In the early 2010s, the economist Justin Lin Yifu, a former World Bank chief official with ties to the Chinese government, predicted that China’s economy would have at least two more decades of growth above 8%. He reckoned that since the country’s per capita income at that time was about the same level as Japan’s in the 1950s and South Korea’s and Taiwan’s in the 1970s, there was no reason China could not replicate the erstwhile successes of these other East Asian states. Lin’s optimism was echoed by the Western commentariat. The Economist projected that China would become the world’s biggest economy by 2018, surpassing the United States. Others fantasized that the Communist Party would embark on an ambitious programme of political liberalization. The New York Times’s Nicholas Kristof wrote in 2013 that Xi would ‘spearhead a resurgence of economic reform, and probably some political easing as well. Mao’s body will be hauled out of Tiananmen Square on his watch. Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning writer, will be released from prison’. The political scientist Edward Steinfeld likewise argued in 2010 that China’s embrace of globalization would kickstart a process of ‘self-obsolescing authoritarianism’ resembling that of Taiwan in the 1980s and 90s.

Ten years later, the naivety of these forecasts is apparent. Even before the onset of Covid-19, the Chinese economy had slowed down and entered a domestic debt crisis, visible in the collapse of major real estate developers like Evergrande. After Beijing lifted all pandemic restrictions in late 2022, a widely anticipated economic rebound failed to materialize. Youth unemployment spiked at above 20%, surpassing that of every other G-7 nation (another estimate put it at above 45%). Data on trade, price, manufacturing and GDP growth all point to deteriorating conditions – a trend that fiscal and monetary stimulus has failed to reverse. The Economist now claims that China might never catch up with the US, and it is universally acknowledged that Xi is no liberal, having redoubled state intervention in the private sector and foreign enterprises while silencing dissenting voices (including those that had previously been tolerated by the Party).

It would be wrong to think that external factors have radically altered China’s prospects. Rather, the country’s gradual decline started more than a decade ago. Those who closely analysed the data, beyond the buzzing business districts and flashy building developments, detected this economic malaise as early as 2008. Back then, I wrote that China was entering a typical overaccumulation crisis. Its booming export sector had raked in a huge amount of foreign reserves since the mid-1990s. In its closed financial system, exporters must surrender their foreign earnings to the central bank, which creates equivalent RMB to mop up the foreign currencies. This led to the rapid expansion of RMB liquidity in the economy, mostly in the form of bank loans. Because the banking system is tightly controlled by the party-state – with state-owned or state-connected enterprises serving as the fiefdoms and cash cows of elite families – the state sector enjoyed privileged access to state bank loans, which were used to fuel an investment spree. The result was rising employment, a temporary and localized economic boom, and a windfall for the elite. But this dynamic also left behind redundant and unprofitable construction projects: empty apartments, underused airports, excessive coal plants and steel mills. That, in turn, resulted in falling profits, slowing growth and worsening indebtedness across the main sectors of the economy.

Throughout the 2010s, the party-state periodically undertook new lending in an attempt to arrest the slowdown. But many enterprises simply took advantage of easy bank loans to refinance their existing debt without adding new spending or investment to the economy. These companies eventually became loan addicts; and as with any addiction, increasing doses were needed to generate diminishing effects. Over time, the economy lost its dynamism as zombie enterprises were kept alive through debt alone: a classic case of the ‘balance-sheet recession’ that roiled Japan after its boom ended in the early 1990s. Yet just as these woes became increasingly clear to insiders in the early 2010s, they were censored in official media, which amplified Lin’s upbeat assessment. Meanwhile in the Western world, a web of Wall Street bankers and corporate executives had reason to suppress more sceptical analyses, as they continued to profit off luring investors into China. The illusion of limitless high-speed growth thus ruled the day at the very moment when the economy entered its most serious crisis since the outset of the market reform era.

Beijing has long known what must be done to alleviate this crisis. An obvious step would be to initiate redistributive reform to boost household income and hence household consumption – which, as a share of GDP, has been among the lowest in the world. Since the late 90s, there have been calls to rebalance the Chinese economy in favour of a more sustainable growth model, by reducing its reliance on exports and fixed asset investment like infrastructure construction. This led to some reformist, redistributive policies under the Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao government of 2003–13, such as the New Labour Contract Law, the abolition of agriculture tax, and the redirection of government investment to inland rural regions. But the weight of vested interests (state enterprises, as well as local governments thriving on construction contracts and state bank loans fuelling those projects), and the powerlessness of social groups who stand to benefit from such rebalancing policy (workers, peasants and middle-class households), meant that reformism did not take root. The minimal gains in inequality reduction in the Hu–Wen period were duly reversed after the mid-2010s. More recently, Xi has made clear that his ‘common prosperity programme’ is not a return to the egalitarianism of the Mao era, nor even a restoration of welfarism. It is, rather, an assertion of the state’s paternalistic role vis-à-vis capital: increasing its presence in the tech and real estate sectors, and aligning private entrepreneurship with the broader interests of the nation.

