For once, we find ourselves sharing the barely hidden wishes of the Pentagon, White House and entire Western establishment: if only a nice group of boyars could unite in an old-style plot to overthrow Putin and put an end to a war whose objectives remain difficult to comprehend. By boyars I mean the upper echelons of the armed forces or billionaire oligarchs and their contacts in the intelligence and security services; a whole class of potentates who seem ever more uncomfortable with their leader’s adventurism. Yet even if Putin fell and his adventure in Ukraine were halted, an enormous dilemma would persist: the Russia problem. This is something the West has not confronted since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Put simply, what place should Russia occupy in a more or less stable world order? Given the vicissitudes of the past, the small to medium states neighbouring Russia – from Lithuania to Poland to the other ex-Soviet satellites – may hope that it disappears from the geopolitical map. But that isn’t possible.

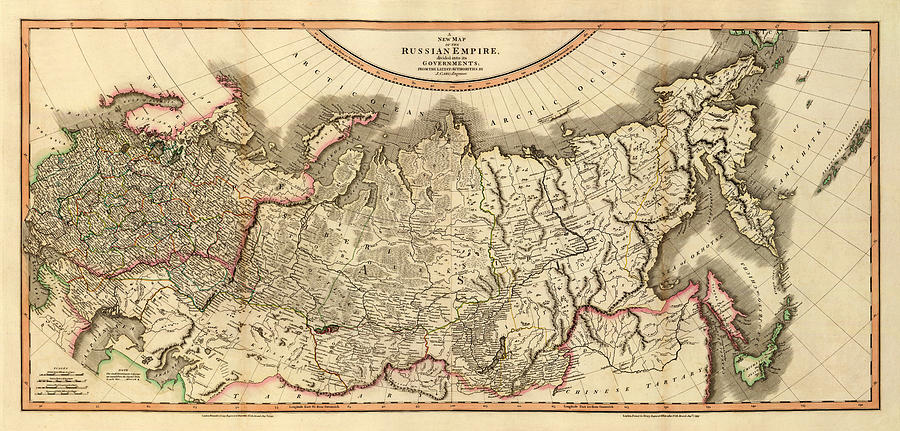

An alternative solution was put forward by Zbigniew Brzezinski when he suggested turning Russia into an assorted bouquet of territories, even advocating for the dismemberment of Siberia: ‘A loosely confederated Russia – composed of a European Russia, a Siberian Republic, and a Far Eastern Republic – would find it easier to cultivate closer economic relations with its neighbours.’ This solution was at the very least problematic due to the presence of China. One look at a map suffices: China, an overpopulated country of 1.4 billion inhabitants, with arable land at a high level of desertification, borders Siberia to its north, an interminable expanse of 13 million square kilometres, home to a population of only 35 million, possessing immense mineral reserves and land that could be rendered fertile with the thawing of permafrost. Demographic pressure alone suggests the future movement of human masses. For the emerging superpower, a weakened and isolated Siberia would be no more than an irresistible mouthful to be devoured – an outcome the United States would find difficult to digest.

In any case, even if amputated, a European Russia would remain the largest state this side of the Urals. In short, our insurmountable problem survives: Russia is simply too big to become yet another American vassal, but too weak to be a world power. Let’s not forget that Russia’s GDP ($1.49 trillion) is inferior to Italy’s ($1.89 trillion), and only slightly larger than Spain’s ($1.28). By comparison, Germany’s GDP is $3.8 trillion, Japan’s $5.1 trillion, China’s $14.7 trillion, and the US’s $20.9 trillion. As Joseph Brodsky wrote in 1976, ‘along with all the complexes of a superior nation, Russia has the great inferiority complex of a small country’.

While the United States failed to recognize the Russia problem in 1991 when it emerged victorious from the Cold War, a similar quandary with Japan was ingeniously resolved after 1945, when the enemy was integrated into the new world order. Of course, Japan was lavished with two atomic bombs to inculcate an indelible lesson – whereas, despite everything, this wasn’t possible with the USSR. In the 1990s the victorious US never found a place for post-Soviet Russia. Now everyone blames the past. In retrospect, a few are willing to admit that NATO’s (and the EU’s) eastward expansion overly precipitous; even a Cold War liberal like Thomas Friedman has written that America and NATO are hardly ‘innocent bystanders’ in the Ukraine crisis.

Noting this might seem like a futile exercise in historical recollection. But it is useful, in such instances, to rethink our relation to the past. Might the massacres, wounds and scars of Partition have been alleviated (and the ascent of Narendra Modi halted) had the framework employed by the British to split India on the basis of religion been critically interrogated? (It’s worth remembering that the first partition took place not in 1947, but 42 years prior in 1905, dividing the majority Muslim East Bengal from the Hindu West). Likewise, given the now century-long state of instability and endemic war experienced by the Middle East, we may also need to re-examine the borders arbitrarily traced and abstracted from the realities of human geography by a British and French official – Mark Sykes and François-Georges Picot – in their apportionment of the moribund Ottoman Empire in 1916.

