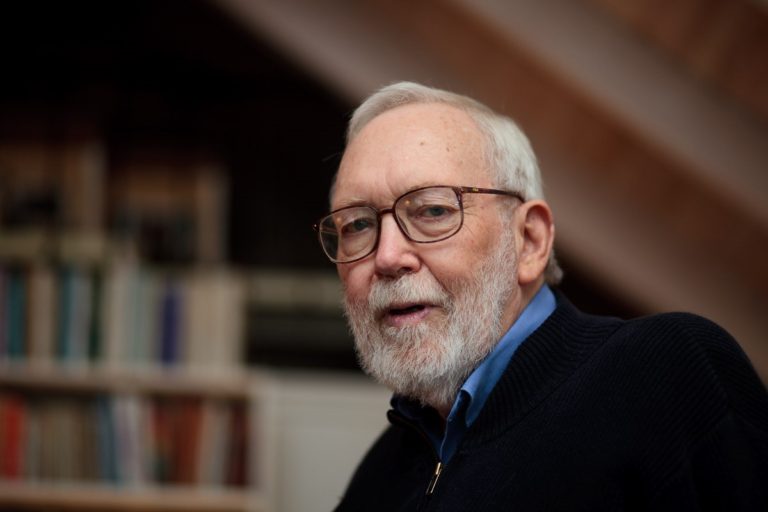

The death of J. Hillis Miller, in February, marked the end of an astonishing period in American academic literary criticism – North American really, since the dominant figure, Northrop Frye, was born in Québec and taught in Toronto. The period might be said to start in 1947, with the publication of Frye’s first book, the Blake study Fearful Symmetry, and yielded a body of work drawing on the kind of Continental resources – Marxism and psychoanalysis but also theology, linguistics, hermeneutics, and mythopoetics – that had been accorded little place by earlier formalist approaches. Miller, the author of twenty-five books, was rare among the central figures in devoting his attention to study of the novel, from Emily Brontë to Ian McEwan. The arc of Miller’s career has been described by Fredric Jameson as ‘unclassifiable’, but in bald terms, it was the story of a pair of Francophone mentors, Georges Poulet and Jacques Derrida, who washed up in Baltimore – more specifically, the campus of Johns Hopkins, where Miller taught from 1952 until 1972. Miller welcomed their interventions and ran with them, transforming himself into a leading exponent of two critical schools, one – phenomenology – that remains more or less pegged to its post-war moment, the other – deconstruction – with wider fame and implications, and a more contested legacy.

He was born in Virginia, in 1928, and raised in upstate New York – ‘definitely the boondocks’, he recalled. His mother was descended from Pennsylvania Dutch; one of her ancestors, a Rhode Islander, had been a signatory on the Declaration of Independence. Miller’s father, himself the son of a farmer, was a Baptist minister as well as a professor and an academic administrator who emphasised women’s higher education. But Miller’s upbringing wasn’t especially urbane. When he arrived at Oberlin, to study physics, he had never heard of T. S. Eliot. And when he moved to Harvard for graduate studies, he felt uncomfortable – out of step with what he called the ‘white-shoe tradition’. (Miller later wrote that he and his wife, Dorothy, thought of the shift from physics to English during his sophomore year ‘as a vow of poverty for us both’, adding, ‘That has not exactly happened’.)

The subject of Miller’s PhD was Dickens, not an established area of academic study. ‘The idea was that a gentleman had already read these novels’, he told me, during an encounter in 2012. ‘You don’t have to teach them’. When Miller was hired at Hopkins, he was the department’s first Victorianist: ‘Until I came, everything stopped at 1830’. One effect of the appointment was Miller’s meeting with the Swiss critic Georges Poulet, a member of the Geneva School of phenomenology (though, in fact, he never taught there), who argued that literature embodies the ‘consciousness’ of the author. Miller’s dissertation, notionally supervised by the Renaissance scholar Douglas Bush – whose only comment was that he uses ‘that’ when he means ‘which’ – had been written under the influence of Kenneth Burke, especially his idea of symbolic action. But in the published version, which appeared in 1958, he announced the Poulet-like desire to identify in Dickens’s fiction a unique and consistent ‘view of the world’ and called the novel the means by which a writer apprehends and creates himself.

