In 1992, Hayao Miyazaki visited Hachiman Elementary School to speak to a group of students. This was seven years after Miyazaki had co-founded Studio Ghibli with his peers Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki, four years after the release of My Neighbour Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service, and the same year he would release Porco Rosso. He was a god. The children, all aged eleven or twelve, would have waited patiently for the magic man to appear – perhaps by cat-bus, or insectoid aeroplane, or flying broom. But in he walked with orthopaedic shoes, eyebrows overgrown and hair greying, and reeking, as some naughty adults do, of cigarettes. He briefly introduced himself and then began to talk of death.

In the Jōmon period – the Japanese Neolithic era, around 14,000 BC – people only lived to thirty, he told the class, intimating that he, their hero, would already be dead. In those days, he continued, people died before they became grandparents, and most would have children when they were just fifteen years old! He pointed at one of the students. This was before modern medicine, and so most of these babies would die, and these young mothers would need to have lots and lots of children just to ensure some survived. And even if you make it through all those painful childbirths – no doctors, remember – you don’t get to enjoy life for long, because when you turn thirty your children will be fifteen and it’s time for them to have babies and you to die.

‘Why am I telling you these things?’ he asked the children, presumably all in tears. ‘Well, in winter trees dry up and shed their leaves, but in spring they send forth new buds and shoots. And people are the same, for they have babies, the babies grow up, and then they have their own children. Of course, babies look like their parents, so even as people die they in a sense reappear. Both humans and trees, therefore, seem the same to me.’

Miyazaki’s latest film, The Boy and the Heron, released without fanfare in Japan and currently touring the international festival circuit, is all about life, death, and rebirth. Like any good children’s film, it begins with the protagonist’s mother burning to death in hospital. Mahito Maki, a boy about the same age as those students at Hachiman Elementary, is awoken one night by a civil defence siren, and from his bedroom window sees the fire. He dresses in a hurry – Miyazaki carefully animating the awkwardness of buttoning one’s trousers in a panic, of attempting to speed down a staircase without falling – and then races toward the hospital, now alight with impasto pencil-scratchings in yellow, pink and red. As he runs, people enter the frame as already-charred corpses; they blur and flicker like flames. This horrific vision will recur throughout the film as a nightmare, as will fire – something violent, warm, divine, curative, illuminating, obliterating. (This year’s Oppenheimer, told from the other side of the war, opens with the myth of Prometheus.) In Miyazaki’s films, there is no good and evil, only the products of an oblivious natural world.

Mahito flees Tokyo for the countryside with his father, Shoichi, and his ‘new mother’, Natsuko, whose first interaction with Mahito includes placing his hand on her pregnant belly. He becomes quiet, avoidant, often looking to escape; he gets into a fight at school; he self-harms. All the while a grey heron seems to be mocking him – just circling and swooping at first, later crashing through his bedroom window and shitting all over the floor. ‘Your presence is requested’, the heron says through human teeth. Mahito isn’t sure what this means. He decides to kill the annoying bird by crafting a bow and arrow from bamboo, and in succumbing to malice he inevitably ends up in the underworld.

