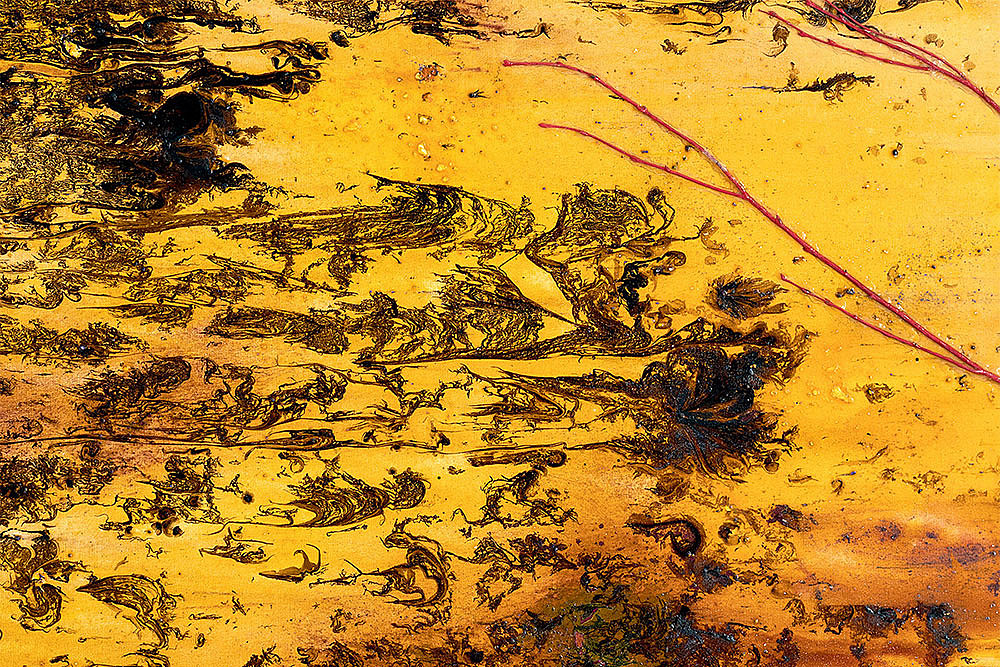

The American language, like the American landscape, is a trash heap. On top of the hundreds of thousands of loan words from over three hundred languages handed down from its British forebear, American English is strewn with the numerous subcultural slangs and professional jargons of a diverse, technocratically administered society, as well as the acronyms and neologisms born to designate two industrial revolutions’ worth of concepts, companies and consumer products (the most phonetically bizarre are undoubtedly those coined by the brand consultants in today’s tech and pharmaceutical sectors). From Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855) to Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems (1964), Adrienne Rich’s Diving into the Wreck (1973) and A.R. Ammons’ Garbage (1993), the sheer ontological profusion of a nation born and raised in capitalist modernity has fascinated its poets, many of whom have taken up the task of sifting through this detritus in their work, navigating the strange coagulations and dialectical reversals of ‘the natural’ and ‘the artificial’ that have ensued from the often violent, sometimes salutary contact between the cultures and economies of Europe and the dimensions of North American space.

Today, the American tradition of the literary gleaner is upheld by the poet, critic and visual artist Wayne Koestenbaum. Following in the footsteps of the New York School of poets and French transgressive writing, Kostenbaum, in his poetry and his critical prose, turns waste into a matter not just of aesthetic, but also ethical and political import. Like his father before him – a Berlin Jew who fled the Nazis as a youth, first for Caracas, then for northern California – Koestenbaum is a living representative of a lost culture: the gay scene that flourished in downtown Manhattan between the mid-60s and the late-80s, which produced a hyper-sophisticated connoisseurship for experiments in literature, dance, music and the visual arts before being decimated by AIDS. Koestenbaum left his home in suburban San Jose to go east for school, arriving in New York as a Princeton doctoral student in 1984, coming of age against the darkening horizon of the scene’s sunset years. The ensuing decades saw the razed terrain of downtown bohemia salted by conservative mayors, finance capital and real estate developers, who turned it into a space as culturally square as it is expensive. Now 65, Koestenbaum teaches Comparative Literature at the CUNY Graduate Center and lives in his old apartment on West 23rd Street, on the same block as the luxury condominium that was once the Chelsea Hotel.