Miller never formally rejected Poulet, but looking back, he saw his period as a phenomenologist as something like a diversion, even a cop-out. He had always been drawn to ‘local linguistic anomalies in literature’, he said, and consciousness criticism provided a ‘momentarily successful strategy for containing rhetorical disruptions of narrative logic’ through reference to the authorial perspective as a unifying – and grounding – presence. But at a certain point in the late 1960s, he abandoned what he called ‘an orientation toward language as the mere register of the complexities of consciousness’ in favour of ‘an orientation toward the figurative and rhetorical complexities of language itself as the generative source of consciousness’. In The Form of Victorian Fiction (1968), he continued to emphasise ‘intersubjectivity’ – how the ‘mind of an author’ is made ‘available to others’. But by the time of Thomas Hardy: Distance and Desire (1970), he had begun to embrace what he called ‘a science of tropes’.

It was a shift cemented in 1972, when Miller was hired by Yale, where his colleagues included Harold Bloom, Paul de Man, Geoffrey Hartman, and Jacques Derrida. Talk of a ‘Yale School’ now goes back almost fifty years, but did it really exist? Derrida, for his part, said that he didn’t identify with ‘any group or clique whatsoever, with any philosophical or literary school’. Yet Miller argued that in spite of such ‘complexities’ – i.e. the best-known putative member claiming otherwise – ‘a Yale School did exist’, and characterised its activities as ‘a group of friends teaching and writing in the same place at the same time, with closely related orientations’.

Miller once argued that the Yale critics were united by an interest in the eighteenth century. It’s a bizarre contention, the meta-critical equivalent of counting the people at a dinner table but forgetting to include yourself. Bloom, Hartman, and de Man were certainly engaged in an effort, spearheaded by Frye, to overturn a prejudice against Romanticism enshrined by Eliot and disseminated by the New Critical textbook Understanding Poetry. The notable products included Hartman’s 1964 study of Wordsworth, the essays in de Man’s Blindness and Insight (1971), and Bloom’s books on Shelley and Blake as well as The Visionary Company (1961), his foolhardy reading of the entire English Romantic canon. Miller, by contrast, specialised in fiction of the Victorian and modernist periods; as late as 2012, he had never read anything by Samuel Richardson.

So the orientations to which Miller alluded are not altogether clear. Even Deconstruction and Criticism (1979), the ‘manifesto’ of the Yale School, exposed the degree of ambiguity, the conjunction in the title separating Bloom from the ‘gang of four’ who practised something called ‘deconstruction’. Hartman complicated things further in his preface by calling Miller, Derrida, and de Man the true ‘boa-deconstructors’ – a gang of three. Even the book’s intended unifying element, an emphasis on Shelley’s ‘The Triumph of Life’, was lost along the way. Looser points of convergence seem more persuasive. Miller pointed out that what he, de Man, Bloom, and Hartman – a different gang of four – were up to differed substantially from the activities of both the New Critics and Northrop Frye. The late Irish academic Denis Donoghue said that what linked the members of the so-called Yale School was simply that they ‘teach at Yale’.

What remains beyond doubt is that Miller was closely aligned to de Man and Derrida, and that their influence explains the discrepancy between the best books of his early period, The Disappearance of God (1963) and Poets of Reality (1965), and the books he published while at Yale, Fiction and Repetition (1982), and The Linguistic Moment (1985), his book on poetry. Miller first encountered de Man’s work at a Yale colloquium in 1964 where he delivered a version of the paper that became the Lukács essay in Blindness and Insight. Another turning point was Derrida’s appearance, two years later, at the star-studded Johns Hopkins conference, ‘The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man’ – theory’s equivalent of the Sex Pistols concert at the Manchester Free Trade Hall. Miller was teaching a class when Derrida, a thirty-six-year-old lecturer at the École Normale Supérieure, and a last-minute addition – delivered his exhilarating lecture, ‘Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences’. But he witnessed Derrida in other sessions – for example, he heard him tell the phenomenologist and autofiction pioneer, Serge Doubrovsky, that he didn’t believe in perception.

It was one of many things he didn’t believe in. Derrida’s project, owing debts of varying sizes to Plato, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Freud, was to show that the majority of modern thought remained implicitly metaphysical, and posited a foundation – a Transcendental Signified, the logos or Word – from which many unchecked assumptions derived. The conference had been organised to remedy East Coast indifference to structuralism. In the event – a word that became a crucial part of theoretical vocabulary – the opposite was achieved. Derrida dethroned Claude Lévi-Strauss, and deconstruction was born.

