reforms

The question of politics is central to assessing the interventions of Ackerman and Barker in another important respect. Both appear to be motivated, more or less explicitly, by the desire to win reforms by appealing to politicians and policymakers, elected and unelected. Ackerman rejects the revolutionary politics that he imputes to Brenner, while Barker attempts to show that legislation like the CHIPS and Science Act in the US should be welcomed by the left. They both object to Brenner’s scepticism of such quasi-technocratic efforts. But Brenner’s historical account of US politics falls by the wayside in their commentaries, which focus instead on his provisional ‘Seven Theses on American Politics’ (co-authored with Dylan Riley) and his lecture on the ‘Problem of Reformism’. Were we to take this longer-term analysis into consideration, how would we then characterize Brenner’s views on the connection between mass politics, political economy and reform in the US?

In his trenchant essay on the 2006 US midterms, ‘Structure vs Conjuncture’, Brenner argues that the most significant American reforms of the twentieth century – those enacted by Roosevelt and later Johnson – were won through militant social movements, each struggling under different political-economic backdrops. Contra the criticisms levelled by Ackerman (and to a lesser extent Barker), Brenner does not attribute these successes to any simple, automatic relation between such movements and the prevailing economic conditions. Rather, he sees their achievements as the outcome of contingent historical developments.

For Brenner, New Deal-era reforms were the result of an ‘explosion of mass direct action outside the electoral-legislative arena’; organizations like the United Auto Workers ‘initially refused to support the Democratic ticket and, at their founding convention in 1936, called for the formation of independent farmer–labour parties.’ Over the course of the ‘second depression’ and defeats in the latter half of the decade, however, ‘CIO officialdom reacted to the fall-off in mass struggles by turning to the institutionalization of union–employer relations, through state-sanctioned collective bargaining and regulation’, which entailed ‘a full commitment to the electoral road and to the Democratic Party’. From this point on, the Democrats and labour officialdom worked in tandem, and came to ‘count on labour’s support’ while delivering less and less in return.

The reforms of the mid-60s in the US – including the Voting and Civil Rights Acts, Medicaid and Medicare – were achieved under an entirely different political economy. The major unions had already been contained and domesticated by their middle-class leaders. Yet the militancy of the black liberation movement, principally in the north, along with the mounting pressure exerted by anti-war and Third World struggles, nonetheless managed to force a series of civil and legal concessions. (The popularity of such reforms quickly established them as hegemonic, and Nixon later sought his own version.)

It was only after the onset of the crisis of the 1970s that the employers’ counter-offensive began, under Carter initially, with deregulation followed by Democratic attempts to secure corporate backers. This went largely unchallenged by pacified trade unions, which had long abandoned any struggle for social reform. Here, Brenner is careful to contrast the trajectories of American and European history:

. . . adaptations to the downturn took place in the context of distinctive balances of class forces across the capitalist north, and this made for a significant variation in politico-economic outcomes. In contrast to the declining rate of unionization in the US private sector, most of the advanced capitalist economies of Western Europe witnessed the opposite trend – an increase in union density not just during the 1950s and 1960s, but throughout the 1970s and, in places, the 1980s.

After 1995, with the appreciation of the dollar amid intensifying inter-capitalist competition, the US economy was largely defined by financialization and offshoring at the expense of manufacturing. US labour was in no position to resist this process, having forfeited its independent political organizations. By 2006, Brenner thought it ‘likely that the Democrats will only accelerate their electoral strategy of moving right to secure uncommitted votes and further corporate funding, while banking on their black, labour and anti-war base to support them at any cost against the Republicans.’ (Pelosi, in due course, funded the war on Iraq, and in the aftermath of 2008, Democrats distinguished themselves as the more enthusiastic partner overseeing the bipartisan bailouts of Wall Street.) Is this history, as Ackerman holds, fatally dependent on ‘crisis theory’, overly suspicious of union bureaucracy, and resistant to pursuing reforms from inside the state?

Ackerman’s assessment clearly fails to capture the detail of Brenner’s analysis, laid out in ‘Structure vs. Conjuncture’, which reveals that reforms can be won under dramatically different political-economic conditions. The comparison with Europe is offered as evidence that, even during periods of crisis, high trade union density could temporarily stave off the massive counter-offensive waged by capital during the 1970s and 80s. The main distinctions drawn by Brenner, then, are not only between different economic conjunctures (booms and downturns). They rather pertain to the history of the left in its concrete social setting – its tactics, class composition, and ability to maintain independence from parties like the Democrats – as it responds to such conjunctures. This is not by any means a historicist argument: it is clear that certain tactics are more useful than others, whatever the wider context; and it is also clear that during downturns and depressions, labour should be prepared for confrontation more than ever. But under any conditions, mobilization of an independent and active mass of the working class increases the likelihood of winning reforms.

In sum, the debate prompted by Brenner’s recent writings might benefit from sharper historical judgment. There is a superficial resemblance between the low-interest rate regime of the turn of the century and the golden age of Keynesian demand management. Likewise, the recent turn to high interest rates and extra-economic plunder may evoke the monetarism that accompanied the employers’ offensive at the end of the 1970s. But the diachronic relation of these episodes demonstrates their specificity. The Keynesian mixed economy dating from 1948 was reversed by the onset of neoliberalism in 1979, and overtaken by the era of ‘bubblenomics’ from 1995. The latter’s failure set in train the emergency neoliberalism of the Geithner-led bailouts after 2008, followed by a decade-long holding pattern. This was, in turn, succeeded by the current ‘political capitalist’ conjuncture: an assault on the population’s living standards combined with a hardening of the state’s repressive apparatuses. This perspective reveals certain causative and determinate links between events as they unfold over time. For that reason, it may be dispiriting to those who hope that the reforms of one era can be transplanted surgically onto another, by way of the correct policy choices. Ultimately, though, a politics rooted in a clear understanding of these distinct historical phases is a more useful guide to the present.

Read on: Robert Brenner, ‘Structure vs Conjuncture’, NLR 43.