Some years ago, a friend who lives in Camden Council housing within walking distance from St Paul’s Cathedral told me he’d seen a fox on his way home one evening. This, we agreed, was a landmark. Foxes were spotted in London suburbs for the first time in the 1930s. They made their way into the inner city during the sixties; living in green, hilly southeast London for 24 years, I see them nearly every day. But the dense streets of Central London were still fox-free. And then, they weren’t, and the beasts sadistically hunted by the English upper classes were wandering freely around the very centre of the capital, and can be found stalking the Royal Exchange on the average November night. Urban foxes are among the most conspicuous members of London’s sometimes strange wild animal population. In terms of public fascination, these indigenous beasts rank alongside a much more exotic species: bright lime-green parakeets, who have achieved a similar gradual takeover of the city, suburb by suburb, to the point that they are currently more common – at least in my corner of Camberwell – than sparrows or starlings, nearly as ordinary as pigeons and crows.

Both creatures get their due in the geographer Matthew Gandy’s comprehensive, ambitious Natura Urbana: Ecological Constellations in Urban Space (2022). Gandy has spent the last two decades working on aspects of urbanism that are conventionally overlooked, such as recycling, waste, and most memorably plumbing, the subject of Concrete and Clay (2002), his eye-opening book on New York’s Robert Moses-era water system. He combines this with impatience with neoliberal boosterism (exhibited, for instance, in a ferocious attack on Rem Koolhaas’s praise of excitingly unplanned Lagos). But his most recent book is less a case study than a sweeping, compendious work, focused on the specifically urban nature of ‘urban nature’, and the ways in which accidental and unpredictable interactions of flora, fauna and human beings have taken place within large cities. It is also a timely book; the experience of being locked down in our homes, and finding relief in the exploration of the proximate environment, is still fresh (a phenomenon that has led to the popularisation of the ‘fifteen-minute city’ as both policy and conspiracy theory).

Many people have had unplanned Blakean experiences of finding universes in their local bit of neglected municipal open space – infinities in an allotment, a park, or a back garden. We were locked down as a consequence of the unexpected and ill-thought-out contact among humans, animals and cities; the Covid-19 virus leapt from bats, possibly via expensive, rare trophy animals in Wuhan’s wet markets, to us (another urban anecdote – a friend in the London Borough of Redbridge watching the construction of an impromptu morgue on Wanstead Flats at the height of the virus’s first wave). Both London’s foxes and its parakeets feature in Gandy’s book; he even recounts the delightful urban myth that the parakeets are descendants of birds once released into London’s sky by Jimi Hendrix, rather than, as the more mundane explanation has it, the result of a break-out from Kew Gardens. But much more unusual creatures are just as often the focus – a ‘strange-looking wasp’, for example, that Gandy discovers on his North London window and which turns out to be a member of a rare species (with ‘a liking for dunes, rough grassland and “brambly places”’).

Much of the attention paid to urban nature emphasises its usefulness – urban farms, tree-planting as climate-cooling mechanism and so on. Importantly, Gandy is most interested in an urban-natural landscape that doesn’t ‘do’ anything in particular. Though he concedes that ecology and aesthetics are by no means logically connected, the book is not a study of urban economics or politics (although they do feature) but an attempt to defend a certain kind of urban space created by those evanescent periods in a capitalist economy when one profitable use ends and another has not yet begun; it is essentially a treatise on the virtues of what city planners call ‘brownfield’ (left over by departed industry, property market failure or the effects of war) as opposed to ‘greenfield’ (agriculture, Green Belt, parkland). In trying to create a cosmopolitan, non-nativist ‘reenchantment’ based on the pleasures of ‘brownfield’, he takes issue with a certain urban pessimism that can be found on the left as much as the right; in passing, Gandy mentions his disappointment that the Scottish Marxist geographer Neil Smith’s personal love of ornithology never made it into his critical work on the bourgeois and neo-romantic nature of any project of ‘reenchanting’ space under capitalism.