That remembering the past is no idle task is demonstrated, a contrario, by the fact that at the close of the Second World War, the United States remained wary of a second Versailles, in which the victors of the First World War imposed such oppressive reparations on Germany that the peace resulted in runaway inflation and a revanchist nationalism that would find its expression in Nazism. After 1945 the US never asked Germany for so much as a penny, but rather financed its reconstruction. Nor would it have been remiss to recall, in front of the ruins of the Twin Towers in September 2001, that it was the US that initially sponsored and supported Osama bin Laden.

Here, though, what we need is not necessarily an examination of the past, but an analysis of the failure that persists before our eyes. This failure consists in an inability to construct a Russian entity that might have a place – a function, a voice – in the post-Cold War global order, and the inability of the leading capitalist power to guarantee the stable transition of Russia from a statist economy to a structured market one. A handful of naïve commentators saw in the Russian gangsterism of the 1990s a rerun of the late nineteenth-century American ‘robber baron’ era. But in the earlier case magnates reinvested their profits in America, funding its universities and libraries, whereas all Russian oligarchs have done is export their capital and assets abroad while impoverishing their homeland. In creating a society of gangsters, the US was implicitly asking for Russia to be governed by either a cop or a spy. With Putin, they got both.

Responsibility, however, not only lies with the US: Europe too has not been an innocent bystander. The United States might have failed to reconfigure its empire to accommodate Russia, but it has only grappled with this problem for the last thirty years. Europe has been hesitating about Russia for three centuries. At times it has been invited to the fora of the great European powers – the Congress of Vienna in 1815, for instance – but otherwise it’s seen itself relegated to Asia (especially in considerations of its so-called ‘oriental despotism’, the title of Karl Wittfogel’s famous work). As Alexei Miller and Fyodor Lukyanov observe, ‘for more than three centuries Russia was represented in the European discourse in two ways.’ One is that of a ‘barbarian at the gate’. After the end of the Second World War, Italian anticommunist propaganda incessantly conjured Cossacks watering their horses at the fountains of St Peter’s Square (note that Cossacks have always been identified with Ukraine, ever since Pugachev and Gogol’s Taras Bulba). Today the image of ‘barbarians at the gate’ is as topical as ever. However, the second role commonly attributed to Russia is more interesting. For Miller and Lukyanov, it is

that of an ‘eternal apprentice’. In medieval Europe, the apprentice was entirely dependent on the master craftsman, who was responsible for his instruction. Some were allowed to create and present their own masterpiece for the whole guild to judge its merits and to become a member of the guild in case of approval. In Russia’s case the European discourse invariably insisted that ‘the apprentice is not good enough yet’. The role of an eternal apprentice was (and still is) a trap, where Europe invariably positions itself as an instructor and changes evaluation criteria again and again, thereby perpetuating Russia’s role of a trainee.

This attitude – that of a teacher constantly failing Russia in its exams – is evident in German doubts over whether its Ostpolitik is a normalization of ties or, conversely, the first step towards a new Drang nach Osten. Perhaps Europe should also have figured out long ago the relationship between the Union and its cumbersome neighbour.

Of course, Russia is also a problem for Russians, one that’s fuelled by Russia itself. Just compare the Russian and Chinese reactions to American supremacy. For thirty years, China exercised political restraint (from 1980, when Deng Xiaoping launched his reform programme, to the rise of Xi Jinping in 2012) as it focused on expanding its economy, developing new industrial and technological capacities. Only then did it begin to raise its head. This strategy has also allowed it to make inroads in the field of soft power (by building infrastructure for the Third World, for instance, and establishing extremely robust commercial ties with Africa and Latin America). Military spending was therefore sanctioned by a rise in GDP, and investment was able to focus on cutting-edge technology. Russia, on the other hand, concentrated all its resources in the defence sector and remained an exporter of raw materials in almost every other. China and Russia’s per capita GDP is virtually the same, around $10,000 a year, yet the technological and infrastructural gap between the two is abyssal.

From the perspective of efficiency, there’s no competition between Chinese and Russian state capitalism. The causes of this are perhaps best explained by the longue durée: the virtues of the Confucian tradition in the former, as opposed to the purposeful search for incompetent cadres in the latter (under Brezhnev, functionaries were prized for their defects: their passivity, lack of initiative, willingness to act as ‘yes men’). Another factor has been the enormous brain drain after the collapse of the USSR, which triggered perhaps the greatest exodus of scientists in history, reminiscent of Germany’s during 1930s. The result, so far, has been the emergence of a dominant group that never constituted a ruling class.

