When I was a child, my mother would read to us from an illustrated version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The content of each page – words in a large well-spaced font followed by a colourful picture – was bordered by bright patterns. Young children are often drawn more to the rhythms of speech than its meaning (their attention seems always to be directed to the conditions which make things possible rather than the things themselves). To the extent that I concentrated on the content of the story, I thought of – and can still partly remember – pictures surrounded by margins so decorative that they threatened to crowd out the main event. I imagined that the margin would grow with each turn of the page, surrounding, constricting and finally overwhelming text and image and, in so doing, bringing about an ending. I thought, or I imagine now that I thought, that perhaps this was the movement which guided the story.

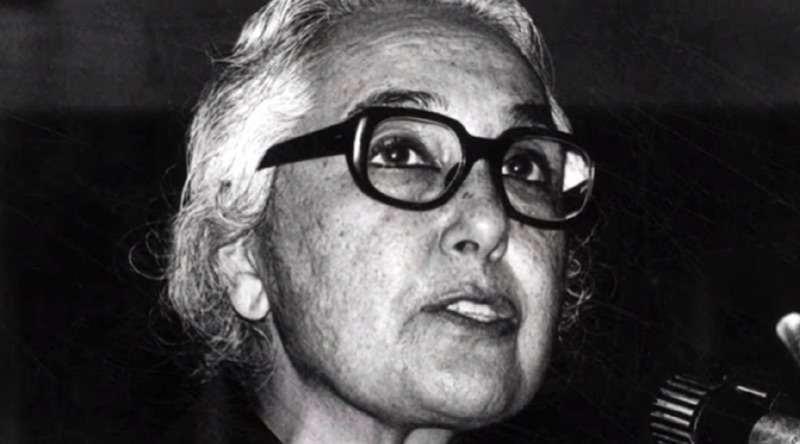

The French filmmaker Alice Diop often refers to her work as an attempt to draw attention to the margins. Marginality does not, as her films make clear, suggest inferior status. It can exist on both vertical and horizontal axes. The closest analogy is psychological: what is marginal is what is not thought about, what is suppressed. The director of six documentaries and most recently Saint-Omer, for which she won the Golden Lion at Venice, Diop is the child of Senegalese immigrants who moved to France in the late 1960s. Born in 1979, she grew up in the Cité des 3000, a district of Aulnay-sous-Bois, a northeastern suburb of Paris built to house migrants working in the nearby Citroën car factory. She studied history, focusing on the legacy of colonialism, at the University of Evry, before training at the prestigious Fondation Européenne pour les Métiers de l’Image et du Son (La Fémis). Like the writers Didier Eribon and Annie Ernaux, she is a transfuge de classe who has dedicated the early part of her career to challenging polite society’s view of the dominated classes.

Conceived as a political project, Diop’s documentary work offered successive portraits of the banlieues that intend to dispel misconceptions and half-truths. Clichy For Example (2006) documents the aftermath of the riots that swept through France after two men died fleeing from the police; Danton’s Death (2011) follows an aspiring black actor, Steve, who dreams of being cast as the lead in the Büchner play after which the film is named, but encounters belittling acts of racially charged dismissal; On Call (2016) presents a series of vignettes set in a refugee medical centre which focus on the psychological and physical difficulties of its patients; Towards Tenderness (2017) examines race, love and masculinity via a set of interviews with young working class men. Most recently, We (2021) saw the director bring herself into the frame, reflecting on the death of her father and the co-existence of modernity and tradition in Paris’s suburbs. Taking inspiration from François Maspero’s Les Passagers du Roissy-Express, a book of photos and prose documenting a journey through the outskirts of Paris which Diop says taught her to love the banlieues, the filmtraverses the city’s periphery without stopping at its centre.

The film marked something of a departure for Diop. Made in response to the Charlie Hebdo attack, We counterposes an image of a France divided between secularism and religious fanaticism with one whose fissures are too subtle to discern. Its scope – monarchists and car mechanics, nurses and game hunters – was wider than anything that Diop had previously attempted. In one scene we see a crowd, entirely white with the sole exception of a black priest, at a mass commemorating Louis XVI at the Basilica Cathedral in Saint-Denis. The camera scans the faces of the attendees. Some are moved, almost to tears, as they listen to the priest read Citizen Louis Capet’s final address. There is something pathetic about the scene, which is shot with an ambivalence that hesitates between disdain or pity. What we see are not those who would once have supported the Vichy regime, but a confused mass descending into the tomb of a dead king that is not kind enough to close behind them. Strange things live on in Paris’s margins.