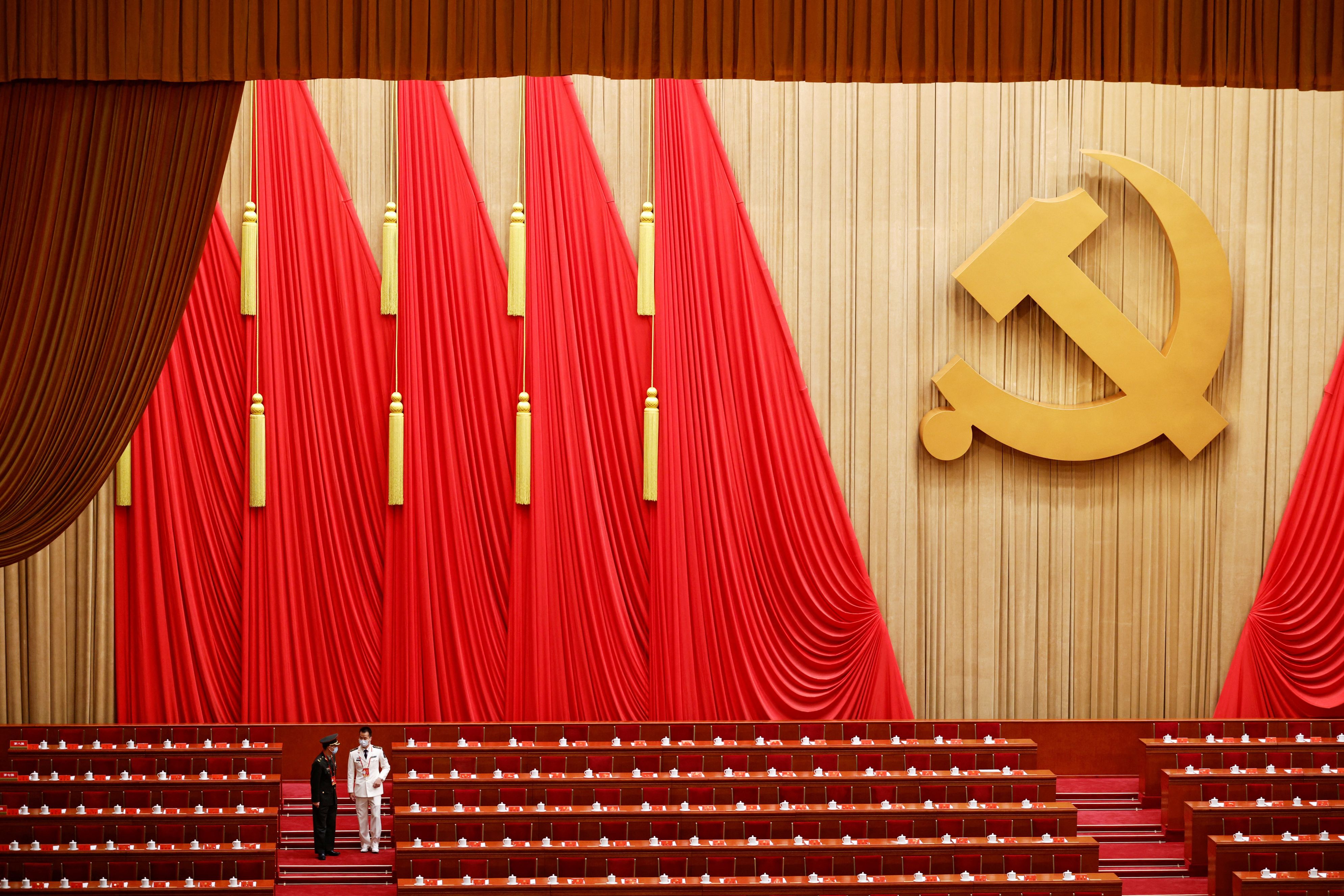

The party-state has been bracing itself for the social and political repercussions of this dire situation. In official policy speeches, ‘security’ has become the most frequently uttered word, eclipsing ‘economy’. The current leadership believes that it can survive an economic downturn by tightening its control over society, eradicating autonomous elite factions, and adopting a more assertive posture on the international stage amid rising geopolitical tension – even if such measures serve to aggravate its developmental problems. This helps to explain the abolition of the presidential term limits in 2018, the centralization of power within Xi’s hands, the relentless campaign to root out Party factions in the name of anti-corruption, the construction of a growing surveillance state, and the shifting basis of state legitimation: away from the delivery of economic growth and towards nationalist fervour. The current weakening of the economy and hardening of authoritarianism are not easily reversible trends. They are, in fact, the logical outcome of China’s uneven development and capital accumulation over the last four decades. This means they are here to stay.

Read on: Nathan Sperber, ‘Party and State in China’, NLR 142.