Like the biologist’s dye that stains bodily tissue and illuminates its cellular structure, the laboratory-grade opportunism of Markus Söder is a useful resource for understanding German politics. As the Minister President of Bavaria and leader of the Christian Social Union, Söder currently polls as the leading contender to replace Angela Merkel as Chancellor next year, despite not having declared his candidacy. The calculus is not strained: the CDU’s own three pretenders – Norbert Röttgen, Armin Laschet, Friedrich Merz – could all cancel each other out. For all of northern Germany’s imputed reluctance to being ruled by a Bavarian, the closest election in postwar German history was between Söder’s political mentor, the Deutschmark fetishist CSU leader Edmund Stoiber, and Gerhard Schröder, who only narrowly won after he cannily channeled popular discontent about the US plan to invade Iraq. Most decisively, Söder is a Nürnberger from the relatively industrialized region of Franconia, not some primitive mountain yodeler of Berlin caricature.

From his earliest days, the German press identified Söder as a formidable political animal. After a minor deviation in childhood, when the five-year-old Söder brought home a ‘Vote for Willy’ sticker and his father enjoined him to pray for his sins, Söder slickly ascended the ranks of the Christian Social Union: president of the youth wing of the CSU at 28; CSU association leader for Nürnberg-West at 30; CSU media commissioner at 33; CSU general secretary at 36; CSU chairman for Nürnberg-Fürth-Schwabach at 41; Minister President of Bavaria at 52; and, as of last year, party chairman of the CSU at 53, with a standard CSU-majority of 87.4 percent of the party vote behind him. In what is essentially a Catholic political aristocracy – the CSU now has a room of its own in the Bavarian Historical Museum in Regensburg that follows the suites devoted to the reigns of Ludwig I and Ludwig II – Söder is perhaps only unusual in being a Protestant. Long known as the CSU’s attack dog – a reputation only aided by his beefy figure and faintly menacing, and quite possibly self-administered, haircut – Söder has been known to pick gratuitous fights with opponents. His ability to switch positions nimbly with plausible conviction, and his sheer enjoyment of political battle, has consistently earned him comparisons to Schröder. In their biography of the ‘Shadow Chancellor’, Roman Deininger and Uwe Ritzer note that Söder, who had a poster of Franz Josef Strauß, the Barry Goldwater of German politics, above his teenage bed, was also impressed by the pageantry of George W. Bush’s ‘compassionate conservatism’, which he witnessed at close range as a CSU emissary to the 2004 Republican Convention in New York (Curiously, Armin Laschet introduced this fairly critical biography of Söder at an online event in Berlin the other day, partly, it seems, as a gambit to narrow the race for the Chancellorship down to the two of them.)

How did this immaculate CSU stalwart become, over the past year and a half, an ardent progressive, posing as Merkelite Landesvater? It is one of the puzzles of contemporary German politics. The answer has roots deeper than simply the fact that Söder, with his eye on Merkel’s job, now has some appreciation for how she does it. To begin with, it’s worth recalling how drastically both he and the current Interior Minister (and preceding Minister President and CSU chair) Horst Seehofer misread the consequences of Merkel’s 2015 decision to keep the German border open to asylum-seekers. In their interpretation of events, the political crisis over refugees was the uncorking of a bottle that would release all of the conservative spirits that Merkel had suppressed. As Merkel seemed to reveal her true colors – that of a delusional humanitarian – Söder and Seehofer finally thought they had her cornered. 2015–18 was the period in which they tried to finish her off by riding the wind of the right-wing backlash toward her and her policies (Needless to say, there was no principle in any of this: in his days as the Health Minister under Kohl, it was Seehofer who was regularly criticized within his own party for being ‘communist’ when it came to the destitute). Seeing no threat from the AfD, Seehofer and Söder decided to relax the CSU’s Strauß doctrine (‘Never allow a democratically legitimized party right of the CSU’) and appeared to think that the fledgling party’s promotion of more forthright Euroscepticism could be helpful. Then comes the CSU’s Austrian romance. Let us revisit those happy days:

- Mid-December 2017: The Austrian Chancellor, Sebastian Kurz of the ÖVP, and his coalition partner, Heinz-Christian Strache of the hard-right FPÖ, presented their coalition agenda withdrawing protections for refugees at the Kahlenberg, site of a decisive 1683 battle against the Turks.

