It was not easy finding the exhibition Sismographie des luttes at the Centre Pompidou. There were no posters to announce its presence outside or in the main hall. When I visited one Saturday morning recently, I even wondered if I’d made a terrible mistake, and the show was already over. Asking one attendant I was directed to the fifth floor but the staff up there at the turnstiles looked at me blankly when I mentioned it. So I wandered through the permanent collection and out into a long corridor where, at the end there was a window looking out across Paris and to the left, with no signage at all, a single room held the exhibition.

It was all a far cry from the previous outings this exhibition has had around the world: in Beirut, Cali, Dakar, Rabat, New York. What the Pompidou effort suggests is a discomfort, embarrassment even, at dealing with the subject of colonialism head-on. This is not something that Beaubourg has been known for engaging with since it opened in 1977.

Taken alone the exhibition reflects only a fraction of the extraordinary project it draws from. This began in 2015 under the direction of Zahia Rahmani, a writer and historian based at the Institut national d’histoire d’art in Paris. For several years she has led a small team of researchers dotted around the world who have been working to track down a thousand journals dating from the 19th Century up to 1989. The oldest on the list dates back to 1817 – the Haitian literary and political journal L’Abeille haytienne – and the subjects they cover range from politics and race to culture of all kinds. Every region is represented. The connecting thread between them is their existence within and in some way in opposition to a system of colonialism or oppression.

‘People are not passive, that’s what interested me’, Rahmani said when we met recently, describing her motivation for seeking out these journals. ‘We should give history another path than that which consists in thinking that everything emanates from the declaration of human rights.’

There are so many striking journals in the collection, and to see them revived in this way is moving and inspiring. Some existed for only a few issues, such as Zimbabwe’s Black and White that dealt with racial politics in 1966-67, while others such as the literary journal Sur from Buenos Aires – which treated social problems and was briefly banned under Peron – operated from 1931 until 1992. Others remain in circulation today. The geographical and topical range is remarkable. Indigenous populations from Australia to North America have their place, so too do an impressive selection of feminist publications from the Middle East and Asia, such as the striking Seito founded in Japan in 1911 which tackled homosexuality, drugs and abortion. To go through the list is to have so many new doors opened: one wants to walk through them all. There is the Turkish Šehbāl for example, active from 1909 to 1914, that covered music, philosophy and women’s rights and contained many stunning photographs and illustrations, or the satirical Phong Hóa whose pages were full of sharp-witted cartoons, appearing weekly out of Hanoi from 1932 until it was banned by the French authorities three years later.

