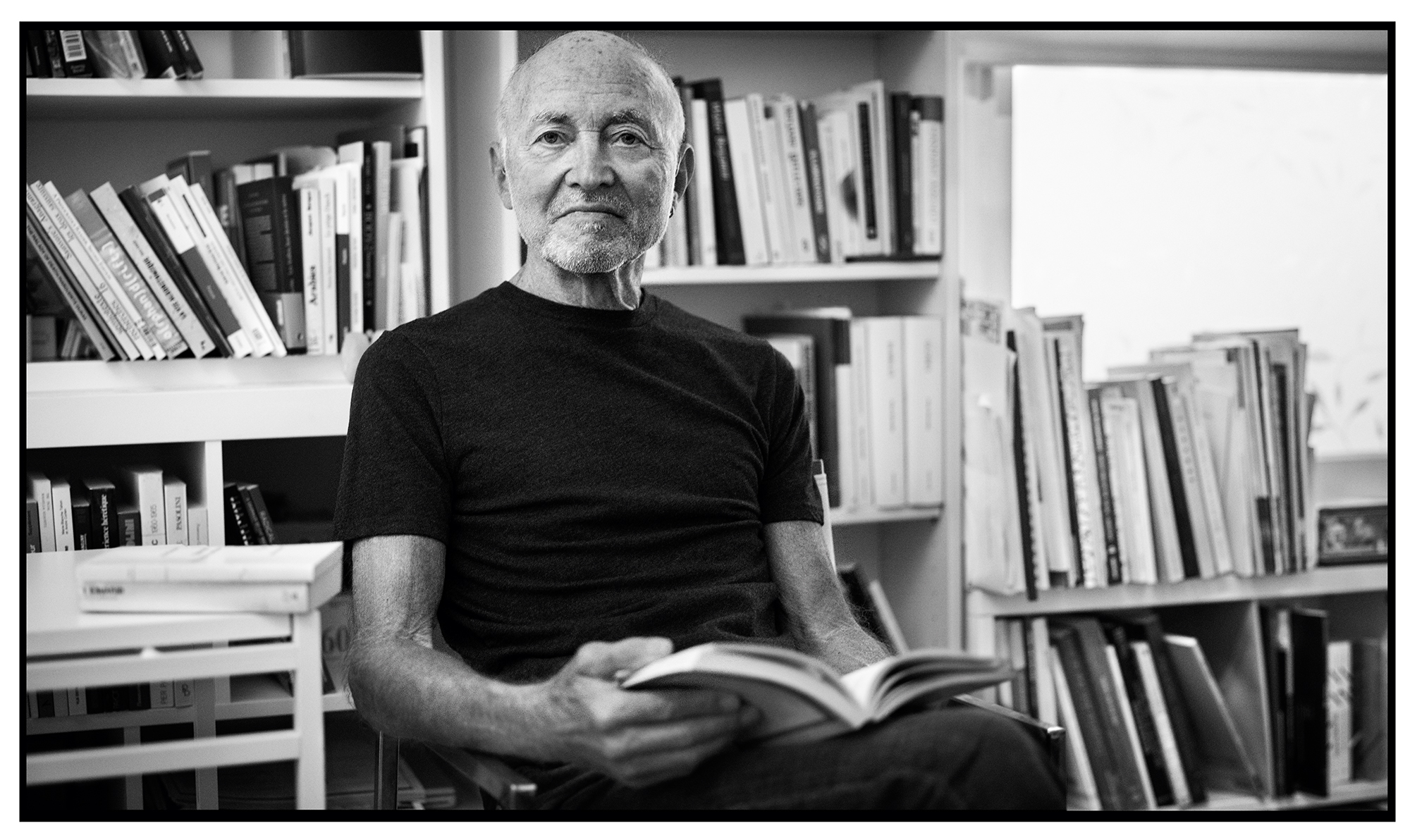

It was a celebration of all the aspects of New York art and culture that Sylvère Lotringer had touched. November 2014: ‘The Return of Schizo-Culture’, staged under the dome at MoMA PS1. It marked the fortieth anniversary of the press Lotringer co-founded: Semiotext(e). Performers ranged from the musician John Zorn to the poet John Giorno.

