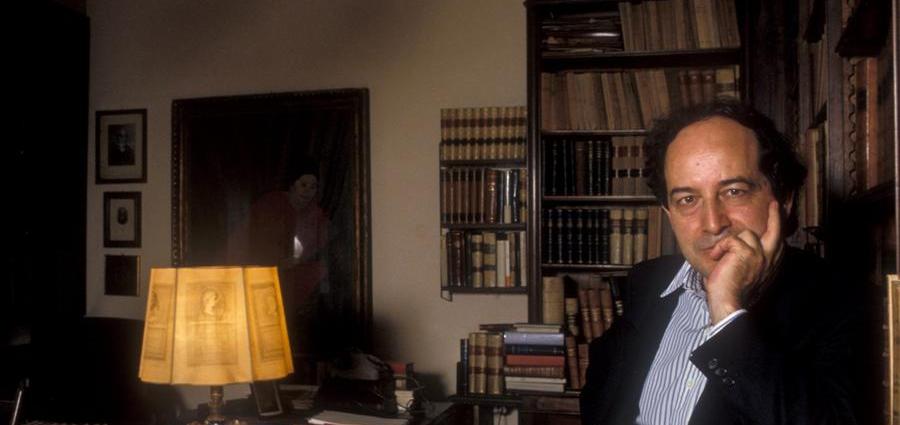

Roberto Calasso died this summer at the age of eighty. Among the unpindownable Italian erudites – Eco, Calvino, Pasolini – the author of the international bestseller The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony (1988), a hybrid meditation on the enduring relevance of Greek myth, is perhaps the hardest to figure out. The Marriage was the second chapter of a hazy, complex and confounding project – Calasso called it an ‘opera’ and would never explain much further – that might be described as a sustained effort to unlock the mystical potential of literature. Extending to eleven volumes with La tavoletta dei destini (2020), it ranges across world history and geography, freely connecting Kafka and Baudelaire, the Vedas and the Bible, Tiepolo and Talleyrand, Mesopotamian and Greek mythology. Of the first installment, The Ruin of Kasch (1983) – whose wandering, eclectically citational reflections on ancient ritual and the nature of the modern established his procedure – Calasso wrote that he wanted to steer clear of the essay form as it had become ‘sclerotized’. ‘From aphorism to brief poem, from cogent analysis of some specific issue to narrated scene’, the book he’d written was rather ‘a whole host of forms…’

Calasso’s hybrids gained worldwide traction in the cosmopolitan eighties and nineties, touted by stars of international letters like Brodsky and Rushdie – the latter praising the erudition and mix of novelistic and essayistic in his book on Vedic theology, Ka (1996). Not perceived as part of a cohort or scene (in contrast to Pasolini and Nuovi Argomenti, or Eco and the Gruppo 63), Calasso was never characterised as particularly Italian, and this always inhibited popular understanding of his work. Those who have frequented Italian bookstores in the last half century, however, have had a more intuitive path to Calasso. We have been able to read the books he worked on as a translator, curator, editor-in-chief, all the way to president and owner, for Adelphi Edizioni.

‘Bookstores were white back then’, long-time Adelphi editor Matteo Codignola told me about his teenage years. White was the colour of foremost left-wing Italian publisher Einaudi. They were ‘the canon of everything serious and beautiful. I loved Einaudi. And yet it’s not as if you saw their books and said “What’s that?” It might have been a study of Russian populism, on the enlightenment, interesting stuff – but you always knew what you were getting’. From 1962 however, bookstores also started carrying a collection of puzzling, colourful books: ‘It was hard to understand Adelphi at first. Going from Sartre’s Einaudi books to this stuff, it was a big leap… Adelphi’s books took us to unknown worlds.’

The house was founded by Bobi Bazlen, an intellectual with ties to Italo Svevo, Umberto Saba and Eugenio Montale, who died a few years later. Calasso, who joined in the midst of a doctorate on Thomas Browne, dedicated a short book to his mentor – oddly, wondrously, it came out in Italy the day after Calasso’s death. There he recalls Bazlen’s ‘ability to establish, as though it were obvious, the most acrobatic links: La via del pellegrino: you read that? If you like it, I think we should publish it along with Solitary Confinement by Christopher Burney, Father and Son by Edmund Gosse, and possibly a very different book as a fourth title, if god throws it our way’. The fourth volume might have been a history of Noh theatre. ‘The way they’d come one after the other had an exotic quality’, Codignola told me, that was ‘somewhat frowned upon’. In Bobi, Calasso writes that ‘For post-1945 Italy, the Irrational was everyone’s arch-enemy’, mostly in reaction to fascism’s bogus mythologies. ‘Bazlen, though, ignored those quarrels. He thought they were a waste of time’.