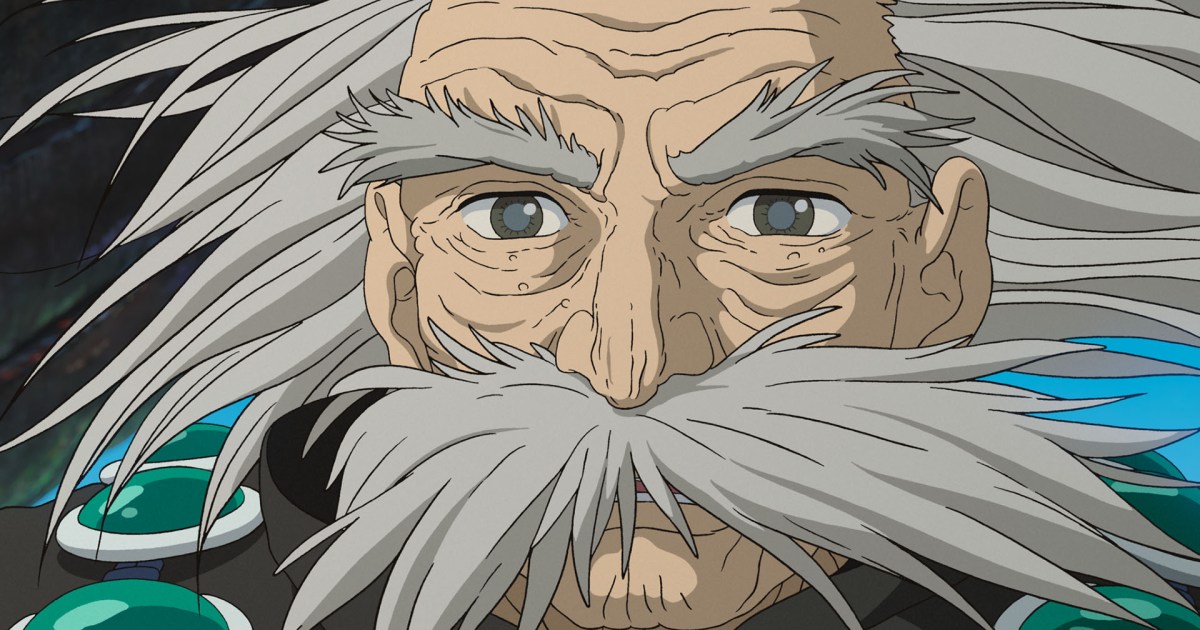

Here there is a milky-eyed wizard who builds the world each day from white marble tomb-stones, carved down to simple shapes, pyramids and columns and spheres, like toy blocks for children. There is an emerging empire of fat carnivorous parakeets who seek to overthrow him. There are little bulbous sperm-ghosts who represent unborn spirits (and will sell well as toys) and there are the vicious pelicans who gobble them up. There is a meteor that shines with the black rainbow of a polished pāua shell from which all the magic of this world is derived. And there is a Charon-like fisherwoman named Kiriko, who rescues Mahito, and who seems to be an age-inverted reincarnation – or parallel-carnation – of one of the goblin-like grannies who watch over him in the ‘real’ world. It’s all very strange.

But I am most taken by the island on which Mahito first arrives. It seems inspired by Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead, and also Dante, featuring a golden gate with an ominous inscription, and Virgil and Ovid, and perhaps most importantly Paul Valéry, whose poem, ‘The Cemetery by the Sea’ where ‘Time glitters’ and ‘Dreams are knowledge’, inspired Miyazaki’s previous film, The Wind Rises (2013):

This peaceful roof of milling doves

Shimmers between the pines, between the tombs;

Judicious noon composes there, with fire,

The sea, the ever-recommencing sea . . .

Miyazaki adapts the poem more literally than before: those ‘milling doves’ are old ships on the horizon, circling the island in a silent, spectral orbit much like the aeroplane graveyard of Porco Rosso. The sun bounces on the ocean’s surface to resemble ‘fire’, a commingling of antithetical elements, which forms a ‘peaceful roof’ for the bodies below. Kiriko warns Mahito to tread softly, lest he wake the dead. (‘Their gift for life flowed out into the flowers! . . . Now larvae spin where tears once formed’ – isn’t this a philosophy of death so like the one Miyazaki recounted to his preteen audience?) The island is an unnerving place and thankfully we don’t stay long. The pair undo their trespassing by walking backwards through the gate. Mahito is told not to look back, like Orpheus, until they reach the shore. The wind is rising, Kiriko warns, and they must set sail at once.