Stubble Archipelago, Koestenbaum’s new collection, discards the short, Creeleyesque stanzas of his 1200-page Trance Trilogy (The Pink Trance Notebooks, Camp Marmalade, Ultramarine) with their full-stop-free, left-justified lines, visually cordoned off from each other by horizontal bars floating in the stanza breaks, for ones that retain the norms of punctuation, but vary long lines with short, indented lines and has more frequent recourse to enjambment. (In an elegant variation on the sonnet, each poem has a total of fourteen of these longer lines, spread across four stanzas.) Along with the clipped, implied-subject sentences that appear to owe their provenance to the notebooks Koestenbaum has kept for four decades – in the solitude of a diary one can begin with the verb rather than the first-person pronoun – the poems of Stubble Archipelago have the taut, angular dynamism of a vehicle making hairpin turns at speed, rather than the stop-and-go-traffic-tempo of the earlier collections. Not surprisingly, they provide the scene for fascinating collisions between contemporary linguistic ephemera (‘STEM’, ‘bromace’, ‘community standards’, ‘mansplaining’, ‘sub bottom’), high theoretical jargon (‘Anthropocene’, ‘subject position’, ‘heterotopia’), and scraps of French, Italian and German. These are fused together under the heat of witty changes in parts of speech – such as the verbifications of the proper nouns in the line ‘Thousand sex partners giggle to Sontag it / Mercutio her’ – and outré personifications – as when Koestenbaum ‘woofed the zeitgeist’ but ‘Temps perdu didn’t woof back’. This is ‘diction as drag, diction as ecstasy-catalyst, diction / as hairpin, dic- / tion as transitional object’, whose irreverent juxtapositions of tonal register, speaking of Sontag, are one of the hallmarks of camp sensibility in literature.

The overall effect is reminiscent of O’Hara’s ‘I do this, I do that’ poems, where ‘this’ is often ‘cruising’, and ‘that’ is often ‘dreaming’. The thirty-six lyrics form a complex spiral of conceptual oppositions between erotic mobility and oneiric immobility, flow and friction, fantasy and materiality, announced in the striated and smooth textures of Koestenbaum’s cheeky title. ‘Desirability’, as he observes in www.mypornessay.com, ‘rearranges space’. Thus the ‘ferocious stubble’ of a passerby ‘undoes wan / pedestrian’s equanimity’ as does the ‘flat-assed beanie-and-wedding- / ring wearing man reading / Financial Times on C train’, who alas is ‘fruitlessly cruised’. Koestenbaum conceives of space – whether it is the physical space of downtown Manhattan or the virtual spaces of the unconscious mind, social media apps, or the page – as a kind of Platonic khora, a murky atmosphere or surreptitious aura he sometimes calls ‘nuance’ and other times ‘fag limbo’, the latter being a zone where ‘all territorial claims, all hygienes between philosophy and poetry’ are thrown into question. Apropos Hart Crane: ‘the point of queer poetry’ is to ‘make murky, to distort’ the reader’s experience through unusual syntactical choices and stylistic mannerisms. Elsewhere, in an essay on his friend, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, he expands the definition of queer-affirmative writing to include ‘any . . . project buoyed by excess’.

Excess, as Koestenbaum employs it, is a synonym of waste, a conceptual filiation which owes a great deal to the theory of expenditure advanced by Georges Bataille in such texts as ‘The Solar Anus’ and The Accursed Share. Bataille rejected the Malthusian assumption of resource scarcity that underpinned classical economic theory in favour of what he called économie générale; far from being subsistence economies, pre-capitalist societies in Europe and elsewhere were based on the assumption of abundance, symbolized in the unlimited thermodynamic productivity of the sun. These societies were organized not around utility and cost-benefit analysis, but around displays of luxury, which took the form of useless expenditures of wealth, that is, around the deliberate waste of surplus production in highly aestheticized rituals of gift-giving and sacrifice.

For Koestenbaum, waste has a somewhat more ambivalent significance, depending on what kind of entity is producing it. On the one hand, there is the equation of ‘Garbage / fecundity’ and ‘ecocide’, which proceeds not only from ‘Anthropocene / bad vibes’ and ‘capitalism’s thrum’ but also waste’s ‘embeddedness within linguistic inattentiveness’ of a rotting ‘cultural system’ that forbids ‘slow discernment’ in order to produce apps, etch-a-sketches, Benadryl, craft beer, Stevia, chewing gum, shower curtains, GI Joe denim and the other assorted junk that is sifted through in Stubble Archipelago. On the other hand, the excreta produced by the body – urine, shit, pre-cum, tears, sweat – as well as its unruly overgrowths – Whitmanesque armpit hair, ‘memento mori pubes’, ‘hennaed Frühlingsnacht hospice hair’, hairy shoulders, eyebrows, mustaches, and of course, stubble – are lovingly attended to, along with their atmospheric odours. (In a medium that has historically prioritized auditory and visual effects, Koestenbaum does not neglect olfactory and tactile sensory experiences.) Although writing – an at-present overproduced and undervalued consumer good – might seem to fall into the former category of waste, Koestenbaum reclaims it for the latter. Because interpretation focuses on signification, it tends to treat the concepts that result as immaterial, and thus we often forget that language is something that is produced and consumed by bodies. Sex and digestion provide more apt metaphors for communication than any vocabulary that relies on mental states: ‘writing / is a waste product / and therefore disgusts us, / and we choose, / as ethical and lunatic / stance, to form literature in waste’s image’. To what end, this ethical and lunatic stance? Koestenbaum’s answer: ‘to stretch threshold / experiences’.

