Film history is full of holes. Forget about the idea that ‘everything’ is available on the internet; everything isn’t available in the archives. The Deutsche Kinemathek estimates that eighty to ninety percent of silent films have been lost. Fire, censorship, neglect, the recycling of silver from the emulsion of nitrate stock: the reasons vary but the result is the same. Although the problem lessens dramatically beginning in the 1930s – a decade that saw the foundation of the world’s first film archives – it does not disappear. The farther away one gets from capital-intensive production, mainstream acclaim, or state-approved cultural patrimony, the more likely it is that a film will disappear or fall into material precarity, existing only as a bad VHS copy passed from hand to hand, and then as a worse digital file, uploaded and downloaded.

The reality of oblivion fuels fantasies of rediscovery. Rarely are these dreams as wholly fulfilled as in the case of About Some Meaningless Events (De quelques événements sans signification, 1974), directed, written, and edited by Mostafa Derkaoui. This debut feature, now streaming on MUBI, was shot in working-class areas of Casablanca by a group of young artists and intellectuals eager to ask what filmmaking could be in Morocco, a country where a national cinema had not yet truly been born. Their speculative, energetic answer was not to the liking of King Hassan II, a despot who was intent to clamp down on dissent and manage the national image following attempted coups d’état in 1971 and 1972. After a single screening in Paris in 1975, the regime suppressed the film and prohibited its export, consigning it to a clandestine existence. The ban was lifted in the 1990s, but when the Madrid lab holding the negative went bankrupt in 1999, the materials were seized as assets. They eventually wound up at the Filmoteca de Catalunya, where the film’s director and his brother, cinematographer Abdelkrim Derkaoui, supervised a stunning restoration. Now, nearly five decades after its first fleeting appearance, the film has finally entered widespread circulation, taking its rightful place as one of the great works of 1970s political modernism. Better late than never.

MUBI labels About Some Meaningless Events a documentary. Certainly, the film takes inspiration from the ethos of cinéma vérité, capturing life in a crowded neighbourhood bar and out in the street with a lightweight, sync-sound 16mm camera. Never do the filmmakers occupy a private interior; they remain at all times in public, subject to the vibrant reality that surrounds them. Like Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch, who in Chronicle of a Summer (Chronique d’un été, 1961) roam Paris, holding out a microphone to passers-by, asking if they are happy, Derkaoui’s crew seeks the vox populi. They conduct a series of interviews, posing questions that bear directly on the activity at hand: their topic is the cinema, and Moroccan cinema in particular.

According to Sandra Gayle Carter’s book What Moroccan Cinema?, at the time About Some Meaningless Events was made, the country had produced less than a dozen feature films. (Her volume’s ironic title telegraphs the enduringly fragile state of filmmaking in the nation.) Meanwhile, new waves were surging around the world and filmmakers from Buenos Aires to Havana to Oberhausen were composing manifestoes, setting out the way forward. It is against this double backdrop that Derkaoui, freshly home after completing a degree at the renowned Łódź Film School, hit the streets. Instead of proselytizing for a predetermined position, he canvases for opinion. What stories should a Moroccan national cinema tell? Should it aspire to the tremendous commercial popularity of the Egyptian cinema, or of karate films like The Big Boss (1971), starring Bruce Lee? Or should it follow the revolutionary example of Latin America and commit itself to formal radicalism and the project of cultural decolonization? Do Moroccans want to be entertained or to see the country’s social problems represented onscreen? The discussions are wide-ranging, broaching matters of genre, aesthetics, and audience. No consensus emerges, but one thing is certain: About Some Meaningless Events conforms to none of the examples mooted throughout its 78 minutes.

