Petrov’s Flu (2021), the latest film by Kirill Serebrennikov, opens with a depiction of a crowded commuter bus in Russia. The atmosphere is febrile, almost violent. In the grip of a fever, the protagonist suffers a coughing fit and moves to the back of the vehicle. Following closely behind him, another passenger shouts, ‘We used to get free vouchers for a sanatorium every year. It was good for the people. Gorby sold us out, Yeltsin pissed it away, then Berezovsky got rid of him, appointed these guys, and now what?’ He concludes that ‘All those currently clinging to power should be shot’. At this point, the protagonist steps off the bus and enters a daydream in which he joins a firing squad that executes a group of oligarchs.

‘These guys’ refers to Putin and his clique, while ‘now what?’ is a question that weighs heavily on the country they’ve created. What kind of society is contemporary Russia, and where is it headed? What are the dynamics of its political economy? Why did they spark a devastating conflict with its closely entwined neighbour? For three decades, cold peace reigned in the region, with Russia and the rest of Europe swimming together in the icy waters of neoliberal globalization. In 2022, following the invasion of Ukraine and the West’s economic and financial sanctions, we have entered a new era, in which the delusions that animated the country’s market transition have become impossible to sustain.

Of course, the fantasy of post-Soviet development has never matched the reality. In 2014, Branko Milanović drew up a balance sheet of transitions to capitalism, which concluded that ‘Only three or at most five or six countries could be said to be on the road to becoming a part of the rich and (relatively) stable capitalist world. Many are falling behind, and some are so far behind that for several decades they cannot aspire to go back to where they were when the wall fell’. Despite promises of democracy and prosperity, most people in the former Soviet Union got neither. Because of its geographical size and politico-cultural centrality, Russia was the gordian knot of this historical process, which constitutes the vital background to the Ukraine crisis. For beyond the military tropism of ‘Great Power’ approaches, domestic economic factors are at least as essential to map the coordinates of the present situation and explain the headlong rush of the Russian leadership into war.

Period I: 1991–1998

Russia’s aggression is part of a desperate and tragically miscalculated attempt to face up to what Trotsky called ‘the whip of external necessity’: that is, the obligation to compete with other states to preserve a degree of political autonomy. It was this same whip that led the Chinese leadership to embrace a controlled economic liberalization in the early eighties, fuelling forty years of mostly successful integration into the global economy while allowing the regime to rebuild and consolidate its legitimacy. In Russia, however, the whip broke the state itself after the Cold War ended.

As Janine Wedel documents in her indispensable Collision and Collusion: The Strange Case of Western Aid to Eastern Europe (2000), the demise of the Soviet Union resulted in a profound weakening of the country’s domestic elite. During the first years of the transition, the state’s autonomy was minimized to the point that policymaking was effectively delegated to US advisers led by Jeffrey Sachs, who oversaw a small group of Russian reformers including Yegor Gaidar – the prime minister that launched the country’s decisive price liberalization – and Anatoli Chubais, the privatization tzar and onetime Putin ally. Their shock therapy reforms caused industrial involution and soaring poverty rates, inflicting a national humiliation and imprinting a deep suspicion of the West on Russia’s cultural psyche. Given this traumatic experience, the most popular motto in Russia remains ‘the nineties: never again’.