Natura Urbana’s scope is international. There are detailed excursions to Chennai (home to a thriving community of urban ornithologists), Lisbon (where he finds poplar trees and pampas grass growing around an old gasworks), Yokohama (with its dragonfly-filled ponds), Los Angeles (with its suburban coyotes and parrots) and especially, pre-Wende Berlin, whose wastelands were the subject of a documentary film Gandy made in 2017. But the book is rooted in London, where Gandy grew up in the 1970s. He longingly recalls its bombsites and what used to be derisively called Space Left Over After Planning (SLOAP). In one beloved spot, in his native London Borough of Islington, he recalls a bombsite where ‘bright red cinnabar moths flitted across patches of ragwort, their yellow flowers contrasting with purple drifts of rosebay willowherb, a plant that had become a botanical leitmotif for London bombsites . . . to enter such a space conjured up images from children’s literature, of a magical transition into another world’. This passage recalls Humphrey Jennings’s wartime ponderings on the accidental beauty of bombsites, whose spaciousness and lushness he hoped could inform the practices of post-war planning. But for Gandy it is especially important that this was an ‘accidental garden’, with ‘no planting scheme or trace of human intentionality’ – in 1975, the ten-year-old future geographer wrote a letter to Islington Council protesting the site’s planned redevelopment. Accordingly, this is not a book about consciously ‘designed nature’, though Gandy has some smart and sometimes questionable things to say about it.

(1943). Source: Getty Images.

It isn’t all poetic encounters with municipal scrubland. Some of the urban-natural interactions Gandy catalogues are nightmarish. He describes the cockroach-induced allergies that beset many children in under-maintained American public housing projects, and the mosquitoes that evolved in interwar London to survive in the Underground, sucking on the blood of commuters. He also evokes the terrifying world of the Gilded Age Chicago stockyards, and the modernist slaughterhouses of Argentina (he could have included the Lyon Slaughterhouse designed in the early 20th century by the pioneering modern architect Tony Garnier, or, in Shanghai’s old International Settlement, the extraordinary, proto-Brutalist Municipal Abattoir). But generally the book is affirmative, if unsentimental.

Against the conventional perception of cities as inimical to plants and animals, Gandy insists, surely correctly, that urban areas are in fact very often highly ‘biodiverse’, especially when compared to ‘their monocultural hinterlands dominated by industrialised agriculture’. This is a consequence of the sheer diversity of spaces in cities, and to the sheer quantity, unusual in the more productive parts of the countryside, of places that are left alone. He is therefore enraged by the dismissive term ‘brownfield’. For one thing, these fields tend not to be brown. As an example, he discusses Hauts-de-Seine, the Paris banlieue borough that includes Nanterre and post-industrial Billancourt, whose ‘brownfield’ zones are far more biodiverse than the city’s manicured parks and gardens, comparable to the countryside around. He also finds instances of heavy industry accidentally fostering urban nature as well as destroying it; a vivid case here is the Sheffield-based biologist Oliver Gilbert’s study of the northern city’s wild fig trees, which flourished because the river Don, used for industrial cooling for the city’s steelworks, stayed at 20 degrees centigrade all year round. There’s also Jennifer Owen’s ‘thirty-year investigation of her back garden’ in Leicester, a particularly Blakean endeavour begun in the early 1970s, during which she found ‘over 2,200 species of insects, including 20 that had never been found in Britain and four that were new to science’. This, Gandy points out, is about the level of biodiversity found in Monks Wood in Huntingdonshire, one of Britain’s largest nature reserves; though over time – ironically, as the city has substantially deindustrialised – the diversity of insect life in Owen’s garden has declined.

Gandy’s encomium to the unplanned and overgrown is also a defence of particular plants growing in places where they might be considered ‘foreign’; weeds, wherever they come from, are celebrated here. Much of Natura Urbana is devoted to the ‘non-native’. Examples include the Turkey oak in Britain, hated by conservationists as an aggressive, non-British oak, despite evidence that these oaks were here over 100,000 years ago, before receding and then returning as a consequence of global trade in the 18th century. Gandy speaks up for what are usually described as ‘invasive’, or more heatedly, ‘alien’ plants; most of all for buddleia, the ubiquitous ‘brownfield’ flowering shrub, which is of 19th-century Chinese origin. Just as Asian fauna travelled, usually as a result of imperialism, across Europe and the US, the same process also happened in reverse, like the growth across Chinese cities of sumac plants originally from North America, or the spurges that ‘escaped from the garden of Beijing’s Institute of Botany’ and now grow in the interstices of urban China. This sort of plant life tends to thrive most where systems of management and maintenance have collapsed, though Gandy does not always make the connection. Post-Soviet Kyiv, for instance, he finds to be an especially wild city: by the early 2000s, its 19th-century boulevards and overgrown Soviet ville radieuse housing estates hosted ‘over 500 non-native plant species’. This is undoubtedly true (a photographer and designer of my acquaintance once told me of his joy at coming back to Kyiv after a spell in Vienna – ‘it’s like a jungle!’), but it is a consequence of processes of state abandonment that in other respects have made many people’s lives miserable. Neglect is double-edged, and produces more than buddleia.