You might say that the effect of deconstruction, in its literary-critical mode, was to augment a presiding canon of largely B-writers (Baudelaire, Benjamin, Borges, Blanchot, etc) with a group of H-figures (Hölderlin, Hegel, Heidegger, Hopkins, to some degree Hawthorne and Hardy), and to replace a set of keywords beginning ‘s’ – structure, sign, signifier, signified, semiotics, the Symbolic, syntagm, Saussure – with a vocabulary based around the letter ‘d’: decentring, displacement, dislocation, discontinuity, dedoublement, dissemination, difference and deferral (Derrida’s coinage ‘différance’ being intended to encompass both). And there was also a growing role for ‘r’: Rousseau, rhetoric, Romanticism (one of de Man’s books was The Rhetoric of Romanticism), Rilke, and above all reading, a word that appeared, as noun and participle, in titles of books by de Man, Hartman, and most prominently Miller: The Ethics of Reading, Reading Narrative, Reading for Our Time, Reading Conrad.

The New York Times, one of various media outlets that offered a beginner’s guide to this new creed, defined deconstruction as the theory that words and texts have meaning only in relation to other words and texts. That better describes the structuralist concept of intertextuality. A typical deconstructionist reading reveals the ways in which a text deconstructs itself, essentially by keeping irreconcilable ideas in suspension. (Caution: paraphrase ahead!) De Man argued, for example, that Hegel’s Aesthetics was dedicated to the same act – preserving classical art – that it reveals as impossible; autobiography at once veils and defaces the autobiographer; a literary text is something that asserts and denies its own rhetorical authority. Harold Bloom, in the recent posthumous book Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles, called de Man’s Shelley an ironist who believed that disfiguration annihilates meaning, and then pointed out that this also describes de Man’s Rousseau, his Wordsworth, his Proust…

If Derrida was the founder of deconstruction, and de Man its most concise and feline practitioner, Miller was responsible for extending its range beyond philosophy and poetry. He defined the novel as ‘a chain of displacements’ – author into narrator, narrator into characters, donnée into fiction. He pointed out that attempts to characterise the literature of a given period as closed or open are undermined by the impossibility of demonstrating whether any one narrative is closed or open in the first place. It’s possible to reply that Miller’s criticism gravitated to novels openly concerned with the challenge of reading signs, with language as something that both uncovers and evades: The Wings of the Dove, Lord Jim, Between the Acts. But in his essay ‘Narrative and History’, he argued that Middlemarch, traditionally considered a realist text, can be seen as displacing ‘the metaphysical notions of history, storytelling, and the individual, and the concepts of origin, end and continuity’ with ‘repetition, difference, discontinuity, openness and the free and contradictory struggle of individual human energies’. The ‘canny reader’s motto’, from his formidable – and longest-gestating – book, Ariadne’s Thread (1992), begins: ‘Watch out when you think you’ve “got it”’.

Miller also emerged as the critic best-placed, or anyway keenest, to stand up for deconstruction – against the right, who saw it as iconoclastic and jargon-riddled, and the left, who saw it as elitist. He was frequently forced to deny that deconstruction was simply nihilist. ‘It’s not that nothing is referential’, he said, ‘but that it’s problematically referential’. His best-known essay, and the most virtuoso display of his thinking in action, ‘The Critic as Host’, which appeared in Deconstruction and Criticism, was a response to M.H. Abrams’s essay, ‘The Deconstructive Angel’, which argued that a deconstructionist reading was parasitic on the ‘univocal’ reading of a text. Then there was the charge, recently repeated by Louis Menand in his book The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, that deconstruction was just as cloistered as the New Criticism – that it ignored, in Menand’s phrase, the ‘real-life aspects of literature’. There’s an argument that deconstruction only looked at history when history more or less forced itself onto the agenda when it emerged, in 1987, that de Man had published articles for Belgian newspapers under Nazi control. But Miller had already been engaged in rejecting the view of deconstruction as formalism by another – fancier – name.