In what follows, Diop recalls a dream in which she has mislaid the keys to her apartment. She recognizes the names of other residents on the intercom but cannot find her own. Eventually she is let in by a woman to whom she explains that she once lived in the building with her family. From deep in her pocket Diop retrieves a heavy bunch of rusty keys. With force the door yields; she enters, tentatively, and is greeted by a darkness which feels like a ‘tomb’. Unlike the monarchists of Saint-Denis, though, the director wakes up. Video footage of her father recalling his arrival from Senegal now plays. We see him move his face away from the camera and touch it as he speaks – through discomfort at being filmed or the effort of recalling the past? ‘I have always had work since I arrive in France.’ Should we share in his pride or find something melancholy in his assertion of it? Diop again lets the camera linger long enough for a shadow of doubt to be cast over first impressions. Her aim in such scenes is less to challenge a stereotype than, through the slow gaze of the camera, create a space in which the viewer can reflect on the varying meanings of the lives and words of her subjects.

Ambiguity is at the centre of Saint-Omer, Diop’s first feature film and her finest work alongside We. The film is inspired by the trial of Fabienne Kabou, a Senegal-born French woman sentenced to twenty years in prison for the murder of her child. Laurence (Guslagie Malanda), who confesses to the crime but pleads not guilty, confounds jurors and onlookers with her eloquence and psychological opacity. Asked by the judge why she killed her child, Laurence utters a line which will become a refrain: ‘Je ne sais pas’. At the film’s midpoint its other central character, Rama (Kayije Kagame), a black professor of literature who has travelled from Paris to the suburb of Saint-Omer with the aim of writing a book on the trial receives a call from her editor, who asks, ‘What is she like?’ A pause, slight but heavy follows. Whether this is out of exasperation or to collect her thoughts we do not find out, for Rama’s editor quickly supplies an answer: ‘She sounds fascinating’ (To whom?) ‘The press say she talks in very sophisticated French.’ Finally Rama speaks, her voice steady and dismissive: ‘She talks like an educated woman, that’s all.’

Diop’s animating theme is hereby complicated by the fact that Laurence, as with the real-life Fabienne, is in some respects the opposite of an outsider. She comes from a well-off Francophone Senegalese family; we are told that her father is a translator for the United Nations, that as a child she was forbidden from speaking Wolof. (Diop did not speak Wolof at home either and recalls her parents being warned off doing so by her teachers.) That Laurence’s background could count as marginal, that it could make her interest in European philosophy and literature inexplicable and fascinating, is a consequence of the provincialism that Diop sought to expose in We.

The existence of Rama, easily read as a fictionalized version of Diop but probably closer to her image of an ideal viewer, allows the drama of the trial to be seen from a sympathetic perspective. This is in stark contrast to the fetishistic response of the French press, who were quick to treat the real-life events as an expression of ungraspable cultural differences between Africans and Europeans. Rama however is also locked in her own, more familiar drama: a difficult relationship with her mother and her working-class upbringing and the anxiety – fuelled by her pregnancy – that she is at risk of becoming either too close to or too distant from them. In the first glimpse of her personal life, Rama, accompanied by her husband, visits her family. She hesitates when asked by her sister whether she can take her mother to the hospital, before insisting she cannot. At play is not just Rama’s refusal to allow her mother into her life, but the sense that her autonomy has been won by drawing a screen between her upbringing and the life she has made for herself. We are invited to compare the two women: how thin is the line which separates the successful professor and mother-to-be with the woman on trial?

Further details of Laurence’s life are soon revealed. An emotionally distant but disciplinarian mother whom she resents; a kind father that does not raise her but whom she admires; a wealthy family; a bookish, isolated childhood; and an elite class position which places her uncomfortably in French society. Added to this is a relationship with a much older man, Luc Dummontet, with whom she begins an affair not long after arriving in Paris. He is married with children and an irregular presence in her life. When Laurence tells him that she is pregnant with his child he keeps this news to himself, even after the child’s death. Dummontet is frail and pathetic; sheepishly, he complains of Laurence’s jealousy, her anger, her silent treatments, his fear that she will leave him because of his age and declining health.