The political resonances of the ‘non-native’ species are brought out especially strongly in Gandy’s various tales of Berlin, a city which is returned to again and again in Natura Urbana. Because of the intensity of its wartime destruction and the reservation of an entire continuous stretch of the city as a deliberately fallow ‘death strip’ from 1961 to 1989, Berlin became something like the global capital of ‘brownfield’. It is also, ironically, a city from which Nazi-era botanists, such as Reinhold Tüxen, once attempted to control the vegetation of the Reich according to race science, mapping the vegetation of Germany and Poland according to its degree of Germannness and likening the spread of balsam in rural areas ‘to the threat of Bolshevism from the east’. Gandy devotes much space to scientific attempts to map the city’s post-war wild nature, including Herbert Sukopp’s studies of West Berlin as a place full of what in German is called Brache. Especially intriguingly, he describes Paul-Armand Gette’s 1980s photographs of Berlin streets and tenements overgrowing with shrubs from Peru and North Vietnam as a useful counterpoint to Joseph Beuys’s contemporary proposals for planting 7,000 German oaks in the German urban landscape. Bravely, given Beuys’s enduring (and rather spurious) status as secular saint, Gandy contrasts his nativism, ‘neo-romanticism’ and disinterest in complexity with the much more grounded and egalitarian work of Gette, who was interested in how urban plant life could be at once ‘exotic’ and ‘banal’.

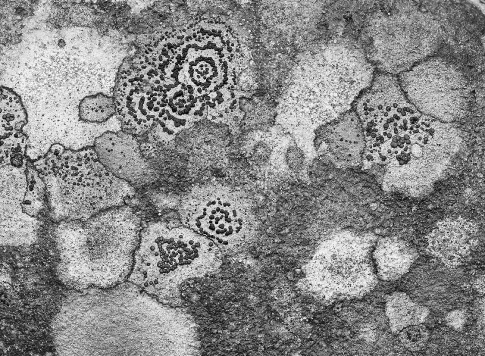

originally from China and North Vietnam, featured in the exhibition ‘Exotik als Banalität‘ (1980). Courtesy of the artist.

Much of this landscape no longer exists, stamped out by the banal stone facades foisted upon Berlin by the neo-Prussian planning regime of Hans Stimmann, but it does survive in pockets. Some of these are unplanned and wild, in the manner Gandy approves of, and are among the city’s most extraordinary spaces, like Teufelsberg, a mountain of rubble capped by the geodesic domes of a derelict CIA listening station, or the ultra-biodiverse wastes on what were once the runways and landing strips of Tempelhof Airport. A few, such as the recently opened Gleisdreieck Park, try to combine the planned and the unplanned. Gandy gives the Berlin examples a cautious welcome, but in general he reserves some of his harshest words for planned urban nature in this otherwise even-tempered book. New York’s High Line, for instance, a linear park on a disused freight line in western Manhattan, he denounces as an ‘ecological simulation’ of what was once a genuinely wild and enchanting landscape, its tastefully selected grasses and pines planted in the service of an extremely successful motor of property development. Gandy gives similarly short shrift to Instagram causes célèbres such as the densely planted ‘vertical forest’ residential towers of the Italian architect and PD politician Stefano Boeri, built in Milan among other cities. These worked well enough in northern Italy, but elsewhere, their spread has fallen foul of exactly the kind of ignorance of the very specific, local character of urban nature that Gandy is trying to outline here. When Boeri’s design was transferred to humid, subtropical Chengdu, the plants covering the skyscrapers quickly attracted dengue-carrying mosquitoes, making the ‘vertical forest’ deeply inhospitable for its human residents and radically reducing the towers’ property values.