- Early January 2018: Alexander Dobrindt, head of the CSU’s parliamentary group, published his call for a ‘Middle Class Conservative Turn’ in Die Welt (Springer’s ‘prestige’ paper). Portions of it read like a less erudite version of Anders Breivik’s manifesto.

- Early January 2018: Viktor Orbán was the guest of honor at the CSU-Klausur, and gave an interview to Bild-Zeitung (that had been leading a pro-Kurz campaign for weeks by then): ‘We are not talking of immigrants or refugees, we are talking about an invasion’.

And so the CSU with Söder in the driver’s seat appeared prepared to go down the Austrian road: EU-critical, Putin-curious, agrarian-traditional, culture-war-trigger-happy, maximally Islamophobic neoliberal.

Then came the stunning upset. The CSU was humiliated in the 2018 October regional election. Söder lost 10 percent of the vote, much of which seemed to have been recouped by the Greens, who offer an ever more urban and online electorate the sought-after credentials of anti-racism and cosmopolitanism. With 16 seats lost in the parliament, Söder’s majority vanished. He had to build a humiliating, if not unprecedented coalition with the Free Voters of Bavaria, a hodge-podge ‘non-ideological’ party of the centre. It was now clear that the turn to the right had been a mistake. How did Söder respond? By conducting one of the most dramatic U-Turns in recent German history. Overnight he became a lover of bees and trees – calling for new regulations for their protection. He declared combustion engines would be banned by 2030. His progressivism even overshot what his party was prepared to stomach. At the CSU conference last year, Söder’s proposal for a quota of 40 percent women at all levels of the CSU was rejected by the party delegates. The CSU still has the best discipline of any party in the land, but there are audible grumblings from lower quarters. The CSU Landtag chair Thomas Kreuzer has been lately appending pointed reminders about ‘the farmers’ to Söder loyalty oaths.