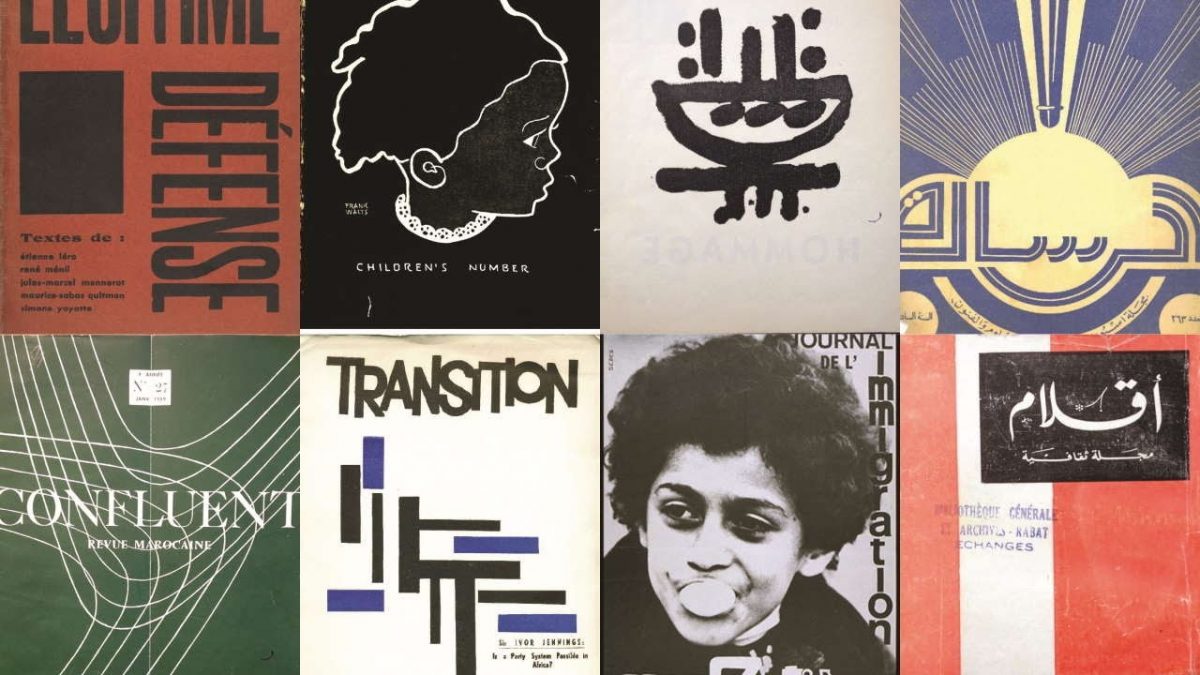

To better grasp the scope of the project, and delve further into it, one must turn to the two catalogues published by Nouvelles Editions Place, and above all the online portal SISMO, an invaluable resource that continues to expand as the team’s research goes on. Free to access, anyone can explore the entire list, which leads to full digitalised contents for some, and at the very least a dedicated page containing information on origin, lifespan, language and cover image – so often a gem of graphic design, such as the art nouveau illustrations of Althaqafat alisuria, a journal of Syrian culture from 1934, or the bold covers of Mozambique Revolution that ran from 1963 to 1975, throughout the war of independence from Portugal.

But the exhibition allows us to see the journals as material objects, complete with yellowing pages and dog-ears that evoke the many hands they once passed through. In the Pompidou’s room a few glass cases display editions of selected journals, highlighting the myriad formats used, from the broadsheet The Black Panther that the party put out, to a review such as Proa set up by Borges in 1922 that mixed sizes, with one issue on display around A5, another just under A2. Seeing all this gives a real and palpable quality to the radical contents of these journals: aesthetic objects that were also instruments of struggle. As Rahmani put it, all those involved in these journals over two centuries

participated in an aesthetic that is not violent. Of course there is violence in the sense that people are fighting, but they are struggling to be able to preserve a culture, or even their language, the possibility of living together, and of not living under coercion. They find release through the journal because it is not a weapon, it is a negotiation . . . and that’s what the installation showed me, that over two centuries there is a temptation to still nevertheless seduce the one who oppresses you, by reminding him who you are.

The contents of the exhibition has varied according to the location, with each space tending to showcase journals that relate to the local context and hold events to encourage people to delve into the issues they raised. None of this at Beaubourg. The selection here is both minimal and flat – the journals are presented as artefacts rather than alive and still the source of relevant debate. Also missing is a table with computers allowing visitors to explore the journals beyond those displayed in the room, something that was a feature at the other locations.

The centrepiece of the exhibition at the Pompidou and elsewhere is a film installation, which is made up of two sets of three still images projected against two walls showing around 450 journals and 900 documents. This runs on a loop to a soundtrack composed by Jean-Jacques Palix, a mixture of instrumental music with archive extracts from speeches made in defence of causes related to the journals. We see covers, inside pages, photographs of founding editors or other key figures. There is also a seventh image projected between the two sets of three with short paragraphs of text telling us about a particular journal, or related quotes. The semi-darkness of the Pompidou setting is another underwhelming choice on the part of the museum. Other venues provided the film installation with the cinematic setting it demands. At the Beirut Art Centre for example, the exhibition was held in such a dark space that it encouraged visitors to sit and watch the film all the way through. And indeed it is worth taking the time to experience the powerful, cumulative effect of viewing these hundreds of examples of printed resistance over more than a century, from all across the world.

The thousand journals are in around 70 different languages, including Creole variations, Mohawk, Tibetan, Zulu, Uyghur and Laotian, to cite only a few. But 222 of the journals are in French, 217 in English, and 199 in Spanish. This forces the question of intended audience – employing the language of the ruling power meant that many groups had no chance of reading the articles defending their cause. And it is here that the double function of the journals is evident: their memorial function for history, and their active function, ‘aimed at trying to develop within the colonial system a sensitivity towards them’, as Rahmani put it. ‘What is incredible is how these intellectuals manage this transition, they speak the language of empire, they master it, but they address empire in a critical fashion. It is very courageous’. Courageous is, indeed, the overriding impression one has when looking and exploring all these publications, now given a second life.

Read on: Emilie Bickerton, ‘Planet Malaquais’, NLR 84.