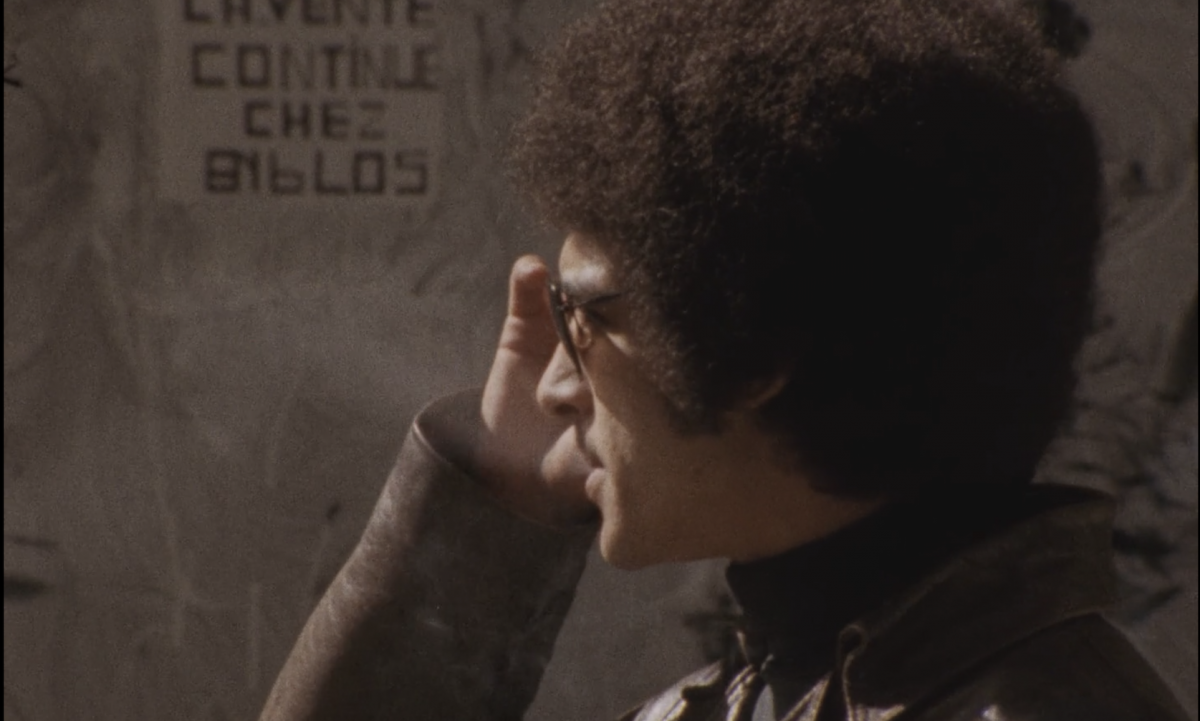

Crucially, the interviews are conducted not by Derkaoui himself, but by Abbas Fassi-Fihri, a journalist cast in the role of a director who is making a movie. Derkaoui orchestrates a mise-en-abyme: the inquiry on the future of Moroccan cinema is a film within a film, a documentary nestled within a fiction. The two layers are frequently indistinguishable, sharing a proclivity for handheld close-ups and a title – judging by the clapboard that appears onscreen, at least. When the production crew hangs out at the crowded bar, looking hip and flirting with women, it feels like a hundred stories are circulating through the smoky air, just out of reach. Every now and then a hint of one comes through in a line of dialogue without congealing into anything that lasts, as if the artifice of storytelling were trying and failing to break through the flow of life again and again. Why does one man wave around a crab and another, later, plop a fish in someone’s glass? What kind of appointment is the woman wearing the bright yellow faux fur coat in the midst of arranging? The bustle of the bar refuses to resolve into the tidiness of cause-and-effect narration, yet all of its unscripted vitality is the product of a staged conceit.

One plotline gradually does take root, rising above the collective din to tell the story of an individual. Early on, a young man appears alone on the street, smoking as he watches a bearded man get into a car and drive away. He hops on a scooter, possibly one that doesn’t belong to him, and departs, only to reappear in proximity to the filmmakers – suggesting that this character, whose name turns out to be Abdellatif, is more than just another member of the crowd. Later in the bar, he is there again, his gaze fastened on the same man from before, who now holds court at a table that reeks of corruption. When Abdellatif confronts the man and a brawl erupts, the direct sound usually present throughout the film disappears, leaving Włodzimierz Nahorny’s propulsive free jazz to fill the track, bursting with improvisational vim. Abdellatif fatally knifes the kingpin and the horns squeal. If the premeditated plotting did not make it evident already, the stabbing leaves no ambiguity as to the film’s fictional dimension. Little else can cleave documentation and fabulation like the difference between the obscenity of real death and the thrill of its dramatic contrivance.