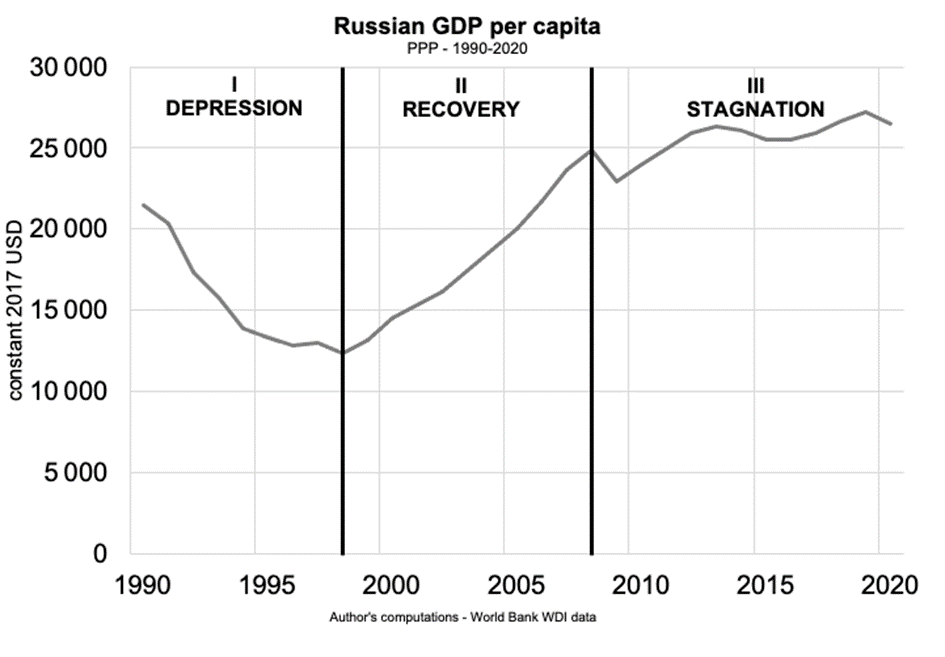

Vladimir Putin built his regime on this motto. A simple look at the evolution of GDP per capita tells us why. The early years of transition were marked by a severe depression that culminated in the financial crash of august 1998. Far from the total collapse described by Anders Åslund in Foreign Affairs, though, this moment in fact contained the seeds of a revival. The rouble lost four fifths of its nominal dollar value; but as soon as 1999, when Putin rose to power on the back of another war in Chechnya, the economy had begun to recover.

Before the crash, the macroeconomic prescriptions of the Washington Consensus had created an intractable depression, as anti-inflationary policies and an obtuse defence of the exchange rate deprived the economy of the necessary means of monetary circulation. Skyrocketing interest rates and an end to reliable wage payments by the state resulted in the generalization of barter (accounting for more than 50% of inter-company exchange in 1998), endemic wage arrears and the exodus of industrial firms from the domestic market. In remote places, the use of money had almost completely disappeared from everyday life. In the summer of 1997, I spent a couple days in the small village of Chernorud, on the western shore of Lake Baikal. The villagers harvested pine nuts and used them to pay for bus fare to the nearby island of Olkhon, as well as accommodation and dried fish, with one full glass of nuts representing a unit of account. The social, health and crime situation was dire. A widespread sense of despair was reflected in the high mortality rate.

Period II: 1999–2008

Compared to this economic catastrophe, the early Putin era was a feast. From 1999 to the 2008 the main macroeconomic indicators were impressive. Barter rapidly retreated and GDP grew at an average annual rate of 7%. Having nearly halved between 1991 and 1998, it fully recovered its 1991 level by 2007 – something Ukraine never achieved. Investment rebounded along with real wages, showing annual increases of 10% or more. At first sight, a Russian economic miracle seemed plausible.

This enviable economic performance was made possible by rising commodity prices, yet this was not the only factor. In addition, Russian industry benefitted from the stimulating effects of rouble devaluation in 2008. The loss of value made locally manufactured goods more competitive, facilitating import substitution. Since industrial enterprises were completely disconnected from the financial sector, they did not suffer from the 1998 crash. Moreover, thanks to the legacy of Soviet corporatist integration, major firms generally preferred to delay wage payments in the nineties rather than lay off their workforce. As a result, they were able to rapidly increase production to accompany the reflation of the economy. The capacity utilization rate increased from about 50% before 1998 to nearly 70% two years later. This, in turn, contributed to productivity growth, creating a virtuous circle.

Another factor was the government’s willingness to take advantage of export windfalls to revitalize state intervention in the economy. The years 2004 and 2005 marked a clear shift in this regard. Privatization was still on the agenda, yet it continued at a much slower pace. Ideologically, the current flowed in the opposite direction, with a greater emphasis on public ownership. A presidential decree of 4 August 2004 established a list of 1,064 enterprises that could not be privatized and named a number of joint stock companies in which the state’s share could not be reduced. State activity was expanded through a pragmatic combination of administrative reforms and market mechanisms. Putin’s most important target was the energy sector, in which he aimed to reassert state control of prices and eliminate potential rivals such as the liberal oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Meanwhile, a combination of new policy instruments and incentives for Russian overseas investment created enterprises that could compete in areas such as metallurgy, aeronautics, automobiles, nanotechnology, nuclear power and of course military equipment. The stated objective was to use funds generated by the export of natural resources to modernize and diversify a largely obsolete industrial base, so as to preserve the autonomy of the Russian economy.

Period III: 2008–2022

One could glimpse a developmental vision in this attempt to restructure Russia’s productive assets. However, strategic mistakes in managing the country’s insertion into global markets, along with strained relations between its political leadership and capitalist class, prevented a proper articulation of this social settlement. The symptoms of this failure became apparent with the 2008 financial crisis and the agonized growth over the following decade. They were first evident in the ongoing reliance on commodity exports – mostly hydrocarbons, but also basic metal products and more recently cereals. Externally, this increasing specialization left the economy susceptible to the fluctuations of global markets. Internally, it meant that policymaking came to revolve around the distribution of an (often squeezed) surplus from these industries.