Lotringer resisted thinking of Semiotext(e) as an avant-garde, but it certainly bears comparison to some of the historic ones. Maybe he reinvented their form or found a way to replace them. Semiotext(e) was certainly more than a publishing house. It was international, inter-generational. It combined workers in many media, who attempted to articulate their time in forms appropriate to it – and whose desires were to change life, or at least endure it.

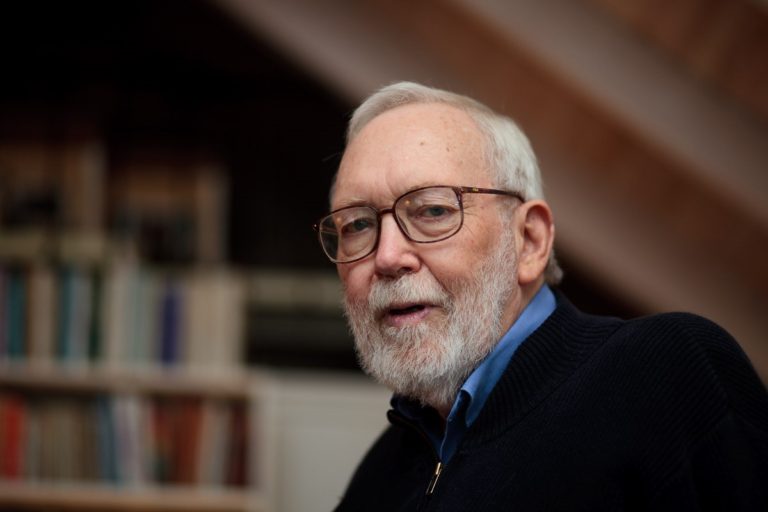

Like many of the animating figures of the historic avant-gardes, Lotringer’s life was blown off course by war. Born to Jewish immigrants from Poland in Paris in 1938, he was kept hidden in the countryside during the occupation. After, he lived with his family in Israel, before returning to Paris in 1958 where he was active in the Zionist socialist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair. To avoid conscription in France’s war against Algerian liberation he enrolled in the École pratique des hautes études. He wrote a doctoral dissertation on Virginia Woolf under the direction of Lucien Goldmann and Roland Barthes.

Lotringer’s intellectual formation owes something not only to his teachers but also to movement work as a left-wing militant in postwar France. The everyday life of meetings, groups, manifestos, of publications aimed beyond the seminar room. For ten years he wrote interviews and articles – mostly on English modernist writers – for Les Lettres Françaises, edited by Louis Aragon, the former surrealist turned communist cultural commissar. Lotringer was never in the party but breathed the air of its extensive cultural milieu. One way of thinking about his life’s work is that he took the praxis of a militant cultural worker and turned it into an art form.

After bouncing around in Turkey, Australia, and Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, Lotringer landed at Columbia University in 1972, where he would teach for more than 30 years. With a handful of others, he started Semiotext(e) as a journal in 1974. The filmmaker Jack Smith thought Hatred of Capitalism would have been a better title. That is what the 2001 anthology was called.

The journal had several landmark issues, notably: Schizo-Culture (1978), Autonomia (1980), Polysexuality (1981) and The German Issue (1982). These featured a mix of theory and literature juxtaposed against arresting visual imagery and art. In 1983, Semiotext(e) launched its famous Foreign Agents book series, with Jean Baudrillard’s Simulations. These small black books, with no preface or blurbs, were central to creating the 1980s passion in the Anglophone world for theory.