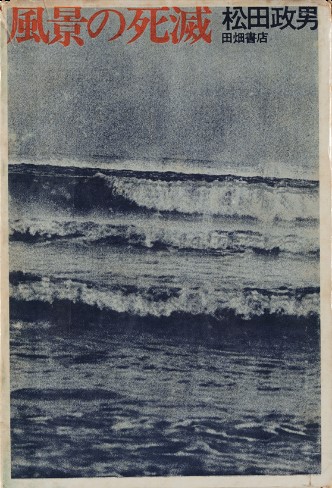

what once existed on the site. Photo by Matthew Gandy.

Like ‘brownfield’ (and for that matter, ‘anthropocene’, a word whose ‘messy omnipotence’ Gandy compares to that of ‘postmodernism’ in the 1980s), ‘Resilience’ is a term Gandy regards with great suspicion. ‘Resilient’ planting in cities tends to entail simple, robust flora, specifically able to weather global warming. This he sees as a new monoculture, in contrast to the constant flux of actually existing urban-natural landscape, the perpetual process of creation and destruction which throws up bizarre and unexpected freaks like the London parakeets. He makes a link between ‘Resilience’ and the mundane practices of neoliberal public management through the example of Sheffield, an especially green large English city, home to those steelwork-induced fig trees. Like ‘Resilience’ planners, the petty outsourcing companies the city charged with maintaining Sheffield’s trees in 2012 have been engaged in a project to replace what were, until recently, ‘fine avenues of elm, lime and cherry trees, some of which harbour rare insects’ with ‘simpler’ streets of little, homogenous, easily pruned varieties. This has led to bitter protests across the city, repeated in the south when a similar bulldozer approach was applied to the post-war boulevards of Plymouth. Disgust at the pruning of the trees helped the Conservatives lose control of that city last year. Gandy cautions that, however justified by the need to counteract global warming, ‘the neoliberal “urban forest” of the future is likely to consist of smaller and younger trees that support far less biodiversity’.

These examples, both glamorous (Boeri’s vertical forests) and shabby (British homogenised tree-lined streets), reveal some of the limitations of planning urban nature. But they are also illustrations of what neoliberalism does in cities. Gandy borrows the term ‘planification’ from Manfredo Tafuri to describe the forces ranged against the unplanned biodiverse urban wastes, but planning is essential to any kind of urban socialism. Given the suspicion of conscious planning that runs throughout the book, there is a question about whether it would be possible to actually create the sort of wild, complex, interstitial spaces that he favours, as opposed to simply waiting for them to emerge through accidents of creative destruction. Gandy surely knows this – his critique of Koolhaas’s dazzled but vacuous reaction to Lagos’s apparent ability to function without planning is among the most powerful attacks on Hayekian urbanism – but seems unable wholly to reconcile municipal socialism with a love of wastelands.

This matters, because conservation can make it perversely difficult to build green infrastructure. Some examples are rural: the construction of High-Speed Rail, for instance, has been made extraordinarily expensive in both Britain and Germany by measures to safeguard landscapes and biodiversity in protected areas – the astonishing cost and endless delays of the ‘Stuttgart 21’ railway project are in part due to the need to resettle thousands of rare lizards whose habitat lay in the path of the high-speed trains, while the preposterous expense of the HS2 disaster in Britain is largely down to ploughing railway tunnels under the Chilterns on routes that would more easily and cheaply run on the surface, so as to leave various southern landscapes untouched. Urban biodiversity is less frequently protected, of course. But a few years ago, campaigners protesting against a council housing development in the London Borough of Southwark, among the borough’s first since the 70s, rechristened the wasteland upon which it was to be built as ‘Peckham Green’. They even managed to get this designation, unheard-of until 2020, onto Google Maps. ‘The intrinsic worth of the ostensibly useless’, writes Gandy, ‘is as much a political question as an aesthetic or scientific one’. Natura Urbana is primarily about understanding and appreciating what already exists; hopefully its many insights will prove useful for understanding what sort of spaces we might want to bring into being.

Read on: Owen Hatherley, ‘The Government of London’, NLR 122.