Rama looks on with compassion, but through Laurence’s plight she is playing out her own fears and anxieties. One night, sitting alone in her hotel room she listens to recordings of the trial. As we hear Laurence speaking about her mother, Rama thinks back to her own childhood. A wordless scene around a kitchen table unfolds. Rama’s mother finishes a drink from a bowl after which she washes it and then retrieves a container of Nesquik from the cupboard, placing it on the table for her daughter who has entered and, without speaking, sits to drink some chocolate milk. The young Rama is wearing pyjamas and her mother is dressed for work; it is dark outside and unclear whether it is early morning or evening. When the camera returns to Rama as an adult her face is heavy with sadness. Is there something in Coly’s sad story that could have relevance to the life of Rama or any other observer?

The latter half of the film attempts, with varying degrees of success, to interrogate this question by treating Coly as a symbol of universal issues of femininity and agency. Laurence tells the court that she was a victim of sorcery, an excuse which the film gives us plenty of reasons to doubt without discounting it. In Saint-Omer’s most unpleasant scene, the police officer tasked with investigating the case explains that in an attempt to provide a cultural explanation for Laurence’s actions he suggested witchcraft. A back and forth ensues between the officer and prosecutor about the difference between infanticide and female genital mutilation, a practice the latter describes as having ‘cultural value’.

To read this scene purely as an instance of racist ignorance and dismissal would be to miss something. The police officer’s fantasies offer Laurence an opportunity to envelope herself in mystery, withdrawing into the symbolic world and becoming someone that cannot be reduced to received social categories. In her final monologue – repeating the words uttered by Fabienne – she explains how, standing on the shore with her child in her arms, the moon rose before her ‘lighting the path like a spotlight’. The judge attempts, unsuccessfully, to point to inconsistencies between this poetic narrative and Laurence’s initial testimony but to no avail – ‘Je ne me souviens pas’, she replies. Evidently, within the world of facts there is no possibility of making oneself intelligible, at least for someone like Laurence.

In her earlier films, Diop was often torn between a desire to depict working class life authentically and angst about the meaning of her images. In the case of Danton’s Death, for instance, she has said that she was careful with her footage lest it might inadvertently reinforce pre-established narratives about working-class men from the banlieues. Steve smoking weed with his friends was left on the cutting room floor: ‘We were not there to reinforce stereotypes but rather to dispel them!’ Rather than careful, sometimes excessive curation of the material, Diop’s solution in Saint-Omer – as in We – is to embrace ambiguity and complexity. But the solution comes at a cost: it runs up against the director’s commitment to a kind of universalism. Two provocative but ultimately contradictory statements made by Diop clarify this: following the release of We she declared in an interview that ‘Cinema makes it possible to test in an extremely sensitive way the existence of the other’; after the release of Saint-Omer, she claimed that ‘the black body carries something universal… I think that all men and women feel some kind of mirroring through this figure of a black woman… that is a political statement.’

The insistence that there are ways of being that cannot be reduced to pre-given frameworks and a desire to show that the particular is in fact universal pull in opposing directions. Saint-Omer responds to this contradiction with a forking path, following one before retracing its steps to follow the other. The first sees Diop granting Laurence the right of indeterminacy. Rama withdraws to her hotel room and watches a scene from Pasolini’s Medea. We watch Maria Callas tenderly dispatch her two children with a blade. They offer no resistance. She opens the window to a moon which lights a path across her face before the camera turns to Rama, stunned with recognition, her face lit by the same glow. A line from Pasolini to Laurence to Rama is drawn – its meaning unclear, its existence indisputable.

The second path is illuminated by a monologue from Laurence’s lawyer, who argues that her client is in need of psychological care. We hear of the chimeric nature of women who, like the mythical beast, are ‘hybrid creatures composed of different animal parts’. Women carry their mothers and their children with them; they live torn between different selves. The camera shifts to the women in the audience, moved almost to tears by this speech. Something like universalism emerges here but the cost of its appearance is never seriously interrogated by Diop. In Laurence’s story there is undeniably some analogy to the condition of women, to some universal – not to say mythic – experience of maternity. But in embracing it, are we not confining ourselves to a binary between ghettoization through racist narratives or universalism offered by empathetic members of the middle classes? Lost in this false choice is the incomprehensibility of Laurence’s actions beyond the poetic drama of her worldview.

Read on: Emilie Bickerton, ‘What’s Your Place?’, NLR 136.