Valéry’s poem ends: ‘The wind is rising . . . We must try to live!’ The recurrence of this phrase – in the title of The Wind Rises, but also within the film, again as a warning to the protagonist – is worth lingering on for the fact that The Boy and the Heron originally took the title of the 1937 novel by Genzaburō Yoshino, How Do You Live? The two films form an answer and a question. Mahito discovers the book by accident one day, a gift from his mother, with a dedication to her ‘grown-up’ boy. We see him abandon reading it to chase the heron. It’s a well-known text in Japanese culture, often read by children, which asks people to act selflessly, lessons of wisdom passed on by an uncle to his fifteen-year-old nephew, Koperu. Miyazaki, now eighty-two, had announced his retirement after completing The Wind Rises in 2013. He first did so in 1997, and has continued this tradition every few years. But after that last film, people believed him. It struck an elegiac tone. Many of its narrative elements were autobiographical, as they are again here: Miyazaki’s father was involved in the manufacturing of aeroplane parts for the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, which the protagonist of The Wind Rises, Jiro, helped design; in The Boy and the Heron, Mahito’s father is seen hoarding aeroplane parts in the countryside to preserve his factory. Miyazaki and his father did flee the war in Tokyo for the countryside (though we can’t be sure that a talking bird changed his life). His mother did get sick, suffering for a long time from spinal tuberculosis – a similar disease to the one suffered by Jiro’s wife – but she didn’t die in his childhood, and instead shocked the family by living well into old age. Mahito is often seen whittling, which is a skill Miyazaki passed on to his son Goro, having learned it from his own father. Jiro is an engineer who dedicates his life to a creative industry which nevertheless harms the world, something Miyazaki feels is true of animation; in The Boy and the Heron, this self-insert is bifurcated between the young Mahito and the old Wizard – the one who has to keep building new worlds else everything will end.

The remedial nature of the wizard’s building blocks gestures to an old-world modality. He draws his power from the meteor, which we learn fell to earth during the Meiji Restoration, an era that marked the end of Japanese feudalism and the beginning of rapid industrialisation. It was a time when samurai were retired and spirits disappeared, when the syncretic, pluralistic approach to spirituality, a mix of Shintoism and Buddhism then called shinbutsu-shūgō, was replaced by the worship of an emperor. Castles were destroyed, deep woods were plundered and railways grew like striped serpents across the countryside, fuelled by coal, whose production rose 3450%. For Miyazaki, as for Timothy Morton, this marked the end of the world. ‘It was April 1784, when James Watt patented the steam engine, an act that commenced the depositing of carbon in Earth’s crust – namely, the inception of humanity as a geophysical force on a planetary scale’, Morton writes in Hyperobjects. The mid-war setting of The Boy and the Heron is no accident, of course. ‘Since for something to happen it often needs to happen twice, the world also ended in 1945, in Trinity, New Mexico, where the Manhattan Project tested the Gadget, the first of the atom bombs.’

Miyazaki is neither Karl Marx nor Ted Kaczynski. He has toyed with socialism and Maoism and now seems to have come around to an ecoterrorism led by nature itself. ‘I’d like to see Manhattan underwater’, he once told a writer for the New Yorker. ‘I’d like to see when the human population plummets and there are no more high-rises, because nobody’s buying them. I’m excited about that. Money and desire – all that is going to collapse, and wild green grasses are going to take over.’ Some of this thinking stems from reading Clive Ponting’s A Green History of the World, which traces the various histories of civilizational collapse brought about by climate catastrophes. (When I saw the empire of parakeets, I thought of Ponting: an invasive species that has repopulated the underworld, risen to power, reached its apex, and in doing so, doomed itself.) It likely influenced Miyazaki’s understanding of societal decadence, his curmudgeonly view that things will inevitably collapse and that this can only mean good things. He even disavows environmentalism for this reason, claiming that his own ecological pursuits – using profits from toy sales to fund rewilding projects, for example – are foremost in the service of a personal nostalgia: ‘When I participated, I felt more pleased by seeing a real crayfish than by some grandiose feeling that I was preserving nature. We were able to become simply happy rather than thinking we were providing aid to protect this or that. We could see that the river was getting closer to what we remembered as children.’

Industrialisation is a childhood’s end, and in Miyazaki we so often see this Promethean moment rendered through a Freudian hermeneutics. (His new film features a primal scene between the father and ‘new mother’, observed by firelight; when Mahito reunites with his biological mother, she’s made much younger; his great transgression in the underworld, which leads to its destruction, is one of ‘taboo’; and so on…) Is Miyazaki a sleeper agent of the Freudo-Marxists, or is this just the nature of children’s films? His producer, Toshio Suzuki, would answer more simply that he’s a ‘mama’s boy’. For the Soviet cartoons that inspired Miyazaki, The Snow Queen chief among them, the child was a symbol that existed outside of capitalism, a pure potentiality or budding revolutionary. In Spirited Away (2001), the young girl Chihiro is the only one in her family capable of seeing spirits, while her parents obsess over consumption and turn into pigs – basically red cinema with a sprinkling of Shintoism.