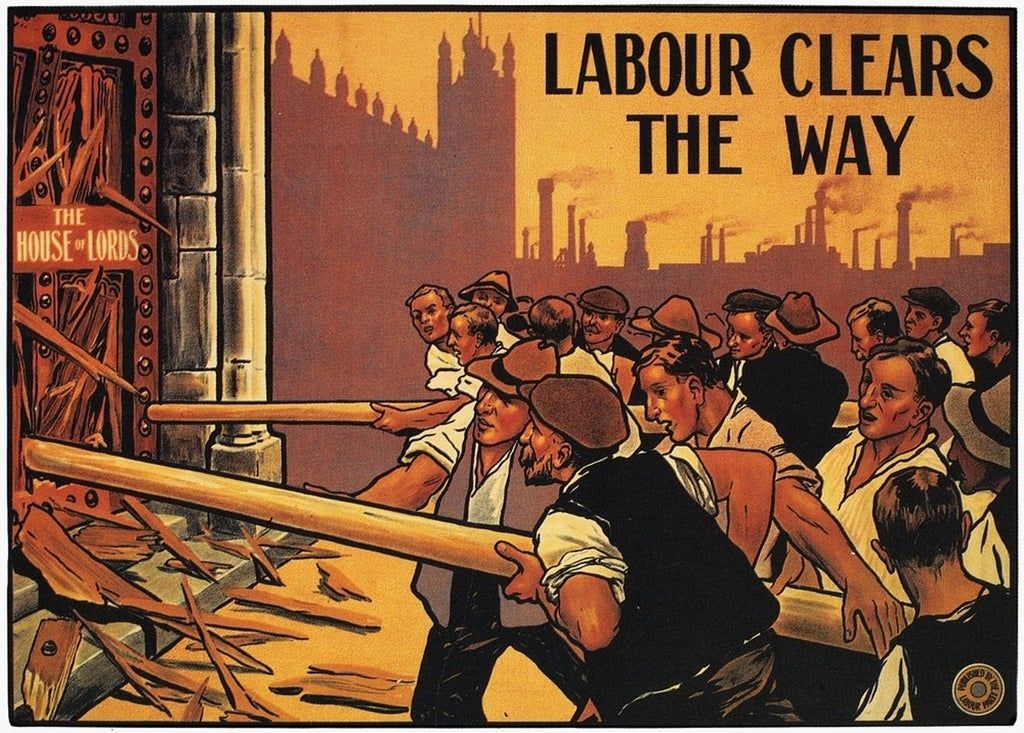

What all of this reveals is not simply that Söder is now, belatedly, reforming the CSU in the same way that Merkel did the CDU. It shows that, with his eye on the Chancellorship, Söder knows that he has no choice but to forge a working alliance between main sections of export-oriented industry and the progressive middle classes. He grasps the objective pressure Merkel is under to balance the hegemonic alliance of big multinational corporations (as opposed to smaller, more conservative family businesses), moderate conservatives and urban liberals. Urbanization and export-orientation are two of the dominant forces shaping German social life: and they are moving the country in a progressive and liberalizing direction. (The AfD, caught in factional infighting, and experiencing diminishing returns on its novelty, has meanwhile become a party of last resort for disenchanted members of the state security apparatus and the Bundeswehr). Söder knows that he must divert some of the Green vote or at least make the prospect of ruling with them more plausible. The Austrian example was always an unworkable fantasy in Germany, even in Bavaria, where there are fewer traditional Catholics, the population is urbanizing, and there is a strong ‘progressive’ neoliberal ideology that emanates from BMW (Munich), Siemens (Munich), Adidas (Herzogenaurach), Audi (Ingolstadt), etc. Companies like this do not exist on the same scale in Austria; the country is 20 percent less urban than Germany; and Austrians never underwent any comparable ‘Vergangenheitsbewältigung’, as they still prefer to think they were not responsible for crimes committed by Nazi-Germany. Despite Kurz’s relative popularity among the professional classes of Vienna, and his wing of ÖVP’s closer position to the Federation of Austrian Industries (Industriellenvereinigung), which represents big capital groups, Austrian conservatives can still cobble together a majority without the sort of urban progressives on whom Merkel has increasingly come to rely.

What are Söder’s chances for Chancellorship? It is still too early to say. He has acquired enemies all over the country, but also ardent supporters in unlikely places. As he approaches the seat of power in Berlin, he will come under much more scrutiny. It is practically a German political rite of passage at this point to plagiarize your doctoral dissertation, but if anything it’s a sign of Söder’s intelligence that he did not resort to the copy-paste method of his peers, but rather appears to have commissioned the thing wholesale, unless one is persuaded by the image of one of the busiest political operatives in the land pouring over hundreds of documents written in Kurrentschrift in a state archive to produce the 263-page thesis, ‘From old German legal traditions to a modern community edict: The development of municipal legislation in the Kingdom of Bavaria between 1802 and 1818’. That said, Söder has had a very good pandemic, which suited both his and the CSU’s authoritarian instincts. He locked Bavaria down faster, harder, and more coherently than any other state minister, and his resolute media performances played well in the liberal press. As he considers the dimensions of Merkel’s shoes, Söder is seeing like the German state: no longer the optics of the Mittelstand businessman or the farmer in the beer tent, but something more total and omniscient: Der ideelle Gesamtkapitalist.

Read on: Joachim Jachnow on the degeneration of the German Greens; Christine Buchholz’s wide-ranging survey of the political landscape under Merkel.