Russia’s developmental failure could also be seen in its high levels of financialization. As early as 2006, its capital account was fully liberalized. That measure, along with entry to the WTO in 2012, indicated a double allegiance: first, to the process of US-led globalization, whose keystone was the free circulation of capital; second, to the domestic economic elite, whose lavish lifestyle and frequent clashes with the regime required them to stash their fortunes and businesses abroad. Putin encouraged this outflow of domestic capital, even as he simultaneously adopted macroeconomic policies designed to bring foreign investment into Russia. The resultant internationalization of the economy, combined with its dependence on commodity exports, explains why it was gravely affected by the global financial crisis, suffering a 7.8% contraction in 2009. To cope with this instability, the authorities opted for a costly accumulation of low-return reserves – which meant that, despite its positive net international investment position, Russia lost between 3% and 4% of its GDP through financial payments to the rest of the world during the 2010s.

Hence, in the decade preceding the invasion of Ukraine, the Russian economy was characterized by chronic stagnation, an extremely unequal distribution of wealth, and relative economic decline compared to China and the capitalist core. Granted, there have been other, more positive developments. As a consequence of the sanctions and counter-sanctions adopted after the annexation of Crimea, some sectors such as agriculture and food processing benefitted from an import substitution dynamic. In parallel, a vibrant tech sector enabled the development of a digital ecosystem with an impressive international reach. But this was not enough to counterbalance the structural weakness of the economy. In 2018, mass demonstrations against neoliberal pension reforms forced the government into a partial climbdown. They also revealed the increasing fragility of Putin’s regime, which is unable to deliver on its promises of economic modernization and adequate welfare policies. For as long as this trend continues to undermine his legitimacy, the president’s reliance on nationalist revanchism – and its military expressions – will become all the more intense.

Facing economic hardship and political isolation after its adventure in Ukraine, the prospects for Russia are bleak. Unless it can secure a rapid victory, the government will falter as ordinary Russians feel the economic costs of war. It will likely respond by ramping up repression. For now, the opposition is fragmented, and sections of the left, including the Communist Party, have rallied round the flag – which means that in the short-term Putin will have no trouble putting down dissent. But beyond that, the regime is imperiled on multiple fronts.

Businesses are terrified by the losses they will incur, and Russia’s financial journalists are openly sounding the alarm. Of course, it is not easy to predict the outcome of sanctions – yet to be fully implemented – on the fortunes of individual oligarchs. One must note that the Russian Central Bank deftly stabilized the ruble after it lost one third of its value immediately after the invasion. But, for Russian capitalists, the danger is real. Two examples illustrate the challenges they will face. First is the case of Alexei Mordashov – the richest man in Russia according to Forbes – who was recently added to the EU’s sanctions blacklist for his alleged ties to the Kremlin. Following this decision, Severstal, the steel giant he owns, halted all supplies to Europe, which used to make up about a third of the company’s total sales: roughly 2.5 million tons of steel a year. The firm must now look for other markets in Asia, but with less favorable conditions which will damage its profitability. Such cascading effects on oligarchs’ businesses will have implications for the economy as a whole.

Second, restrictions on imports pose serious difficulties for sectors such as automobile production and air transport. A ‘technological vacuum’ could open up, given the retreat of business software companies such as SAP and Oracle from the Russian market. Their products are used by Russia’s major corporations – Gazprom, Lukoil, the State Atomic Energy Corporation, Russian Railways – and will be costly to replace with homegrown substitutes. Attempting to limit the impact of this shortfall, the authorities have legalized the use of pirate software, extended tax exemptions for tech companies and announced that tech workers will be freed from military obligations; but these measures are no more than a temporary stop-gap. The critical importance of software and data infrastructure for the Russian economy highlights the danger of monopolized information systems dominated by a handful of Western companies, whose withdrawal can prove catastrophic.

In sum, there is no doubt that the war in Ukraine will be deleterious for many Russian businesses, testing the loyalty of the ruling class to the regime. But the consent of the broader population is also at risk. As socioeconomic conditions further deteriorate for the general population, the motto that served Putin so well against his liberal opposition (‘the nineties: never again’) may soon backfire on the Kremlin. The mixture of widespread immiseration and nationalist frustration is political nitroglycerin. Its explosion would spare neither Putin’s oligarchic regime, nor the economic model on which it rests.

Read on: Michael Burawoy & Pavel Krotov, ‘The Economic Basis of Russia’s Political Crisis’, NLR I/198.