Adelphi’s books ‘felt dangerous’, Codignola said, ‘as everything literary was extremely targeted at the time: people wanted to know what you were reading and they judged you for it – you were right wing, you were less right wing, you were a comrade, a bourgeois…’ The relationship with the left-wing reader is crucial to defining Adelphi and Calasso’s impact on the Italian scene. Here’s how a major cultural player of the Italian left, Angelo Guglielmi, explained what the two meant to each other: Calasso is Adelphi’s ‘mirror image. Adelphi are very serious, find everything commonly known insufferable’, ‘they want nothing to do with any flatly pedagogical notion of publishing’, are committed to publishing ‘authors from cultures that are distant from the domestically humanistic tradition that rules Italy’. Calasso is just as ‘serious…he’s committed to what’s hard, and distrustful of what’s easy’, and deserves much credit for publishing those who have ‘made the Culture of the Modern’, showing Italian readers how Nietzsche let philosophy give in to the real pressure of the world, highlighting the ‘fragrance’ of Adorno’s prose in opposition to the ‘grimness of the new dialectics’, the value of the ‘enraged aesthete and euphoric moraliste’ Karl Kraus…

A big ‘but’ is coming from Guglielmi, but let’s hold it for a minute.

Let’s go back to those white books offering the canon from Marx to Beauvoir. Luciano Foà is said to have left Einaudi to join Bazlen because they refused to publish Nietzsche. To defend Adelphi from accusations of being right wing it was always necessary to explain that the orthodoxy in left-wing publishing was leaving out too much. Adelphi saw Einaudi’s approach as narrowly instrumental, committed to serving only practical needs. ‘The earth is crumbly… perspectives wobble’, Calasso writes in the The Unnamable Present (2017). The ‘unnameable present’, Elena Sbrojavacca, author of the only comprehensive study of his work, summarises, ‘is the progressive teleological skidding from religious to social, where every element of society is only invited to convey their efforts toward the interest of society itself and only that’. Calasso thought that literature was meant to serve a different god. What this god was is hard to tell, maybe the invisible itself, the hollowness we come from.

In his writing, Calasso strived to create a circulation between the visible and the invisible. That’s my favourite expression of his. Sbrojavacca writes that ‘on every page Calasso invites us to use reading as an instrument to investigate the unseen’. Literature, in this conception, is the polysemic, ambiguous vessel we can use to venture into the invisible. La Folie Baudelaire (2009) is perhaps most explicit on this. Calasso argues that the French poet is the master of analogy, and represents the moment where the sacred becomes the purview of literature as the rest of society abandoned it. Analogic thinking is presented as the only way to access the kind of knowledge ‘that shines a light on the natural obscurity of things’. This is why everything in Calasso is juxtaposed but never explained. The ‘opera’ was a gnostic project, shrouded, as most gnostic projects are, in a mist of poetry, eruditeness, and beauty.

As Baudelaire explained in a letter cited by Calasso, ‘the imagination is the most scientific of the faculties, because it is the only one to understand the universal analogy, or that which a mystical religion calls correspondence’. This aspect of Baudelaire is said to place him in a lineage of ‘pansophists’. ‘Universal analogy: it suffices to utter this formula to call up, like some vast submerged architecture, the esotericism of Europe starting from the early fifteenth century. The forms it assumed were numerous – from the mild Platonism of Ficino to Bruno’s harsh Egyptian version, from Fludd’s Mosaic-naturalistic theosophy to Böhme’s Teutonic-cosmic variety, down to Swedenborg and Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin’. This freewheeling argument ends with a quote from Goethe: ‘Every existent is an analogon of the entire existent; and so that which exists always appears to us isolated and interwoven at one and the same time. If one follows analogy too closely, everything coincides in the identical: if one avoids it, all is dispersed in the infinite.’

The words by Guglielmi quoted earlier come from a newspaper debate over Calasso’s The Forty-Nine Steps (1991), a collection of essays on his favourite European authors. Guglielmi argued that this canon – from Adorno to Heidegger, Kafka to Gottfried Benn – consisted of the ‘authors of end times’, for whom ‘modernity was not a step forward in history but its grinding to a halt’. ‘What Calasso lacks is the curiosity for the strivings of the present. Maybe the reason is he doesn’t believe there is a later to the earlier he is used to devoting his attention to, as he is convinced that that earlier is also the now’. Calasso though was busy doing something different, in the process rearranging the perception of writers in Einaudi’s backlist. Here’s his take on Walter Benjamin: he was ‘the utter opposite of a philosopher: a commentator. The boastful immodesty of the subject saying ‘I think this’ was fundamentally foreign to him. … his dream was to disappear, at the acme of his oeuvre, behind an insurmountable lava flow of quotes’ (this also works as a description of Calasso’s own books).

The harshness of Guglielmi’s judgement is testament to how strongly his side felt that this was all just unorthodox ricercatezza, something decadent and bourgeois by default: ‘The present times being missing from his work, you can only read him for erudition, or the pleasures of good prose’. Most Italian left-wing intellectuals today would be hard-pressed to choose a side, since we are the offspring of both. I think I know what Codignola meant when he told me about a time when everything seemed to make sense, but that Adelphi’s books made you feel that the others weren’t telling you the whole truth. I also feel that while the likes of Guglielmi saw themselves as different in kind to the generation spawned by the Miracolo Economico and portrayed in the Commedia all’Italiana, Calasso must have felt that this self-referential, booming society was too self-involved and lacking in transcendence; he must have had a unique view of the sleazy mix of Marxism and establishment, seaside villas and existentialism, of the characters played by Mastroianni in La Notte and La Dolce Vita.