Behind each of these causes is another unresolved problem, that of Russian exceptionalism. Usually, when exceptionalism is invoked it’s in reference to the United States, the ‘beacon of hope’, a ‘city upon a hill’ with a ‘manifest destiny’. Indeed, every state that strives for hegemony thinks of itself as exceptional. (We’ll have to come back to this affect. As far as the individual is concerned, given that one’s life is unique, and given that when one’s own life ends all other life ends with it, it’s natural that each of us lives their life as an exception; it’s equally obvious that this exceptionalism extends to, for instance, one’s city: I can’t think of a city in the world, no matter how ugly or rotten, whose citizens don’t feel privileged for being born there, or otherwise lyrically glorify the poetics of the urban agglomeration in which they live. The feeling then grows to encompass an entire region or country of birth. Every homeland is ‘the most beautiful country in the world’. In the end, citizens become victims of their city’s mythology, as members of a state become victims of its national myth.)

The fact is that the French, English and Germans are, in their respective ways, healthy carriers of national exceptionalism (here I mean healthy carriers in the same sense as healthy carriers of HIV). Even the Chinese, who are beginning to dominate the world arena, have built a unique narrative of exceptionalism (which I previously analyzed in these pages). Russian exceptionalism also has a story of its own. With good – or more often bad – reason, every nation has monopolized a specific quality of the human spirit: the United States have appropriated dreams (‘the American dream’); the British, humour; France, refinement (l’esprit de finesse); Germany, order (‘German discipline’); Italy, creativity; Spain, pride…

But only the Russians have gone all in with their revindication of the totality of this spirit; the ‘Russian soul’ (Russkaia dusha), that is to say. Dostoyevsky was its standard bearer (‘the Russian soul embodies the idea of pan-humanistic unity, vsechelovecheskogo uedineniia, of brotherly love’). In his Pushkin Speech (1880), he loses it completely:

To become a true Russian, to become fully Russian (and you should remember this), means only to become the brother of all men, to become, if you will, a universal man. (…) I believe that we – not we, of course, but our children to come – will all without exception understand that to be a true Russian does indeed mean to aspire finally to reconcile the contradictions of Europe, to find resolution of European yearning in our pan-human and all-uniting Russian soul, to include within our soul by brotherly love all our brethren. At last, it may be that Russia pronounces the final Word of the great general harmony, of the final brotherly communion of all nations in accordance with the law of the gospel of Christ!

Tell that to the Ukrainians currently under Russian bombardment.

The truth is that none of the great Russian writers of the nineteenth century escaped the clarion call of the Russian soul. Even Europhile Turgenev (who spent most of his life abroad) had the most sympathetic character in his novel Rudin (1857) exclaim: ‘Russia can do without each of us, but none of us can do without her. Misfortune on those that think otherwise, and again misfortune on those who live outside Russia… outside of national temperament there is no art, there is no truth, there is no life… nothing!’

The irony of Russkaia dusha lies in the fact that the concept of ‘a people’ as an individual, with its own personality, is a German one imported from Herder, and the idea of a collective, universal soul is lifted verbatim from Schelling. Russian unity is expressed in a German concept! The Russian innovation was to add an adjective that had until then not been thrusted onto any other nation – Holy Russia (comparable only to Israel’s chosen people). The Russian soul subsequently became a European fashion, spread by the love for Dostoyevsky, at least until the 1930s, when D. H. Lawrence looked with disgust on ‘these self-divided gamin-religious Russians who are so absorbedly concerned with their own dirty linen and their own piebald souls we have had a little more than enough’. Today, ‘Holy Mother Russia’ has resurfaced.

The reactionary character of these conceptions cannot be stressed enough. One of the most ominous long-term effects of this war is that it legitimates – through the destruction magnanimously offered up by the holy Russian soul – the recrudescence of nationalism in Europe, as if the history of this continent needed any more nationalisms.

To think that the first great writer to evoke Russkaia dusha was Gogol, a Ukrainian. Contrary to what Herder thought, an ethno-linguistic community does not at all implicate belonging to a single state, or a single people. The German-speaking Swiss want nothing less than to become Germans, like the great majority of Austrians. The best example of this is Spanish-speaking Latin America, where nations that share a language and a common culture have frequently waged war on one another. The best post-Soviet Ukrainian novel I’ve read, Death and the Penguin (2001), was written in Russian by Andrei Kurkov, who happens to be a strong supporter of Ukrainian independence.

Translated by Francesco Anselmetti.

Read on: Tony Wood, ‘Collapse as Crucible’, NLR 74.