Miyazaki believes that Mahito’s mid-teen moment is one much like the Meiji Restoration, a maturation that prefigures entry into the labour force and the total deadening of the creative mind (or the spiritual mind, the natural mind – all the same). This is marked most explicitly in Japan by university entrance exams – introduced, of course, during the Meiji period – a time often referred to as shiken jigoku, or ‘exam hell’. (Climb out of the underworld, young people!) This is also the time, Miyazaki claims, when they fall in love with anime. ‘To escape from this depressing situation, they often find themselves wishing they could live in a world of their own – a world they can say is truly theirs, a world unknown even to their parents. To young people, anime is something they can incorporate into this private world . . . The word nostalgia comes to mind.’

Nostalgic for what? A time before adulthood, before industry, pollution, exams, emperors? In Marxism and Form, Fredric Jameson spends a long time teasing out a theory of Marxist literary criticism before arriving at his bravura example-analysis of Hemingway. He calls it ‘a mistake’ to think that Hemingway’s books deal ‘essentially with such things as courage, love and death; in reality, their deepest subject is simply the writing of a certain type of sentence, the practice of a determinate style’. Hemingway, Jameson argues, is attempting to reconstruct some lost lived experience through his prose, where writing is as much a ‘skill’ as bullfighting or fishing. This spiritual pursuit, the nostalgic desire for an old world where the ‘true’ and ‘good’ were possible, is borne out in form, and each sentence points to its creator as an artisan, athlete, hero. Miyazaki’s animation functions similarly. At stake in his work is the anima of all things, the essential lifeforce of a world soon to ‘end in flames’ (so his latest film tells us), which perhaps explains his obsessions with animism, Shintoism and mechanisms of flight – all are a kind of quickening.

Porco Rosso, for example, the story of a porcine fighter-pilot and the closest thing Miyazaki has made to a Hemingway novel, again has little to do with its ostensible themes of ‘courage, love and death’. Few children understand what fascism is or what it means to fight against it, fewer comprehend the geopolitical complexities of aeronautical warfare in the Adriatic, and fewer still catch the reference to Jean-Baptiste Clément’s communard anthem Les Temps des Cerises. But what so enthrals Miyazaki’s audience – as with readers of Hemingway – is the animation itself, which we might liken here to the magic of flight. Consider the propellor, a symbol we find emblazoned on Mahito’s bedsheets: through strict adherence to the scientific properties of aerodynamics (Miyazaki’s insistence on instilling ‘fictional worlds’ with ‘a certain realism’) the propellor spins, blurs and disappears – and in doing so catapults us into the sky. Miyazaki’s unique talent for animating animation has a similarly uplifting effect.

In the 2013 documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, filmed during the making of The Wind Rises, you can see Miyazaki at work. His process is quite simple: he closes his eyes, envisions the scene, then puts hand to paper. Nobody knows what the film will look like until then. Key animation, script and storyboard all arrive at once, direct from Miyazaki’s mind. Here is that old-world modality yet again – the wizard and his building blocks. In his refusal to capitulate to modern technology and his insistence on personally drawing tens of thousands of frames for each film, Miyazaki is equally nostalgic for what Jameson calls ‘nonalienated work’ – but his nostalgia goes further. If previous films lamented the post-industrial use-value of human creativity – be that the ecologically destructive colony of ‘Irontown’ in Princess Mononoke (1997) or the Mitsubishi warplanes of The Wind Rises – then The Boy and the Heron takes a more apocalyptic view. Yes, after the great flood, grasses will inherit the earth, or parakeets, or whatever warriors nature thinks to send, but despite this, humanity will be lost, and human creativity with it. Elephants can paint, just not very well – like most animals they have no eye for colour. So what’s a man to do? In The Boy and the Heron, the wizard is seeking an heir. Will Mahito rise to the challenge? For Miyazaki, the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

Read on: Fredric Jameson, ‘Gherman’s Anti-Aesthetic’, NLR 97.