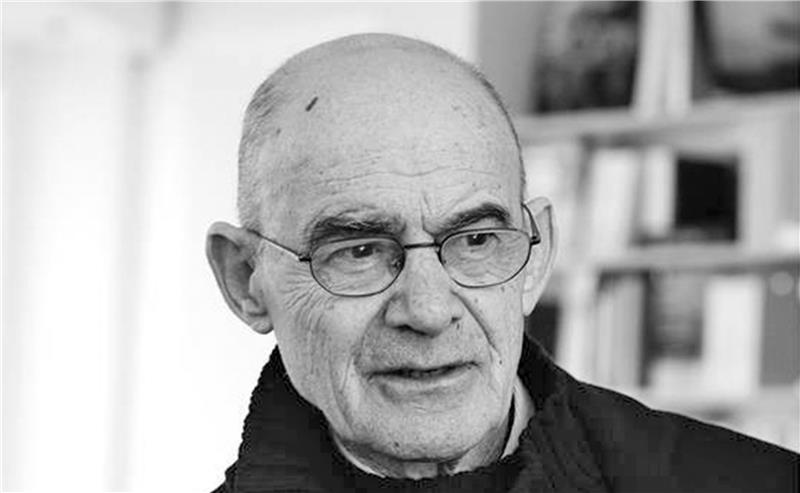

Once, when he lamented to me how little he had written, I remarked that he had not written much writing but he had authored several authors. Jean Baudrillard, Paul Virilio and Félix Guattari came to exist as figures in American letters in large part through his efforts. Their reception via Semiotext(e) took a different path to the passage of French philosophy into the High Theory practiced in elite humanities institutions. In Lotringer’s hands, it became low theory, the lingua franca of creative workers, avant-garde artists, and downtown bohemians.

Columbia professor by day, Lotringer was also a figure of nightlife, which is where many of us first encountered his warmth and generosity, his curious yet detached, inscrutable engagement. He was not exactly of the East Village scene. He was usually slightly displaced from it. That too was something of a method, a psychogeographic technique of understanding an ambience of the city from its edges. He was, among other things, a nightlife ethnographer, comfortable among those doing their best to refuse work and daylight but not of them. What was contemporary and original in Semiotext(e) came in part from this double practice of learning from the seminar and the soirée, the enlightened and benighted.

Through day and night, work and play, Lotringer came to see a connection between the way New York artists and Parisian philosophers responded to the failure of the festival of liberation in the late sixties, the global crises of the seventies and the rightward turn of the early eighties. In both milieux he found turns toward the materiality of language, experimental practices in social forms, engagement with media as a deepening presence in everyday life, and a refusal of the politics of representatives and representations.

The 1978 Schizo-Culture issue of the journal came out of a conference of the same name that Lotringer organized with John Rajchman in 1975. It brought together William Burroughs, Kathy Acker and John Cage with Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari and Jean-François Lyotard. The poster for the event was emblazoned with quotes from Deleuze about desire and Foucault on power, which signalled the will to go beyond the Freudo-Marxist dispensations then a commonplace among the New Left.

The Polysexuality issue pushed further into ways of thinking the possibilities of sexual practices as neither utopian nor pathological. Famously, it was typeset in all capitals to slow the reader down, as he, she or they perused the material gathered between the front cover image of a man in erotic congress with his motorcycle and the back cover crime scene photo.

At a time when the Italian Communist Party exercised a certain fascination among left wing intellectuals elsewhere, Autonomia looked beyond it to the Italian far left. It introduced many Anglophone readers to the political and intellectual energies of Mario Tronti, Antonio Negri, Paolo Virno and Franco Berardi. The German Issue likewise looked beyond the increasingly bourgeois-liberal world of postwar critical theory to the margins where the liberal-social democratic pact had little to offer. It put Alexander Kluge next to Ulrike Meinhof. Lotringer extracted both issues at least in part through the kind of street and salon ethnography that yielded his insights into the connections between theory and the avant-gardes in New York.

Meanwhile, the Foreign Agents book series continued to offer intellectual provocations in bite-size chunks. Lotringer was a superb interviewer and made several interview-based books, including Pure War with Paul Virilio, Hannibal Lecter, My Father with Kathy Acker and Germania with Heiner Müller. All remain excellent introductions not just to the signature concepts of these writers but also to their singular intellectual practices.

While it came out in the book series, Still Black, Still Strong (1993) functioned a bit like one of the issues of the journal, although here Lotringer and his collaborators worked as editors in the service of documenting the theory and practice of the Black Panthers. The book includes contributions by Dhoruba Bin Wahad, Assata Shakur and Mumia Abu-Jamal.

In 1990, Lotringer’s partner and collaborator Chris Kraus proposed a second book series as a counterpoint and corrective to the Foreign Agents. Christened Native Agents, these books challenged the apparent universality of the speaking position in what had become by now the genre of theory. The books both anticipated and contributed to the turn towards situated knowledges, in which the author is no longer the universal enunciator of universal difference. The series includes authors such as Eileen Myles, Bob Flanagan, David Wojnarowicz and Situationist International co-founder Michèle Bernstein.