The event transforms the nature of the film crew’s questioning. They turn away from the public and towards each other, gathering in the open air to debate how or if the stabbing should be incorporated into their film-in-progress. It transpires that the man was Abdellatif’s boss at the port. What motivated the violence? How does it relate to the broader context, to the exploitation of workers? What are the respective merits of fictionalizing the episode versus foregoing scripts and actors to shoot ‘sur le vif’? In a meandering and conflictual way, the conversation maps a series of issues leftist filmmakers were confronting internationally at the time: class privilege, the politics of form, and the ethics of packaging struggle and trauma for consumption. In what may well be a shot at Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969), one man complains, ‘Even the student protests have been recuperated by Hollywood!’.

The murder is a high-stakes eruption of contingency that demands narrativization, whether through the personal history of its perpetrator, the grind of social forces in which he is caught, or some combination of the two. It is the stuff conventional films are made of, an event pregnant with the promise of meaning. As About Some Meaningless Events winds to a close, the crew takes the bait, doubling down on their vérité methods in an effort to make sense of what happened. They interview Abdellatif’s colleague and ask a friend about his family background. Finally, they visit him in police custody. Abdellatif tells them some of what they want to know: the difficulty of finding good employment, the bribes his boss demanded, what life is like in a neighbourhood he is sure the interviewer knows nothing about. Ultimately, though, he becomes frustrated and turns the tables on the filmmakers, challenging their desire for knowledge and the importance they assign to the cinema: ‘And you think you’re changing something with your camera?’ Returning the gaze of the apparatus, he puts an end to the encounter – and to the film we are watching. A distrust of the ideological betrayals of fiction and a hope that a commitment to reality might mitigate them are palpable throughout About Some Meaningless Events. At the same time, Derkaoui never lets documentary off the hook either, making full use of the powers of the false to query any claims it might make to social transformation or political righteousness.

Writing in Cahiers du cinéma in 1969, Jean-Louis Comolli remarked that a certain kind of fiction film was beginning to look a lot like documentary. It wasn’t a matter of simply poaching a visual style associated with authenticity, as happens often today; these were works that left behind the script and the studio, gave up on big budgets and 35mm, and embraced an understanding of cinema and reality as reciprocally produced in the act of filming. It was here, and not in the idea of making contact with a pre-existing reality, Comolli argued, that the radicalism of ‘direct cinema’ resided. Whether occurring in films deemed fiction or those called documentary, these changed working methods released filmmaking from the stranglehold of the commercial system and its conventions, revealing their repressive character and opening new, counter-hegemonic possibilities of expression.

Comolli’s unorthodox revision of direct cinema as a concept untethered from the distinction between documentary and fiction, defined instead as a mode of production and a way of making meaning, sheds light on the reflexive gambit of About Some Meaningless Events. Against the repressive weight of Morocco’s Years of Lead, the film dwells in a wealth of microevents occurring in an everyday world lacking any centre of coherence, a world the film produces as much as reproduces. Certain of little, it traffics in an abundance that refuses the fixity of categories, troubling not just the line between documentary and fiction but, perhaps more importantly, the distinction between significance and insignificance. Rather than focus on a single (anti-)hero or an exemplary incident poised to neatly tie everything together, Derkaoui offers something else: a relentless self-questioning that takes place in and through a sea of faces captured in close-up after close-up, pushing in and out of a frame that rarely relinquishes its tight hold. The result of this insistent proximity to the hum of life is nothing like claustrophobia; it is a gorgeous parade of ungovernable particularity, a portrait of national heterogeneity and dissensus. Could it be an anti-authoritarian aesthetics? No wonder the king was so against it.

Read on: Emma Fajgenbaum on the ghostly realism of Pedro Costa.