‘We have grown poor in threshold experiences’, Bataille’s friend Walter Benjamin noted in the Konvolut on gambling and prostitution in The Arcades Project, referring to those moments of transition between states of being pre-capitalist societies marked with ceremonial rites. Koestenbaum uses this as the epigraph for his essay ‘Heidegger’s Mistress’, and Benjamin’s ghost – along with the ghosts of Brecht and Adorno – haunts Stubble Archipelago. Watching a film set in Berlin, for example, Koestenbaum imagines the ‘rickety red house facades / my father or Walter / Benjamin might once / have passed’; he discovers ‘messianic time’s momentary / emissary’ – a reference to Benjamin’s theses on the philosophy of history – in the ‘meat’ of a men’s room tryst. Thanks to the disenchantment and rationalization of everyday life in market societies, one of the few threshold experiences that remains to capitalist subjects, according to Benjamin, is dreaming. Less than a century later, even that, as Jonathan Crary argues in 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, is under threat from developments in digital media, targeted advertising and the other insomniac technologies designed to ceaselessly extract profit from our attention, draining and impoverishing it. That is no doubt why such counter-strategies as unprofitable indolence and aimless wandering receive praise in Koestenbaum’s criticism, and why dreams appear so frequently in the Trance Trilogy and Stubble Archipelago. The twenty-nine dreams recorded in the latter – whose subjects range from visions of a ‘bombed, burning’ New York City to a performance of Montemezzi by his beloved soprano Anna Moffo – each constitute a small refutation of Henry James’s chestnut, ‘tell a dream, lose a reader’. No less than writing, dreams are the waste products of consciousness; to cross the threshold between waking and sleep is to enter a hazy land of excess experience; the experience of reading, whatever its subject, has much in common with hallucinatory and hypnogogic states.

Poetry has a distinctive formal tool at its disposal for simulating and stimulating threshold experience. Originally a layout convention for transcribing the metrical units of oral poetry onto parchment by scribes and later paper by typesetters, the line break is a visual demarcation of a boundary. Enjambment – from the French enjamber, ‘to stride over’ – is poetry’s means of allowing a reader to cross, after a momentary pause, the visual and sonic threshold of the line as she follows the semantic trail of the sentence; the commas, semi-colons, em-dashes, or ellipses that conclude lines are, on this analogy, not merely ways of organizing sentences, but are also like the stone horoi that were used as boundary markers in ancient Greece. For Koestenbaum, who describes his own poetic style in Whitmanian terms, as a ‘recklessly utopian vers libre approximating thought’s freedom’ and as a ‘democracy . . . of solitudes assembled in taboo congregation’, the ‘line-making impulse’ is a kind of ‘art activism’ and prefigurative politics, ‘a communitarian enthroning’ of a ‘heaven’ that can be ‘occupied today’, instead of deferred to the just political and economic order that may or may not lie in the future. And heaven, not unlike the dreams which are said to anticipate it, is a space of excess or surplus being usually only thought to lie beyond the ‘death-life interstice’, the ultimate threshold. If ‘fag limbo’ is a threshold space where the genres of poetry and philosophy meet, it is thanks to the ‘profound formalism’ of poetry’s ‘rear ends’ that it achieves philosophy’s stated goal: the preparation for death. Of Wordsworth’s sonnet ‘It is a Beauteous Evening, Calm and Free’, Koestenbaum writes: ‘he breaks the line because he wants to slay me, and I want to be slain: we participate together in this funerary rite’. It is a truth that holds for the writing and reading of all lineated verse, including his own.

This is no doubt why in his criticism – whether he is writing about Thoreau, Sontag, Schulyer or Bolaño – Koestenbaum takes such an interest in closural effects. (In By Night in Chile, for instance, he admires the way the ‘horror’ alluded to in the final sentence ‘remains offstage, as in a Greek tragedy’.) Stubble Archipelago concludes with a memory of himself as a fresh-cheeked, thirteen-year-old boy biking home, with his ‘Jacob’s- / ladder tail tongue hanging’ out of his mouth, open to a future where experiences will climb like angels into the heaven of what he characterizes in an essay on punctuation as his ‘suggestible’, ‘spellbindable’ brain. The image is an instance of the ‘stillness-in-motion’ Koestenbaum claims as the modernist ideal. It also recalls an observation he makes about Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel – another famous instance of the aestheticization of trash – in his commentary on Emily Dickinson’s poem ‘Called Back’. ‘Even a spiral or wheel consists of lines’, he writes. ‘The line’s odd secrets involve circularity, cycling and recycling, an ecology of perpetual replenishment, perpetual relineation’. For those who know the odd secrets of the line, as Koestenbaum does, thresholds – and threshold experiences – are everywhere.

Read on: Walter Benjamin, ‘By the Fireside’, NLR 96.