In 2001, Semiotext(e) moved its base of operations from New York to Los Angeles – tracking with the rise of alternate cultural energy there – and switched distributors from Autonomedia to MIT Press. Hedi El Kholti joined as managing editor. Without detracting from the energy and direction that Kraus and El Kholti have brought to Semiotext(e), it is a tribute to Lotringer that Semiotext(e) has been able to grow and adapt and incorporate them. It is now among other things a major publisher of New Narrative authors, including Dodie Bellamy, Kevin Killian and Robert Glück. They came out of a San Francisco scene where mostly gay and lesbian writers grappled with the limits of the novel as form for non-heterosexual, non-bourgeois lives, and with the impact of theory’s decenterings of subjectivity.

Lotringer’s own writing is sometimes overlooked. Despite the singularity of his project, it always involved collaborators, and some of his best writing is his dialogs with other writers. The big book never quite materialized, but fragments of that project exist, such as Mad Like Artaud (2015). That book extends Lotringer’s dialogic practice to the past, presenting Antonin Artaud’s madness as a kind of shared affect with all of those around him and after him, including Lotringer himself.

What I remember from nighttime conversations with Lotringer is that the larger project on which he was trying to work was a reading of Artaud, Simone Weil, Georges Bataille as anticipators of that fascism and commodification that would sweep across all of their lives. He saw them as attempting to divert fascism’s primal energies into rituals of expiation, and failing at the task. Postwar history then appears as the wake of that failure.

One could think of Semiotext(e) as distracting him from writing more than an essay on this project (published as The Miserables). Or, as I prefer to see it, one can think of Semiotext(e) as that book. The press is a kind of meta-writing. It’s a book written through many others, updated and revised as it went along. How prescient it was that Lotringer worked his whole life against the embers of fascism of which commodification is not the liberal extinguisher but the accelerant. It’s a project that seems now even more timely than in the decades of Semiotext(e)’s formation when the figure to rail and rally against was neoliberalism rather than neofascism.

In Kraus’s novel Torpor, a Lotringer-like character’s refrain is: ‘it could be worse.’ It’s the mantra of a survivor. Lotringer was incapable of the optimism that animated much of the postwar left. Rather, he gathered and connected the energies that might avoid the worst. He certainly published and encouraged writers of a more utopian bent, but more out of a sense of their value as components in the struggle to avoid the worst.

Lotringer appears as a character in several other books: I Love Dick and Aliens and Anorexia by Kraus; Great Expectations and My Mother: Demonology by Kathy Acker; Inferno by Eileen Myles. There’s traces of him in more fictionalized form elsewhere as well. He was made to be a character in literature because he was one of those rare people who, for a good many people, drew together a storied era and made it both intelligible and deeply felt. He could have that effect on students, artists, but also people whose lives did not end up centering intellectual or creative labour but needed nevertheless to understand the play of power and desire that shaped the limits and possibilities of their lives.

As I remember it, Lotringer would express a sort of wry ambivalence about the success of the kind of theory he fashioned in the commercial art world. ‘It’s a living’, he might say, and flash that grin. When concepts or modes of writing lost their counter-intuitive force he was inclined to move on. There’s a certain ongoing variation and revision one can find playing out all through the Semiotext(e) list. It wasn’t meant to become, as Deleuze and Guattari might put it, sedentary. It wasn’t meant to have too consistent an identity. Or as Foucault once put it: leave it to the police to see that our papers are in order.

Lotringer taught us certain tactics. To conduct one’s life as a discreet yet visible site of experimentation. To look for the play of concepts between one’s pleasures and one’s struggles. To not settle into too dense a representation of oneself, one’s desires, one’s politics. To find languages adequate to the moment and to find the historical resonances of that moment, perhaps outside narrative arcs one merely inherited, from family, school or party. For those who work and play in certain discrete – and discreet – ways, he remains a model. A kind of genial, encouraging, present yet reserved theory-daddy, I name I call and recall him with love and more than a little irony, camp and otherwise.

Read on: John Willett, ‘Art and Revolution’, NLR 112.