Calasso didn’t really want to debate with his foes. In The Unnamable Present he wrote of the present time: ‘Thought would benefit more than ever from a period of concealment, of a covert and clandestine existence, from which to re-emerge in a situation that might resemble that of the Pre-Socratics. The powers have to be recognized before even naming them and venturing to theorize the world.’ Alfonso Berardinelli, one of Italy’s best critics, seemed to assent to Calasso’s argument even when highly critical: ‘Modern western literature begins its existence when Europe relinquishes traditional saperi and perennial philosophies. It’s not a given that renouncing all that was a good thing. The virtues of doubt and criticism have been exercised without limits for so long that now we don’t know what to think anymore, where to go, what to love’. Calasso, then, ‘is right on some level’ to devote himself to ‘the superior mind, ecstatic and enlightened’.

Berardinelli wrote this in 2007. The debates that faded with the end of the Italian Communist Party were by now a distant memory, and yet Calasso remained obsessed by his own ‘fight against the modern Western world, against the notions of History and Progress, against the Enlightenment and against “leftwing” politics…’ In Bobi, Calasso cherry-picks from his mentor’s writings, giving a sense of where his own focus was towards the end: ‘And when the revolution comes I’ll put my dinner jacket on and light a cigarette (Egyptian Prettiest Chinasi Bros.) read a Henry James and wait for the son of my portinaia to come take me to the guillotine; it’ll be great times I hope I’m not a coward…’ Sbrojavacca told me that Marx in fact was ‘one of the most important authors for Calasso. He says Marx is a demonologist as he can see the ghosts that haunt the modern world. His criticism of Marx, and of Freud, is that they are human types from the second half of the 19th century who tried to tame the wildness of the modern world, tried to find a way to act on the modern world… a way to cheat the machine and harness the ghosts and make them work the way they wanted to’.

And in Bobi, Calasso quotes this fantastic passage Bazlen wrote on Freud: ‘Hunched over his microscope, Freud discovers the soul’s bacilli. And so he discovers the soul. But he is a 19th-century scientist, and he believes that the soul’s riddle is only solved by looking at the bacilli. He’s a scientist, he refuses to be considered a philosopher, and yet, from his work, a work born in that environment, a philosophy implicitly is derived, a vision of life, a program, a human ideal: of the Man with the Pasteurized Soul, who, in a world that has lost all symbols, and in virtue of his finally normalized sexuality, has the libido liberated that is necessary to finally pursue a career.’

Both Einaudi and Adelphi’s partisans ultimately managed to do enough character assassination to give us a feeling that the fight amounted to nothing. And yet it is Calasso’s adversaries that shed the most light on the risks he took. In that same article, Berardinelli wrote: ‘Calasso (it seems to me) wants everything: to be a sorcerer and a dandy, a neo-ancient man of wisdom and a postmodern narrator (and antimodern). He wants it because he can have it: the neo-ancient is postmodern and today’s sorcerers, here, are just one specific kind of dandy. Since all mystical investigation has ended for the West a few centuries ago, it reappears as illustration, mise en scène, decoration, culturalist orgy, aestheticized depth’.

Codignola employed some Adelphian irony on the ‘decoration’ part. After the successes of Kundera and Calasso’s books, Adelphi ‘went from 10,000 to 50,0000 copies… In the meantime, the gnagnera started of how chic how refined how snob how elitist they are, which Roberto and I both disliked – well obviously you can spot some mannerisms here and there, but it wasn’t a plan… Then people start saying they loved our pastel-coloured covers, “so elegant!” Somebody wrote me once: “I need to furnish my house in Capalbio” – that’s where some of the more wealthy left traditionally goes in the summer holidays – “I need 30cm of pink 30cm of yellow, and 20cm of red if you can find them”… She meant the colour of spines and covers to arrange on the shelves, regardless of authors and titles… she sent me a blueprint of the house, and colour codes’.

If it became decoration for some, Adelphi was the darkroom of Gen X readers. When I was twenty, I told my mother I must kill her and my father in order to be free. I was brandishing my yellow, compact Nietzsche books, where I was supposedly learning about how thin the veneer of civility in my parents’ centre-left and Catholic world view was. A dear friend of mine appeared in a television show with Calasso a few years earlier, a lesson on Greek myth with an audience of high-school students. A handsome young erudite who listened to Blur and appeared destined for a centre-left Weltanschauung, he was tasked with asking Calasso a question: ‘What can we get from myth, today? Can it still show us the way to the spiritual life?’ Calasso replied that we can indeed try to use myth, to ‘try to enter that circulation and understand things we otherwise wouldn’t’. He says one crucial thing: that it’s up to the individual to choose it for themselves. By 1997, individual solutions to problems were now the norm for most of us.

My friend converted to Catholicism two years later and is now a vicar in the Netherlands. He pursued the circulation of visible and invisible.

Read on: Perry Anderson, ‘Lucio Magri’, NLR 72.