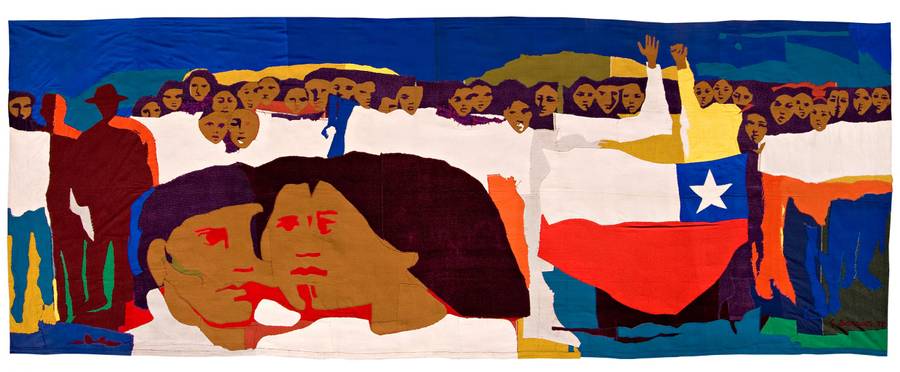

In 1986, the year he left Yale for the University of California, Irvine – Derrida went along too – Miller used his first Presidential Address to the MLA Conference to attack the narrowness of newly resurgent historical approaches, and his own later work offered a serial deconstructionist’s riposte. His first formal intervention was Hawthorne & History: Defacing It (1991), an attempt to show that literature never merely ‘reflects’ history, and this was followed by a short book on the relationship between text and images, Illustration (1992), which Jameson called his contribution to ‘“cultural studies” as such’. In the last decade of his life, he produced a study of George Eliot that doubled as an exercise in ‘anachronistic reading’, an account of writing – including the work of Kafka and Toni Morrison – in relation to Auschwitz, and a study of ‘communities’ (always more conflicted than they just appear) in the work of writers as varied as Thomas Pynchon and Raymond Williams.

But Miller was not content to offer deconstruction as an alternative to what he considered ‘logical’ historicism. He saw it as a truly materialist aesthetics. As long ago as 1972, Jameson argued that opposition to an ‘Absolute Signified’ encoded a critique of the authoritarian and theocentric, and compared the Derridean analysis of the word and its dominance to Marx on money and the commodity. The first overt statement of this position came a decade later in de Man’s essay ‘The Resistance to Theory’, in which he argued that those who dismissed theory as oblivious to social and historical reality exhibited an unconscious fear that it would expose their own ideological mystifications. Then he added, ‘They are, in short, very poor readers of Marx’s German Ideology.’

It wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to say that this one sentence determined the course of Miller’s work ever after. He became increasingly insistent on the similarity, even interchangeability, of the two traditions. Rhetorical reading was political reading, with an essential role in teaching citizens how to decode what he called the ‘imaginary formulations of their real relations to the material, social, gender, and class conditions of their existence’. In the 1986 MLA address, Miller called for a deconstructionist understanding of the material base. Later, though, he appeared to suggest that such an understanding had always existed. In ‘Promises, Promises’, a 2001 essay principally concerned with similarities between Marx and de Man, though inevitably emboldened by Derrida’s Specters of Marx (1993), Miller called The German Ideology ‘a deconstructive literary theory avant la lettre’, adding ‘If Marx is a deconstructionist, deconstruction is a form of Marxism’. Both were based, in his account, on a refusal to take things for granted, and a need to investigate how a certain sign system – language, the commodity – was established, how it works, and how it might therefore be changed.

There seems little consensus about the influence or afterlife of the movement to which Miller belonged. For many, it appears to have been something transient. Menand, in The Free World, argues that Derrida’s ‘anti-foundationalism’ never had much effect outside literature departments and ‘some kinds of art practice’. But Camille Paglia, writing in 1993, lamented that post-structuralism had ‘spread throughout academe and the arts’ and was ‘blighting the most promising minds of the next generation’, adding with only a dash of melodrama: ‘This is a major crisis if there ever was one, and every sensible person must help bring it to an end’. And Jameson, writing in NLR in 1995, noted that the ‘maddening gadfly stings’ of Derrida’s attack on metaphysics had hardened into orthodoxy – though he didn’t specify where.

Miller, for his part, liked to emphasise the deconstructive strain in the work of feminist critics such as Shoshana Felman, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Barbara Johnson (who pointed out that the Yale School was always a Male School), and Judith Butler. He never stopped writing and lecturing about Derrida or de Man or the self-immolating tendencies of language or the self-critical faculties of novels or the radicalism inherent in good reading. But he noted with regret that what he called ‘the triumph of theory’ had been undone, and he stopped using the term deconstruction, arguing that ‘a false understanding’ had won the day with the media, and ‘many academics too’.

Leo Robson is lead fiction reviewer for the New Statesman.

Read on: Fredric Jameson, ‘Marx’s Purloined Letter’, NLR I/209.